Obituary: Baroness Trumpington

- Published

Baroness Trumpington: From Bletchley Park to the House of Lords

She was the society girl and war-time Nazi codebreaker who fended off the amorous advances of Lloyd-George.

In a long political career, she was mayor of Cambridge, a Conservative whip and served as a health minister in Margaret Thatcher's government.

But Baroness Trumpington, who has died at the age of 96, found fame and a place in the nation's heart late in life - flicking a V-sign at a colleague during a House of Lords debate. It was arguably the best career move she ever made and she revelled in her newfound YouTube notoriety.

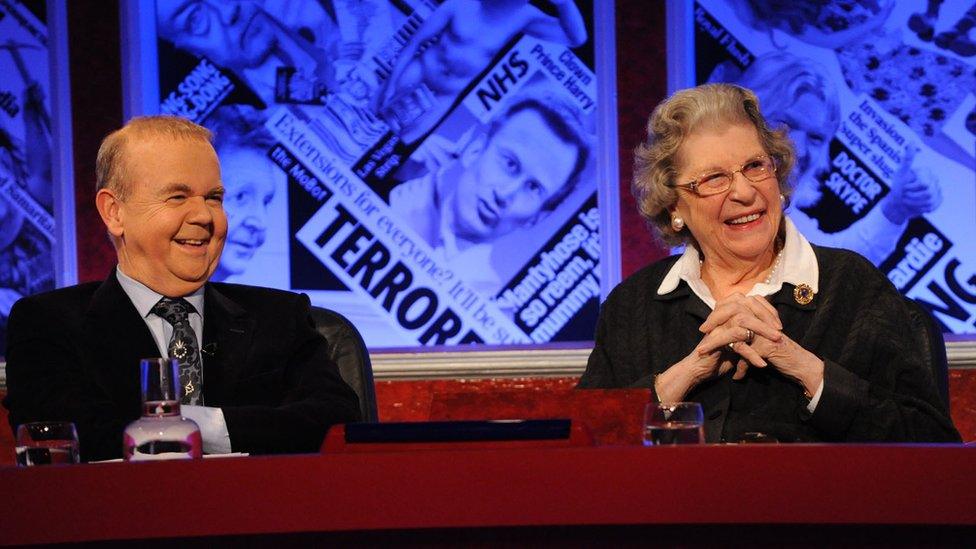

She went from strength to strength, appearing as a no-nonsense panellist on TV programmes like Have I Got News For You - mocking the BBC for requiring her to sign a form to say she was not pregnant in her 90s.

She attended debates in the Lords every day until her retirement from public life in 2017, at the age of 95.

Even then, she found time to publish her life story, Coming Up Trumps, although she would shyly dismiss the ghost-written memoire.

"I don't understand what all the fuss is about," she told one reviewer. "I didn't write the damn book and haven't read it either."

Lady Trumpington worked as a war-time land-girl on the farm owned by former PM, David Lloyd George

Society girl

Jean Alys Campbell-Harris was born on 28 October 1922. Her father, Arthur, was a major in the Bengal Lancers and had served as an aide-de-camp to the viceroy of India. Her mother, Doris, was heiress to the fortune of a Chicago paint manufacturer.

The family was brought up in London in considerable privilege. Her parents moved in a fast set which included the then Prince of Wales, later the Duke of Windsor, and future wife, Wallis Simpson.

An army of servants attended to their every need at their huge house in Cumberland Place. But her parents lost everything when her mother's fortune was wiped out in the 1929 Wall Street Crash.

Her parents were forced to downsize and move to rural Kent and a house with no heating or electricity. The servants were let go with one boy hired to clean the gas lamps.

Jean's playboy father joined his step-father's paint company and worked his way up from the bottom. Her mother pulled in society favours and became a successful interior decorator, roaring between jobs on her pre-WW1 motorbike.

Their income meant their reduced circumstances fell short of penury. "We used to say my mother's idea of being poor was going to the Ritz on the bus," she recalled.

It was not a happy childhood. Jean was a "daddy's girl" but he wasn't around much. The nannies gave her little affection and, later, boarding school was miserable.

She was neither academic nor hearty which meant the other girls disliked her.

"They had crushes on each other and on the games mistress," she told one interviewer. "I used to go with the local boys to the woods and smoke."

The young Jean was developing an independent spirit that would characterise the rest of her life.

Fending off Lloyd-George

She left school at 15 having never sat an exam but fluent in French, German and Italian. She was good enough at tennis to consider junior Wimbledon but ended up being sent to an equally miserable finishing school in France.

As war broke out her parents wondered what to do with her. The answer was found on a farm owned by the family of the former prime minister, David Lloyd-George, in Surrey.

Jean worked as a land-girl and lived, on-site, in a small bungalow alongside Lloyd-George's much younger mistress, and later his wife, Frances Stevenson.

The famously priapic politician - who Jean would always describe as the "old goat" - would find reasons to stand her against a wall and measure her with a tape.

"I suppose that was the nearest to flesh he could get with Miss Stevenson's beady eye on him," she told the Guardian.

Baroness Trumpington startles Lord King during a debate in 2011

Bletchley Park

In 1940, her facility with languages changed her life. Then 18, she joined the team cracking Nazi codes at ultra-secret Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire.

She worked as a cypher clerk, transcribing messages from German submarines for Alan Turing's codebreakers who worked in complete isolation and with whom they never mixed.

The work was "deeply tedious" but at weekends she had a ball. She would hitchhike to London to stay with her friend, the newspaper proprietor and Cabinet minister, Lord Beaverbrook. Her stentorian voice meant her lifts wisely kept their hands to themselves.

Jean would meet friends at the Ritz and Claridge's which were legally required to serve meals for five shillings during wartime. "We would throw bread at each other and sing and behave so badly," she would reminisce.

She was so well-known at the legendary French restaurant, the Bagatelle, that the band would strike up a special tune as soon as she entered the building.

The lifestyle was fun but risky. After one society ball in 1941, she arrived at the Cafe de Paris nightclub in London's West End moments after it was hit by two Luftwaffe bombs. Thirty-four people were killed and dozens more injured.

New York

After the war she was determined to discover her mother's homeland for herself. She went to America on the Mauretania with £4 in her pocket.

Her brother got her a job in an advertising firm on Rockefeller Plaza but it was weeks until she was paid. She survived on the crisps she found at society parties and by rummaging in the bins behind nightclubs.

Jean loved the lifestyle. The war was over and she was an in-demand party guest famous for dancing on tables. She fell in love for the first time, to a man she would describe in her memoire only as "The American".

She would, undoubtedly, have stayed but for the chance meeting with the historian and Eton schoolmaster, Alan Barker. He had been wounded in Normandy at D-Day and had lost an eye at Monte Casino. "He was cosy," she said. "We just gelled."

When she travelled home to Britain for the Queen's coronation in 1953 he proposed. She followed him to Cambridge where he had become headmaster of The Leys. Their son, Adam, was born a year later.

The life of a provincial school-teacher's wife suited her. She adored entertaining the boys to tea. She had not, however, lost her old rebelliousness. She smoked, drank, jumped into swimming pools fully clothed and dancing around in a bathing costume to make the students smile for the school photo.

Lady Trumpington (centre) with fellow peers including Lord Grade (top), Lady Lawrence (second from right) and Lord Howe (right)

Politics

Outside school, she partied at Cliveden with the Astors and kept active in Cambridge as a local magistrate.

On one notorious occasion, she had to leave the bench when the serial violent rapist brought before her turned out to be her vegetable delivery man.

She was elected as a local councillor in the early 1960s and served as the city's mayor in 1971-72. Her husband could often be jealous of playing second fiddle on ceremonial occasions so "I decided not to make him mayoress as I thought that would make that worse".

When, in 1982, Barker suffered a stroke it was her work that kept her sane. He died a few years later.

She sought election to Parliament but was unsuccessful. Instead, she threw herself into public service in prisons and as UK representative to the UN Commission on the Status of Women.

Her connections with the Conservative leadership eventually saw her appointed to the House of Lords. She was great friends with Willie Whitelaw and, more importantly, one of the few women who could get on with Margaret Thatcher.

Her relations with the prime minister were warm and she claimed this was because she was not afraid to stand up to her.

"We got on terribly well. She was very good to me. I owe her everything. I went on the basis that I would be true to myself, say exactly what I felt, and if I got the sack, so what?"

Baroness Trumpington at the Lords and Commons Pipe and Cigar Smokers" Club annual luncheon in 2006. The former health minister attended the gathering which was held on no-smoking day

She became minister for health in 1985 although she refused to give up her passion for smoking. John Major kept her on at Agriculture during his administration and she served as baroness-in-waiting to the Queen, which mainly involved meeting foreign dignitaries at airports.

Her affection for the Lords ran deep. Politically, she was a traditionalist - resisting change to the Upper House, campaigning against "soft" treatment of criminals and voting against the ban on foxhunting.

And, on that famous occasion, gave her colleague Lord King a V-sign when he had the temerity to mention her advancing age during a Remembrance Day debate.

Celebrity

The incident made Lady Trumpington a late-life media personality. She was invited onto Desert Island Discs where she chose the crown jewels as her luxury in order to maximise her chances of rescue.

Lady Trumpington was the oldest guest ever to appear on 'Have I Got News For You'. She made fellow panellists laugh when she spoke about smoking cigars after sex

At 90, she became the oldest ever panellist on BBC1's Have I Got News For You although she turned down the offer of a repeat appearance when Margaret Thatcher died because she did not want to poke fun at her political hero and mentor.

To the end, Trumpers remained forthright and self-deprecating - putting much of her success down to blind luck. She also stayed equally determined to enjoy life to the full.

"I had a fantastic time during the war, doing a job that was very worthwhile, having fun when I went out on the town in the little time off that we were allowed and living life to the full whenever I got the chance.

"And I still certainly do."

- Published27 November 2018