Brexit: Guidelines for the next stage of talks

- Published

The European Council has said that Brexit talks can enter the second phase following last week's agreement.

As a result it has published its guidelines, external for the next stage of talks.

Here are some of the key phrases from that document.

Don't forget that there are plenty of crucial details that still need to be resolved before negotiations on a withdrawal agreement come to an end.

That means the financial settlement, citizens' rights and of course, the Irish border.

Sufficient progress is not the end of the story, but the text also makes it clear that there will be a concerted effort to lock in what has been agreed so far - and that if the EU detects any reluctance or backsliding from the UK then that will have a negative effect on discussions about the future.

Theresa May has already agreed that a transition of about two years will take place under existing EU rules and regulations, but the EU's text makes crystal clear what it believes that means.

The UK will have to accept all EU law (that's what the acquis means) including new laws passed during the transition itself.

But it will no longer have a seat at the table when those laws are made. To put it brutally - the UK will, for a while, become a rule-taker rather than a rule-maker.

Both sides talk of a strictly time-limited transition period, so there doesn't appear to be much appetite at the moment for extending it.

Quite what happens if a future trade deal isn't ready by the end of the transition, a scenario many experts think is quite possible, will have to be debated in the future.

During the transition, the UK will have to accept the full jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, and all four freedoms - including the freedom of movement of people.

The EU says the UK will remain in the single market and the customs union during a transition, while the UK insists that it will leave both on Brexit day.

This could become a semantic argument, because by accepting all rules and regulations - in other words, the status quo - the UK will remain in the single market and the customs union whether it likes it or not.

The British government has suggested that some things - like dispute resolution mechanisms - could change during the transition as agreement is made on future co-operation. But there's little appetite in the EU for that - in its view, you're either in or you're out.

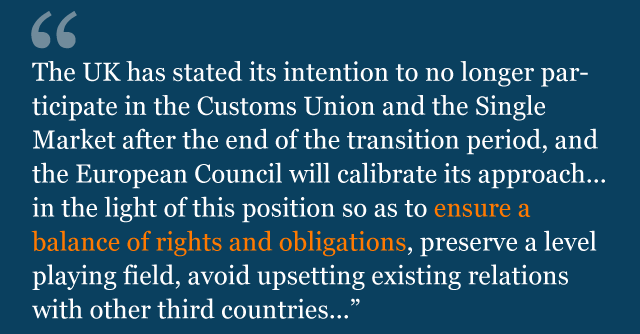

The EU 27 stress that they want a close partnership with the UK in the future, but here they are setting out the limits of what they could mean.

The further away the UK wants to be from the rules and regulations of the single market the less access it will have - there is no such thing as partial membership.

This gets us back to the unresolved debate about what "full alignment" at the Irish border really means in practice.

The phrase "preserve a level playing field" is important too. The EU is anxious to ensure that the UK doesn't try to undercut the EU in any way by having looser regulations in certain key areas, and, if it does, then there will be consequences.

EU negotiators won't have the authority to start discussions with the UK on future relations (including trade and also things like security and foreign policy) until another set of guidelines is adopted in March 2018.

That gives the two sides not much more than six months to agree the text of a broad political declaration on the outlines of the future relationship.

The EU hopes to get that finalised by October 2018, but it emphasises that formal trade negotiations can only begin after the UK has left the EU.

Informal contacts on what the future might look like are probably taking place already, but the EU is still waiting for greater clarity from London about what exactly the UK government hopes to achieve in the long term.

The UK is trying to be as ambitious as possible about what can be done before Brexit actually happens. The EU, though, emphasises that trade talks will have to continue long after the UK has left.

- Published15 December 2017

- Published15 December 2017