Political heroes: Emily Thornberry on Barbara Castle

- Published

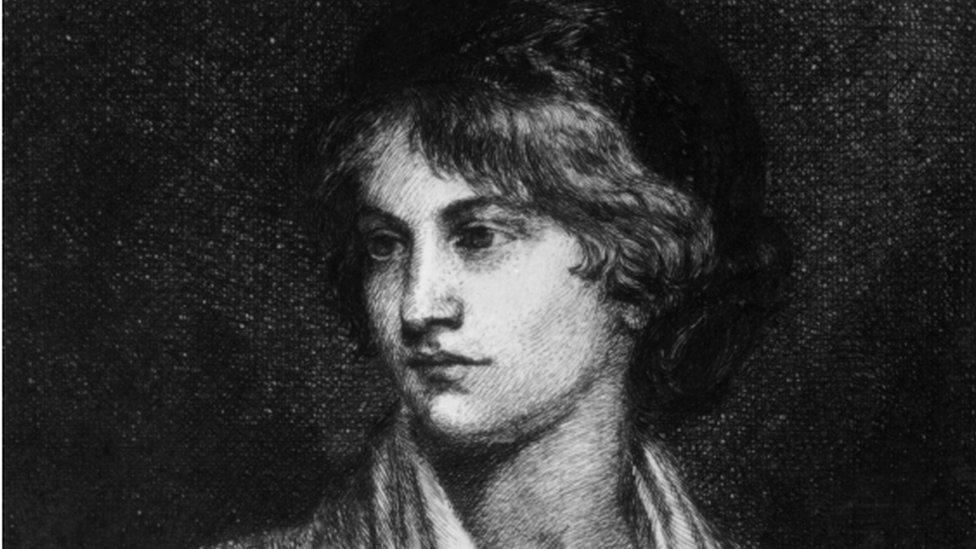

Barbara Castle role in UK politics and Labour history

Emily Thornberry did not have to think long about her choice of political hero, Dame Barbara Castle was on a list of one.

But what did cause some consternation for the shadow foreign secretary was when, the night before our interview, she mentioned her choice to her 24-year-old daughter, who had never heard of Dame Barbara.

Her mother was not impressed.

"I was outraged, because she was without doubt the most outstanding woman in the Labour Party and she achieved so much," said the Labour MP.

Born in 1910, Barbara Castle was the youngest child in Labour family.

She grew up in Bradford and went on to Oxford University.

In 1945 she was youngest women to be elected in Labour's post-war landslide.

She put her victory in Blackburn down to "gin and nerves", and - as Emily Thornberry reflected in our interview - she made waves right from the start.

"She discovered fairly soon on that there wasn't a ladies' loo anywhere near the chamber, so she challenged the parliamentary authorities saying: The men have loos why can't we have one?

"They said: 'Oh, I'm afraid Mrs Castle it's not possible, the 19th Century plumbing doesn't allow it blah blah blah.

"Eventually it was all turned around and they said: Well of course you can have a ladies' loo behind the Speaker's Chair and it's there to this day, and when it was opened it was known as Barbara's Castle!"

When Labour leader Harold Wilson was elected prime minister in 1964, Barbara became only the 4th British woman to sit in cabinet.

She was the first ever overseas development minister, launching the department that is now known as the international development department. Two years later she became a somewhat controversial transport minister.

Harold Wilson was a close ally in the 1960s and 70s

"She didn't drive, she was a woman, she was put in charge of transport," says Ms Thornberry.

"They hated her. Can you imagine how much they took the Mickey out of her? She insisted that people should be breathalysed, and that they should wear seat belts, and all hell was let loose."

However, there were bigger fights to come.

Made secretary of state for Employment in 1968 - she would support Ford's female workers in their strike over equal pay, a battle depicted in the film Made in Dagenham.

In 1970, Barbara Castle would ensure that "equal pay" was indeed enshrined in UK law.

But - as industrial relations deteriorated - her 1969 paper In Place of Strife, which proposed forcing unions to vote before strikes, split the cabinet and alienated many of her friends on the left.

Emily Thornberry believes this was, in fact, a missed opportunity for her party,

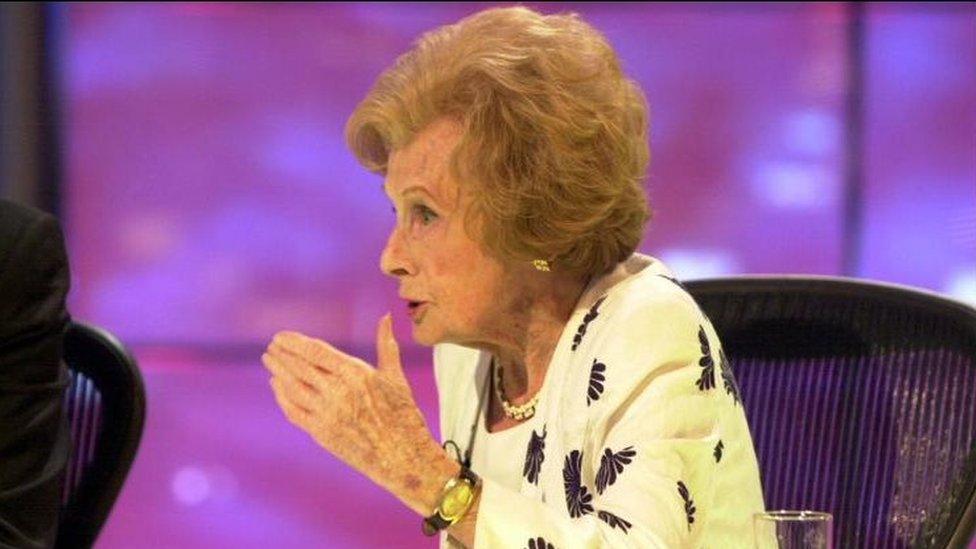

Emily Thornberry says she can identify with Castle

"To be quite honest if that had succeeded, if she had been successful, you do wonder whether we would have had the Winter of Discontent and whether or not we would have even have had a Tory government and whether Labour would have remained in power longer."

One colleague who never forgave her, was Jim Callaghan.

When Labour returned to power in 1974, Barbara Castle would take on the health and social services brief, introducing reforms including the link between pensions and earnings.

But when Callaghan became PM in 1976 there was a reckoning. He asked his health secretary to resign based on her age, a slight that Emily Thornberry retells with an obvious sense of indignation.

"He asked her to resign from the cabinet, because he wanted to lower the average age of the cabinet.

"She was two years older than him! She said 'I'm not going to resign - you'll have to sack me', and he sacked her!"

For Emily Thornberry, the social attitudes of the 1960s and 70s make Barbara Castle's career and achievements all the more impressive.

"I think she just used what she had, she was little, she had bright red hair, she was beautiful, so she used that to her advantage because the disadvantage was that she wouldn't be taken seriously because she was a woman."

Campaigning to get out of the Common Market in 1975

Refusing to conform would become a theme. When her husband Ted was made a life peer she became a "Lady", but Barbara refused the title until she received one in her own right in 1990.

It's a situation where few of us would find a parallel with our own lives, but Emily Thornberry - whose husband is High Court Judge Sir Christopher Nugee - is one such person.

"What she used to say, which I have to say is what I always say too - is that the honour that my husband has is his honour.

"If I ever got an honour for being me, as opposed to being an adjunct to my husband, then that would be different.

"My husband has achieved a great deal. I am hugely proud of him, but it is his achievement and not mine, I've never even ironed a shirt for him."

Barbara Castle in 2001: A fighter to the end

Having campaigned against Britain joining the Common Market in the 1975 Referendum, Barbara would later change her mind on the EU, spending more than a decade in the European Parliament from 1979.

Lady Castle's passion for politics never faltered. She would battle with her own Labour colleagues over restoring the link between pensions and earnings right up until her death in 2002.

Summing up her achievements for both her daughter and the rest of us Emily Thornberry said: "I would say that Barbara Castle was the most outstanding woman politician that the Labour Party ever had.

"She was not afraid of a fight, she achieved a great deal, whether that was in terms of international development, setting up that department, whether it was in terms of getting people to wear seat belts or getting women equal pay, or just being an example of what women can do, and should do.

"I think that is why people should remember her."

- Published26 January 2018

- Published2 February 2018

- Published23 February 2018

- Published23 March 2018