Brexit bill: Will we ever know a precise figure?

- Published

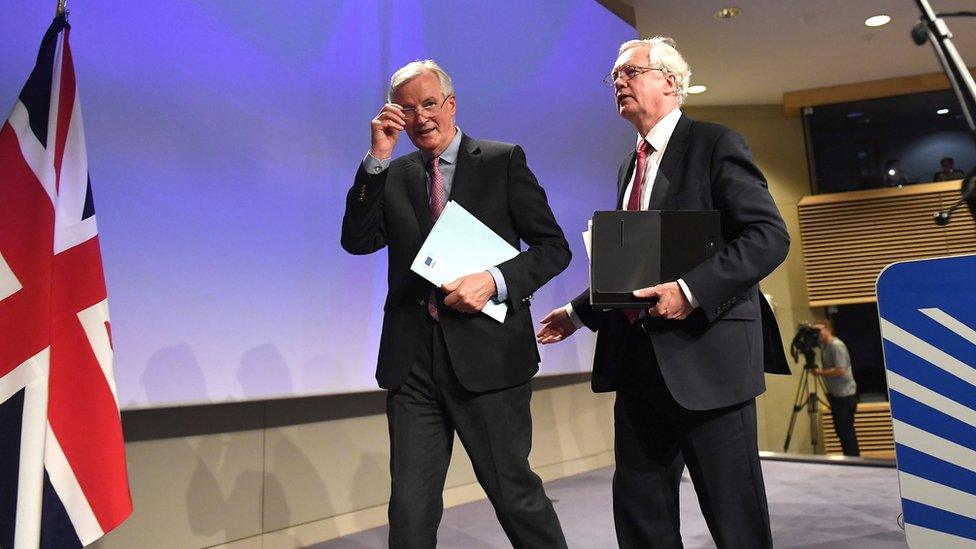

Have they agreed a figure?

No, and nor do they want to in public - on either side - because everyone knows how politically sensitive a precise number is.

The aim has always been to agree on the way the bill will be calculated.

In her speech in Florence in September, Prime Minister Theresa May said the UK would honour the financial commitments it had made as a member of the European Union.

The EU has been seeking reassurance that the UK means "all" its commitments as the EU defines them, and this has been the focus of the most recent negotiations.

A backroom agreement on the broad outlines of a deal may now have been reached, but it still needs to be formally discussed and agreed at the political level.

If they have agreed in theory on a method, why do the estimates for the bill vary so widely?

Because there could still be plenty of technical haggling to come about the detail.

At the moment, estimates for the bill range between 40bn and 55bn euros net, although Downing Street has played down anything above 50bn.

Expect various numbers to be produced, but don't forget that the process isn't over yet.

A deal now would certainly be a breakthrough, but in practice it just means everyone agrees "sufficient progress" has been made.

Internal EU documents foresee the "finalisation of negotiations" on phase-one issues (including the financial settlement) continuing until October 2018.

The biggest single chunk of any bill will arise from the UK's share of budget commitments that have been made but not yet paid out - known in EU jargon as the Reste a Liquider (RAL).

The RAL for the whole of the EU is currently valued at about 238bn euros, and that could rise to 250bn euros by the time the UK is due to leave.

But there are various ways of calculating exactly what the UK share of the RAL should be.

How might it be calculated?

The amount any country pays into the EU budget every year depends on the size of its economy relative to the EU economy as a whole. It is calculated by working out gross national income in euros.

To calculate the Brexit financial settlement, the EU has proposed taking an average of the British budget contribution over a five-year period, from 2014 to 2018 (the five years before the UK leaves), which produces a UK share of just under 13%.

UK officials think they can reduce that percentage.

They would, for example, like to include the years 2019 and 2020 in the calculation - because those years form part of the EU's current seven-year budget and the intention is that the UK will still be making budget contributions, as part of a transition arrangement, in 2019 and 2020.

Using a seven-year calculation would help reduce the UK bill because the decline in the value of sterling since the referendum means that the size of the UK economy in euros has got smaller.

The UK and the EU may have broadly agreed how to calculate a bill - but the exact size of that bill is still to be determined.

Are there other ways to chip away at this part of the bill?

Potentially, yes. In 2015, the UK had to pay a one-off budget surcharge of 2.1bn euros, which dealt with past payments. The UK argues this payment should not be included when calculating the average British budget contribution.

Agreeing the average proportion of the EU budget paid for by the UK will be key. If the UK share was reduced from about 13% to about 12%, that could cut the RAL bill by roughly 2.5bn euros.

There is also a debate to be had about what are known as "decommitments" - some of the money the EU has committed to spend in budgets will end up never being spent.

That's because many big infrastructure projects in Eastern Europe, for example, have to be co-financed by national governments, and some of them lack the capacity to spend the money they have been offered.

The UK wants the Brexit bill calculation to include a higher "decommitment" rate than the EU has so far suggested.

What about pensions?

This is another big part of the current negotiations.

The estimated financial liability for the EU's pension and sickness-insurance schemes - those that cover the EU's employees - was about 67bn euros at the end of 2016.

But this figure is based on an interest rate - the euro area discount rate - of 0.3%, which is a historically low level.

Taking an average of the discount rate over a much longer period - say 20 years - would produce a much higher interest rate, and a much lower estimated pension liability.

That would reduce the UK contribution significantly, and could reduce the overall bill by another few billion euros.

And there's also the timescale?

Yes, a 25-year-old EU employee may not expect to receive their pension for another 40 years. What might the discount rate be in 40 years' time? No-one knows.

But it is possible that the UK could make small pension contributions for decades to come, which would:

help spread the load

make it all but impossible for anyone to calculate a final figure for the Brexit financial settlement

Other liabilities could also be paid out over time rather than as a lump sum.

Some of the money committed but not yet paid in annual budgets will not be handed out for several years.

If the UK agrees to honour commitments due to be made in 2019 and 2020 (after Brexit but potentially during a transition) some of that money may not be paid out until 2024 or 2025.

The EU - including the UK - agreed to pay about half the cost of upgrading the A1 in Poland. The road may not open until after the UK leaves the EU

What about a UK share of EU assets?

This is also a matter for negotiation. It's difficult to take a share of fixed assets such as buildings - the argument is that these assets belong to the EU as a whole rather than to the individual member states collectively, and no country had to pay money into the budget to take a share of these fixed assets when they joined the EU.

But there are also cash assets, generated from things such as big fines imposed on companies. The UK would like a share of that money to be taken into account in the overall calculation. A row could be looming though about the future of the 3.5bn euros of UK capital at the European Investment Bank.

We're never going to know how big the bill is then?

It's extremely unlikely. But if the starting point for the EU was a net figure of about 60bn euros net, and the starting point for some Brexiteers in the UK was zero… well, the end result is going to be a lot closer to 60bn than to zero.

The government has always accepted that there were bills to be paid - but it wants to focus on a much bigger prize, the future trading relationship and the overall health of the UK's £2.2tn economy.

- Published29 November 2017

- Published28 November 2017

- Published28 November 2017

- Published11 July 2017