Is 'guerrilla war' being waged on news broadcasters?

- Published

How should the mainstream media tell the news in an increasingly fragmented world?

How should the BBC and other broadcasters respond to the changing media landscape including "guerrilla" attacks on social media? In an inaugural lecture, external to mark the contribution of the late Steve Hewlett to journalism, his friend and colleague Nick Robinson discusses the issue. Steve Hewlett, a BBC Radio 4 presenter and former Panorama editor, died this year from cancer. This is an edited version of that lecture.

News is too important to be reduced to a three-letter word.

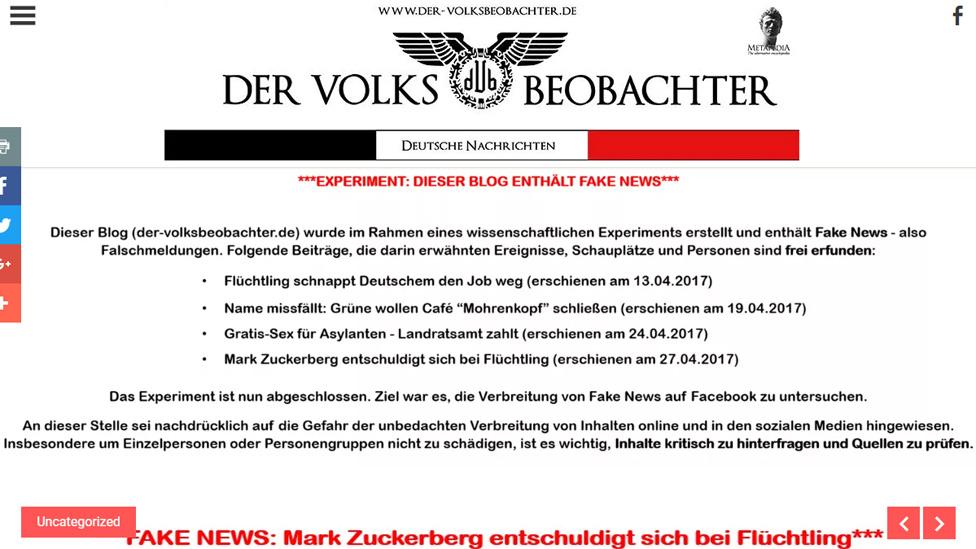

Yet that is a risk we now face as more and more people get their news from social media, with what they read and see determined for them by the all powerful algorithms that prioritise emotion - "OMG" or "LOL" - over facts and analysis.

The way in which people consume news and react to what broadcasters say is changing at huge speed, and we need to change with it.

According to BBC research, if you look at the way young audiences consume video content - that's everything from full-length programmes to clips on social media - only around a third of 16 to 24-year-olds' "viewing occasions" involve live TV programmes watched on what their Mums and Dads would call the telly or "the box" (rising to 40% if you include live streaming TV.) Just three years ago, this figure was more than half.

According to Reuters Digital News Report, external, a growing number of people access news on their smartphones, almost a half while in bed, a little fewer on the bus or train, and a third on the toilet.

The same report suggests trust in UK media is down by 7%, way ahead of the United States but behind other European countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Poland and many others.

To summarise, let me quote one of the bosses of one of those corporate giants who pose the greatest challenge to the old ways of doing things, Google News's Richard Gingras, whom I met in Silicon Valley a few weeks ago.

Information v affirmation

"We came from an era of dominant news organisations, often perceived as oracles of fact," he told me.

"We've moved to a marketplace where quality journalism competes on an equal footing with raucous opinion, passionate advocacy, and the masquerading expression of variously motivated bad actors."

Facebook is the most popular social media and messaging service for news engagement across the world

Mr Gingras points out what is, perhaps, the key challenge posed by social media: "Affirmation is more satisfying than information - always has been."

But it's worth noting that BBC News is still watched, listened to and read by a remarkable number of people.

And we are trusted, even by the young, who come to the BBC when it matters. For example, 91% of under-34s consumed the BBC's 2017 general election coverage in the week of the vote.

But trust as a whole is declining because of two main factors:

the increased polarisation of our society and our national debate

the increased use - particularly by the most committed and most partisan - of social media and alternatives to what they call "MSM" - the mainstream media

Those who have seen themselves as fighting the establishment - whether Scottish Nationalists or Ukippers, Corbynites or Greens, backers of Leave pre-referendum but, since the vote, backers of Remain - have not just complained about the MSM.

Many have also established their own alternative media sites.

Guerrilla war

Campaigners on the left as well as the right have been looking, listening and learning from what has happened across the pond.

They know that there is method behind what some regard as the madness of attacks by President Donald Trump - often via Twitter - on the "failing" press as purveyors of "fake news".

Attacks on the media are no longer a lazy clap line delivered to a party conference to the raise the morale of a crowd of the party faithful. They are part of a guerrilla war being fought on social media, day after day and hour after hour.

How to respond? I turn to my late friend Steve Hewlett here for inspiration.

Steve became best known for telling the story of the end of his life as he faced cancer, but throughout his career as a journalist - whether as editor of the BBC's Panorama programme or presenter of BBC Radio 4's The Media Show - Steve told stories about the world we live.

What made him different is that he asked questions many others failed to ask.

'Probe the consensus'

In the early days of Channel 4, Steve worked on a series called Diverse Reports, which had a clearly defined purpose: "Wherever you can find the liberal consensus, probe it, probe it, probe it. And if there's another way of looking at it, broadcast it."

The Royal Television Society has launched the Steve Hewlett scholarship for young journalists

It was the only programme I've heard of that examined the case for restoring capital punishment.

My instinct is that we should build this mindset into all our programmes, so that we ask questions - and can share online items that ask questions - that are invariably not asked.

Again and again over the years, views that start off being seen as extreme quickly become the new conventional wisdom - monetarism, green politics, gay rights, calls for curbs on immigration.

Indeed, Jeremy Corbyn's unexpected political rise shows that the conventional wisdom is there to be proved wrong.

It has become fashionable to argue that the media failed to spot political movements such as Corbynism, the desire for Brexit or the rise of Donald Trump because journalists are "too far removed" from those whom they report on, and I'm pleased the BBC is looking at examining the backgrounds of those it employs.

When I first met Steve, it was on the BBC's Brass Tacks, a current affairs programme based in Manchester.

The team included a former merchant seaman with a broad scouse accent and arms covered in tattoos. I have worked with few like him in TV since.

Diversity of thought

The RTS scholarship set up in Steve's memory should be a useful step to finding more like him.

But Ofcom's chief executive, Sharon White, is right to say that on-air diversity should bring with it diversity of thinking.

Ofcom's Sharon White has warned broadcasters they are failing to represent society

Research suggests people who don't trust the media often think they don't hear the views of "people like me".

They should indeed hear themselves reflected, but we should also confidently tell them that they will hear people with whom they'll disagree.

We must learn from our past, when the BBC has been slow to challenge the conventional wisdom of the day. Churchill's pre-War warnings about the dangers of German rearmament were heard by radio listeners not in his own country, but in the US.

The way Churchill was handled is a powerful warning of the dangers of the BBC believing it is being balanced by silencing the voices of those who do not represent conventional wisdom.

Impartiality

It is an answer to all those who complain that former BNP leader Nick Griffin should never have been invited on to the BBC's Question Time programme, to those Brexiteers who fill my Twitter timeline with demands that we should not interview "that failed leader" Nick Clegg, the Remainers who say the same about Nigel Farage, and those who argue that Nigel Lawson should never be interviewed about climate change.

The Green Party and leading scientists recently criticised the BBC for interviewing the climate change sceptic Lord Lawson

There is a danger in these times that a growing number will question whether impartiality still has any real meaning, whether it is an establishment plot to limit debate and whether it can be sustained in an era of almost infinite media choice.

I believe that it is still vital, and we should proudly tell our audience that the BBC is not owned, run or controlled by the government, media tycoons, profit-seeking businesses or those pursuing a political or partisan agenda.

It is staffed by people who - regardless of their personal background or private views - are committed to getting as close to the truth as they can, and to offering their audience a free, open and broad debate about the issues confronting the country.

They aim to deliver what Carl Bernstein called "the best obtainable version of the truth".

We don't always get it right, and should quickly and openly admit it when we don't.

But news is much, much more important than those ubiquitous three-letter words allow.

This is an edited version of Nick Robinson's inaugural Steve Hewlett Memorial Lecture, to be delivered on Thursday, 28 September. The BBC Radio 4 presenter and former Panorama editor Steve Hewlett died in February from cancer, aged 58. He discussed his diagnosis and treatment in a series of frank and moving interviews with the BBC Radio 4 PM programme's Eddie Mair.

- Published22 September 2017

- Published23 August 2017

- Published3 August 2017

- Published1 August 2017

- Published22 June 2017