'I gave up my job to fight Brexit'

- Published

Would you give up a job you loved to fight for a cause that you knew, in your heart of hearts, was probably lost?

That's what Mike Roberts did and he is not alone.

Mr Roberts was a chief inspector with Greater Manchester Police but took early retirement to campaign to keep Britain in the European Union.

"I was so frustrated with the Brexit process," he says, "I had the idea of starting a political party, like Mr Farage did all those years ago, with a very simple message and a very simple brand."

Nigel Farage, of course, ended up as leader of the UK Independence Party, or UKIP. Mike Roberts came up with UKRemainEU. He briefly considered changing his surname to that but, perhaps wisely, decided against it and registered the name as a political party instead.

The police take a dim view of their officers taking part in political campaigns, so having racked up 30 years with the force, he decided to quit to devote his time to the anti-Brexit cause. As a senior officer he could have carried on working, but he says couldn't stay neutral any longer.

"What really fired me up was when I went on holiday to Holland just after the Brexit vote and my five-year-old son said he would like to live there when he grows up. I said 'you might not be able to because of Brexit'."

At the moment, UKremainEU is little more than a twitter feed but Mr Roberts wants to hook up with like-minded individuals to stand under his party's banner in upcoming elections.

"In every area there will be somebody like me," he says.

How the UK voted in June 2016

Leave polled the most strongly in 270 counting areas, with Remain coming first in 129.

our browser does not support this interactive content. Results in detail are available here.

Britain is on course to leave the European Union on 29 March, 2019 - but even though both Labour and the Conservatives are committed to making Brexit happen on that date, Mr Roberts believes it can still be stopped, because he thinks Britain is unlikely to agree an exit deal by then.

"I want to be ready and waiting when it all falls apart," he says.

But he is realistic about his chances. Starting a successful political party from scratch in the UK is about as likely as winning the lottery.

"I am probably on a right loser but I want to be able to say to my children I did everything I could - even registering my own party - so I can look myself in the mirror and say I tried to stand up for the values of this country."

Role models? How UKIP got started

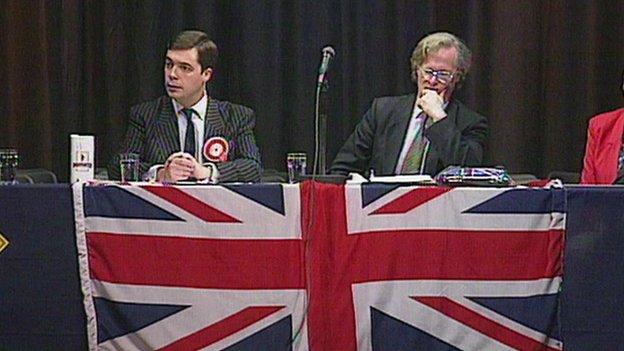

Nigel Farage, pictured at a UKIP event in 1997

UKIP began in the early 1990s as a tiny band of disaffected Conservatives and others alarmed at the prospect of Britain becoming part of a European "super state".

It was initially called the Anti-Federalist League - founder, history lecturer Alan Sked, got 117 votes in the 1992 general election in Bath. A change to a more voter-friendly name, the UK Independence Party, helped them grab 150,251 votes at the 1994 European elections, still only 1% of the total vote.

Nigel Farage, standing for UKIP on the same day in the Eastleigh by-election, had a close run thing with the Monster Raving Loony candidate, eventually beating him by 169 votes. Within five years Mr Farage was a member of the European Parliament.

By the 2014 European elections UKIP got a table-topping 4.4 million votes and their popularity led to David Cameron to decide to promise an In-Out referendum ahead of the 2015 general election.

Other anti-EU parties have come and gone over the years, with some such as the English Democrats, briefly looking like they could become contenders.

Chris Coghlan is another public servant who felt he could not sit on his hands while the country took what he believed to be a disastrous turn.

Chris Coghlan: "There is huge frustration out there"

A former counter-terrorism officer and diplomat, he quit his job earlier this year to join the Brexit "resistance".

"I am taking a big risk for my ideals," he says, but adds: "There are several groups out there and I think that is pretty healthy because it shows we are on to something."

Like Mike Roberts, he dreams of doing "a UKIP in reverse", piling pressure on sitting MPs who he believes have sold out their pro-European principles for the sake of their careers.

The 36-year-old stood in June's general election in his home patch of Battersea, in South London, as an independent anti-Brexit candidate, gaining 2% of the vote (Labour ended up taking the seat from the Conservatives with a huge swing, one of the surprise results on election night).

But he is also looking beyond Brexit. He aims to "transform" British politics with a new centrist party, Renew, that will marry equality of opportunity with support for free markets. He says the new party has financial backing and has already signed up about 100 potential candidates.

"I don't think either of the two main parties are credible right now," says Mr Coghlan, who has been a member of both Labour and the Conservatives in his time (he tore up his Tory membership over the EU referendum).

"People think if you want to create change it has got to be through the major parties - I don't think that's the case any more.

"There is huge frustration out there and I think that needs to be expressed."

Not every anti-Brexit campaigner has been willing, or able, to give up the day job.

Journalist Jeremy Cliffe caused a minor stir on social media last month when he sent out a series of tweets announcing his plan to start a new party, the Radicals.

Jeremy Cliffe: "Accidentally" founded a party on twitter

The policy programme was indeed radical: stopping Brexit, joining the euro, and making a Brit - perhaps Conservative Europhile Ken Clarke - the next President of the European Commission.

He said he was inundated with emails of support, though some pointed out it was odd for a "pro-EU, pro-tech" party not to have a more sophisticated system of registration than an email address.

He set up a website for the party and Ladbrokes offered 500/1 odds on him being the next prime minister.

But just 14 hours after his first tweet, he said "taking this forward would not be compatible with my job as Berlin Bureau Chief for The Economist… I am arranging to hand it over to a committee in Britain that might, if it opts to do so, advance the Radicals to a next stage".

According to an email leaked to Buzzfeed, external, the Economist told staff that Mr Cliffe had "accidentally started a political movement", and urged the magazine's journalists not to endorse it.

Starting a new political party is, in many ways, the last resort for people who feel their views are being ignored at Westminster. There are plenty being formed - here's a list of those registered in the past three months:

It can be a long, lonely road, ending all too often in the early hours of the morning in a draughty sports centre with the humiliation of getting fewer votes than a man dressed as a fish finger or some other novelty candidate.

It used to be mainly anti-European parties, with names like Britannica or the British Independents, and logos depicting a British lion or a union flag, that took on the challenge. Such groups are still being formed, if the Electoral Commission register of new parties is any guide, external.

It will be interesting to see whether the parties springing up from the fledgling anti-Brexit movement will have the same staying power as their Eurosceptic rivals. Seventeen months on from the EU referendum, there is no clear evidence of a major shift in opinion, external.

So it could be a long haul.