Senior clerk: bullying is 'unresolved' issue in Commons

- Published

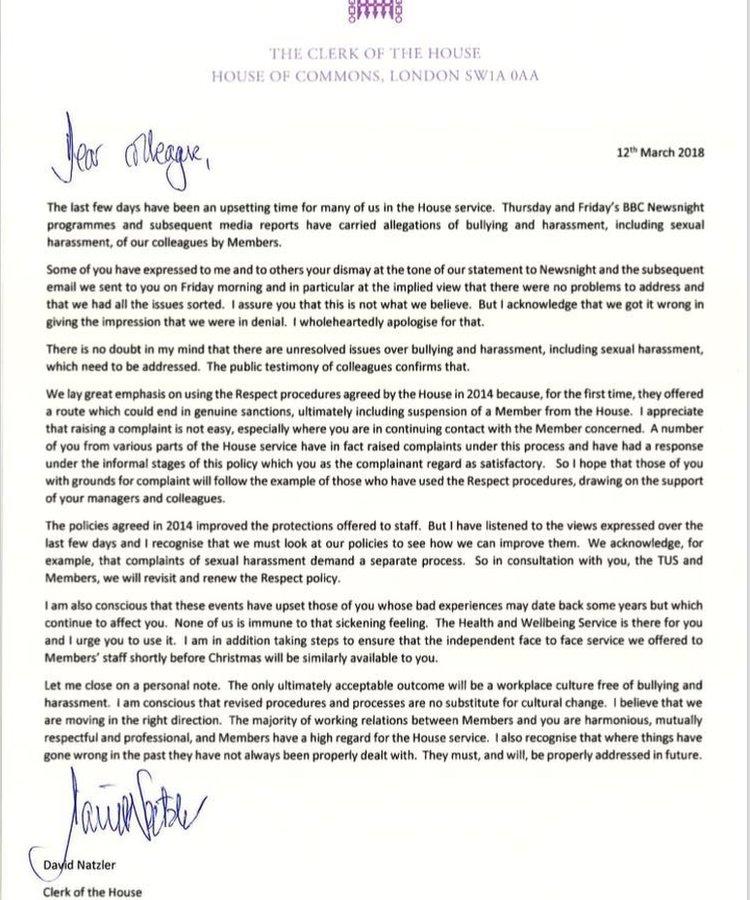

"There is no doubt in my mind there are unresolved issues over bullying and harassment, which needs to be addressed. The public testimony of colleagues confirms that." That's what David Natzler, the clerk of the House of Commons, wrote to members of the House of Commons Service today.

Last Thursday, Lucinda Day and I reported on a major problem for the House of Commons Service - the non-partisan officials who run the house. We published accounts of MPs harassing and abusing members of this service, the group usually known as the "clerks", and the lack of appropriate action.

Last week, the House of Commons authorities were not sympathetic: one serving clerk's description of a "culture of fear" about reporting bullying and harassment by MPs was dismissed as a "grotesque exaggeration".

This morning, Mr Natzler, the head clerk, changed his tone: "Some of you have expressed to me and to others your dismay at the tone of our statement to Newsnight and the subsequent email we sent to you on Friday morning."

"I acknowledge we got it wrong in giving the impression we were in denial."

There has been quite the shift. He also noted: "The policies agreed in 2014 improved the protections offered to staff. But I have listened to the views expressed over the last few days and I recognise that we must look at our policies to see how we can improve them."

It is worth taking a moment to look at those protections, because the 2014 "Respect Policy" is unusual. This document, introduced after the failure of the 2011 Respect Policy, which we documented last week, is supposed to protect the clerks from inappropriate behaviour by MPs. A lot of clerks - including, now, the head clerk - think it is not good enough.

Letter from David Natzler, Clerk of the House of Commons

The Respect Policy

The 2014 Respect policy starts with proposing a sequence of informal measures for dealing with bullying and harassment - "raising the issue with the person concerned and asking them to amend their behaviour towards you". Then, it proposes mediation, if both sides agree ("The mediator does not take sides or tell the parties what to do, nor do they make judgements about right or wrong").

If that is inappropriate, staff can raise a grievance, which will be adjudicated by a senior officer. But this process is very weak: "an apology where appropriate" is the only sanction it discusses. To get a serious response, such as suspension of an MP, staff must escalate the process to the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards - but it is not wholly clear how many cases she might ever actually hear.

The Commissioner may only take on a case where the MP has behaved in such a way as to "cause significant damage to the reputation and integrity of the House as a whole or of its Members generally". It is worth considering the idea of an incident so serious that it would "cause significant damage to the reputation and integrity of the House".

Would "ordinary" workplace bullying or harassment - the sort of thing which must be tackled in every large workplace - meet that definition? The policy also states "the Commissioner's decision is final and there is no appeal process". For a large range of malfeasance that would lead to sacking elsewhere, a private letter of apology may be the only sanction available.

If the complaint were to be heard and then upheld by the Commissioner, a memo on the case would be passed to the Committee on Standards which will "decide on the appropriate course of action". The Committee on Standards has non-MP members - this may be an improvement on the predecessor policy, where it was MPs who judged these cases. The committee also has the power to suspend MPs.

But MPs still have half of the places on the committee, and it does not have a reputation as the scourge of parliamentarians. The policy is also quite clear that: "no further internal action in relation to the Member will be possible or appropriate following consideration by the Committee or the House." Clerks have one shot to deal with problematic MPs.

Clerks have a lot to fear here: the bar for getting a case heard is high - although it is not clear how high. If they cannot meet that requirement, all they may get is a letter. In return for that, they will have angered an MP. The whole process is also confidential, right up until the end, when the Committee on Standards will announce its decisions: that may make patterns of behaviour hard to demonstrate.

A lot of this policy remains hypothetical and untested: in January, we asked the House of Commons, under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act, how many cases had been escalated. They replied: "Of the 16 Respect cases managed under the current policy, all of these were resolved without mediation, and none were referred to the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards."

The clerks are showing they do not trust the system by declining to use it

- Published9 March 2018

- Published8 March 2018