Ronan Point: a fifty-year building safety problem

- Published

The top of Ronan Point

At approximately 5:45am on Thursday 16th May 1968, Ivy Hodge lit a match. A duff connection between the gas main and her cooker, however, had allowed gas to leak into the kitchen. The cloud exploded, throwing her to the floor. She was knocked out and received some minor burns. And when she came to, found a large portion of the 22-storey high rise in which she lived had collapsed.

The Ronan Point disaster took place almost exactly 50 years ago, and there are clear parallels to Grenfell: in both cases, government policy was pointed at one objective but lost sight of building safety. In recent years, energy efficiency was the goal: hundreds of buildings were funded to install insulation on their exterior walls. In 1968, the target was mass-building of new homes.

Sir Keith Joseph, as housing minister from 1962 to 1964, had called for a rise in house-building productivity to cope with the postwar baby booms and wartime bombing. Ronan Point was part of the answer to that call: a brand-new tower block, built using modern techniques that required little skilled labour - or even scaffolding. It was one of the new "Large Panel System" designs.

Hannah Brack, an independent researcher, has uncovered records which show Anthony Greenwood, the housing minister at the time of the collapse, wrote to Prime Minister Harold Wilson on that very day worrying about central government culpability: they had "pushed" the design onto local authorities.

The explosion was not huge. Miss Hodge survived - so did her oven, which she took to her new home. When estimating the size of the force applied to the wall, the inquiry notes her eardrums did not burst. But, in the words of the official inquiry, the force was enough to blow out "the external load-bearing flank walls" of the flat.

In short, the blast knocked out the wall supporting the flats above hers. They, in turn, fell down with enough force to destroy the floors beneath hers. It is a miracle that only four people were killed. Had it occurred later in the day, when more people were in their living rooms, it could have been much higher.

Ronan Point is the tower at left, with the collapsed edge visible

Panel built design

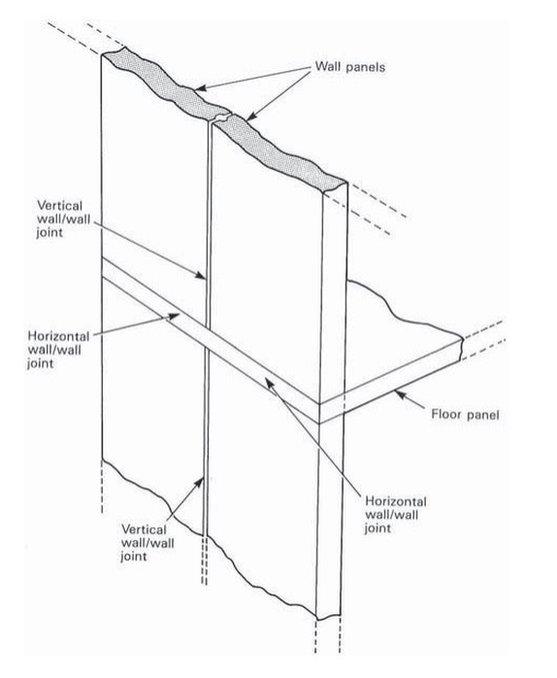

The panel-built system is a vulnerable design: in short, you took big panels of concrete. Then, with a crane, you stood up some panels to act as walls, then laid others horizontally on top of them to be floors and ceilings. When you had done one floor, you climbed on top of it, and then did the next.

Diagram showing how the floor panels were stacked and held by the wall panels

The design was simple, but had two terrible problems.

First, was the importance of the joints. Load-bearing walls could be knocked out, as at Ronan Point, if the walls and ceilings were not joined effectively. Technical guidance from 1968 on these buildings actually stated: "One can hardly over-emphasise the absolute necessity of effectively joining the various components of the structure together in order to obviate any possible tendency for it to behave like a 'house of cards'"

But bolts to hold them together were often missing. Cavities that should have been filled with concrete were found stuffed with rubbish and newspaper. The buildings were built by unskilled workers paid on a piecework basis: in short, they got paid more for working faster.

Second, there was a problem with fire. If you have a fire in a flat, the ceiling panel above the fire will heat up faster than the rest. That will mean it expands, and presses the walls outward. That can create large holes in the walls, through which fire, heat and smoke can spread.

In extremis, the fire could cause panels to fall out of the wall, and cause collapse.

In 1984, Newham ran a test on the then-unoccupied Ronan Point. They set a fire in a flat to see how serious these issues were - but stopped it, fearing the whole building would fall over.

The fire in Ronan Point, lit as part of an experiment into the effect of fire on the building

The aftermath

So what happened next? There were lots of buildings built to the same design. They were ordered to be checked and strengthened, and gas supplies were removed from them. The most important response was replacing gas cookers with electric ones.

Lots of these buildings survive: Ms Brack has found at least 1,585 of them still standing. There are 200 towers with 20 storeys or more. You can recognise them easily: they should still have no gas fittings, and usually have a sign that tells residents they are banned from bringing calor gas into the building.

Lots have also been pulled down. What we have left has been looked after: councils have invested a lot in strengthening works. But during the investigations following Grenfell, boroughs have found major problems with their towers: the Ledbury Estate in Southwark was evacuated.

Since then, concerns have been growing in official circles about just what state these towers are in. In August last year, the government asked local authorities to check their large panel system buildings. In Leicester, a tower is being demolished. In Portsmouth, two towers are being emptied to permit strengthening works. In Hammersmith and Fulham, two towers are being reinforced.

Victims of the Ronan Point disaster being taken away

The government has asked the Buildings Research Establishment - our key laboratory for building safety - to see if it can update its guidance on how to keep these buildings in a safe condition. To assist with that, a tower in London being demolished is going to be inspected as it is taken apart to see if we can learn more about how they were put up and how they have aged.

The ministry of housing told Newsnight: "We continue to monitor these issues through our comprehensive building safety programme and will provide further guidance if that is needed."

But, looking ahead, as they age, the chance of problems rises. Time is not making them better built or rendering the materials stronger. Wind, heat and rain take a toll. Metal bolts rust, expand and cause cracks in the concrete around them (so-called "concrete cancer"). So what now? Central government should think about what comes next.

There are strong reasons not to take down buildings precipitously. Local authorities and housing associations have strong financial incentives to keep these buildings in service as long as possible. And to the people inside them, they're homes - homes with big, airy rooms and, for lots of residents, nice views.

But these buildings are entering the end of their service lives. The vulnerabilities are growing. Central government may need to work out a plan for decommissioning the surviving LPS towers in an orderly manner. We got 50 years out of buildings that were poorly built to a fundamentally flawed design. We should not push our luck - or wait for it to run out.

- Published1 November 2017

- Published4 June 2018