The long march of Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party

- Published

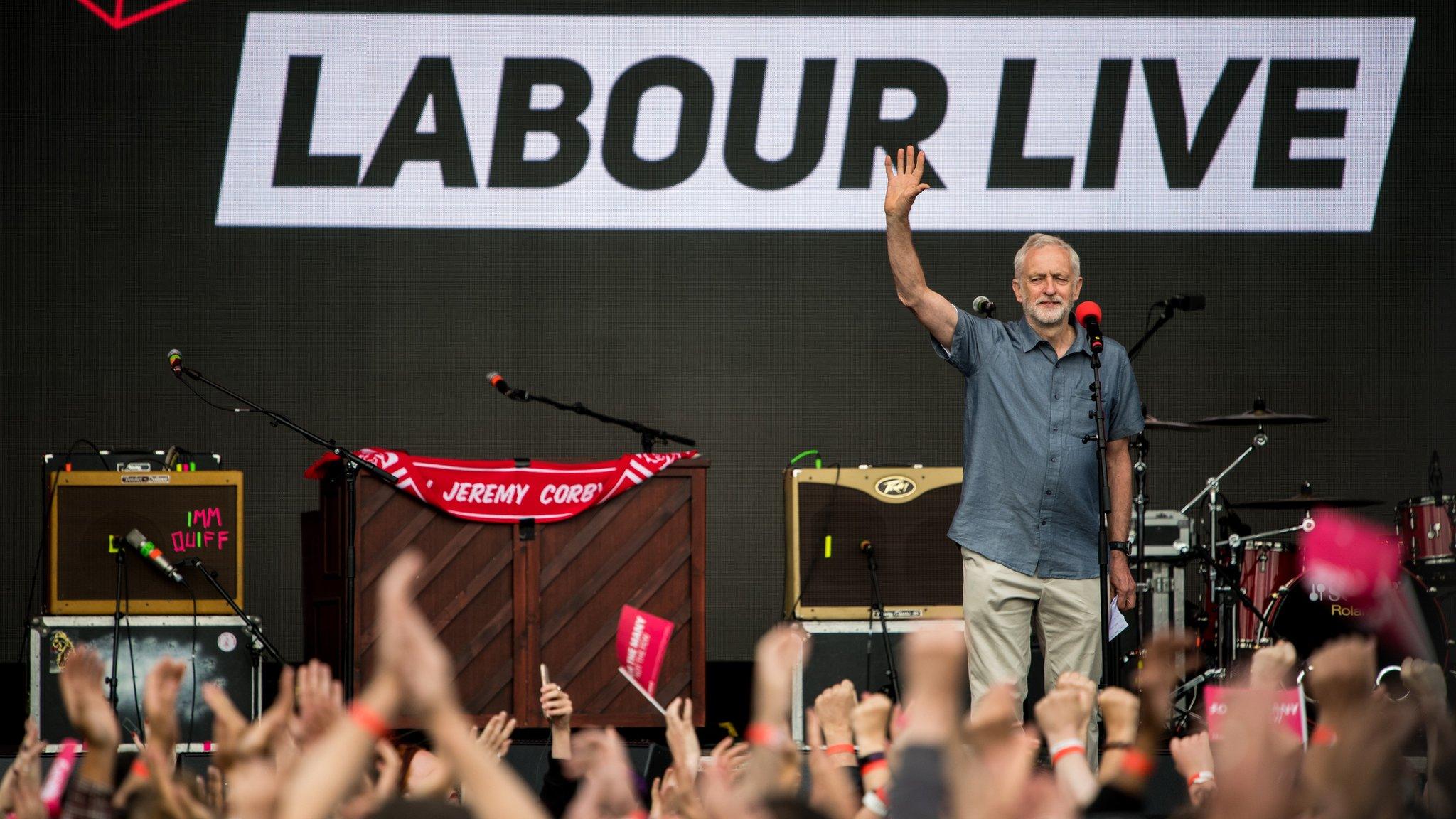

Jeremy Corbyn salutes the crowds at Labour Live, the party's music and politics festival

"Things can change - and they will." A hopeful, positive message. Or a warning?

These words were uttered by Labour's new leader Jeremy Corbyn at the special conference on 12 September 2015 when he decisively defeated the three other candidates.

I was in the room at the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre in central London - an odd place perhaps for a republican to be "crowned" party leader, perhaps.

But it proved convenient for Jeremy Corbyn as it was within yards of a pro-refugee demonstration in Parliament Square which he addressed soon afterwards.

His election was greeted by the strangest mixture of elation and trepidation. Three years on, and there is little doubt that he has changed his party.

Speaking this month at the Labour Live event on home turf in north London he declared: "The Labour Party is now 550,000 members - the biggest in my lifetime.

"We are a proud and determined party. We need and can do things differently."

In the final edition of BBC Radio 4's documentary series The Long March of Corbyn's Labour I've looked at how the party's membership has changed, the implications of this for policy - and how a mass membership party can bring challenges as well as opportunities.

March of the members

Under a cut-price supporters' scheme introduced by Corbyn's predecessor Ed Miliband, people who had felt either alienated by mainstream politics or who had been to the left of the Labour leadership signed up to back the insurgent in the 2015 leadership contest.

Once Corbyn was on the ballot, his campaign manager John McDonnell coined the phrase "straight-talking honest politics" - portraying him as a refreshing change from career politicians and the former ministers and special advisers who were his opponents.

Having been an MP since 1983 and a councillor before that, it could of course be argued that Corbyn, too, was a career politician.

But he looked and sounded different.

And some of those who signed up to support him stayed on - becoming full members and, as it turned out, a bulwark against a sceptical - even hostile - Parliamentary Labour Party.

Labour membership is falling back a bit now and confidential internal projections which we have seen - and which are used for financial planning purposes - predict it will decrease to around 500,000 by the end of the year.

But this is still two-and-a-half times bigger than when the party boasted of its "ground force" in the disastrous 2015 election campaign.

Soon after Corbyn's victory, a veteran of the party's left - Jon Lansman - was approached to set up, rather ambitiously, a whole new movement: Momentum.

Lansman had been a key figure - nearly 40 years previously - in Tony Benn's campaign for Labour's deputy leadership.

Momentum's aim in the short term was to ensure that Corbyn wasn't toppled.

"It was founded out of his leadership campaign," Lansman said.

"I was asked to do that job by John McDonnell, with the consent of Jeremy. As a result of that, we created something which looks actually very different from anything else on the Left - inside or outside of the Labour Party."

Corbyn initially put together a reasonably broad-based shadow cabinet but at local level, the party was changing.

Lucy Powell was chief of staff to Ed Miliband when he led Labour and, not long after he lost power, she witnessed a party in a state of metamorphosis.

Labour history

Looking through Labour's archives with Manchester Central MP Lucy Powell

I met her in her Manchester Central constituency - and chose as a rendezvous the People's History Museum on the banks of the River Irwell.

Deep in the basement of the museum is where the Labour Party stores its national archives.

Here you can see letters signed by Labour's first leader Keir Hardie (rather like contemporary leaders, he was drumming up financial support from the unions).

In more recent correspondence, Peter Mandelson and pollster Philip Gould discussed a review of party policy under Neil Kinnock - a prototype of the New Labour project.

Lucy Powell told me she brought Jeremy Corbyn here when she had, briefly, been in his shadow cabinet.

Although already reshaping the party for the future, he was fascinated by its past.

She told me: "Jeremy's staff were having kittens because he had to go to another function. He just didn't want to leave."

The archive also contains records of disciplinary cases and expulsions - underlining that the party has been riven many times by factional struggles before.

Sadly, the minutes of Parliamentary Labour Party meetings are closed for the next two decades so we can't read for ourselves of the fractious meetings between Corbyn and his sceptical MPs.

Festival-goers relax during Labour Live

Lucy Powell herself left one of those meetings two years ago in some distress.

She told me of the culture shock in her constituency when new members flooded in to support Jeremy Corbyn.

"My constituency membership went up from 600 to 700 three years ago to over 2,300, it's now gone down a bit again.

"It quadrupled in size, and that has brought great challenges as well as real opportunities... there was a bit of 'us and them' about it originally, with the older members calling newer members 'hard-left trots' and newer members calling the older members 'right-wing Blairites'."

Now though, she insists members are working more co-operatively together: "We've definitely come through that and a lot of those relationships have now been established, but it was definitely difficult for a while."

John Stolliday was until this month one of Labour's most senior officials - the director of governance and legal.

He announced his resignation when Jeremy Corbyn's supporters tightened their grip on the party machine and installed a new general secretary, in overall charge of the party's head office.

He joined Labour HQ 14 years ago, serving four party leaders - and had a broad overview of the changing nature of the party.

Giving his first-ever interview, he described the rise in membership in 2015 as "extraordinary.... no one saw it coming".

But who were these new members?

"There were many young people who have never been members of political parties and who felt genuinely enthused by Jeremy and his message."

But, he explained, they weren't all political virgins.

"There are many people who have joined from other political parties, from the Lib Dems, the Greens, the rag tag assortment of far-left parties and the Trade Union Socialist Coalition... and then also people who were members under Blair and then left because of the Iraq war."

And there is a bit of snag about where the new members are geographically, rather than politically.

"They are concentrated in London and the south east of England. That's a problem.

"For Labour to get into power, it absolutely has to win the constituencies with the smallest Tory majorities."

"They are in the Midlands and the M6 corridor in the North. They are home to many working class people.

"And for some reason these people are not turning out to vote for the Labour Party - or indeed to join it."

But the new members were certainly in the right place at the right time for Jeremy Corbyn in Labour's internal battles.

Putsch comes to shove

In his first six months as leader, party membership was rising but Jeremy Corbyn's political stock was falling.

Behind in the polls, he looked vulnerable.

But it was an attempt to oust him that solidified him in power.

After what was seen as at best a lacklustre campaign on his part to keep Britain in the EU in 2016, his internal opponents made a move - but also made a series of miscalculations.

The Parliamentary Labour Party decided they had no confidence in their leader. Eighty per cent of MPs opposed him, and many of the better-known faces left his shadow cabinet.

Two assumptions had been made by his critics, and both turned out be wrong.

The first was that having lost the confidence of so many of his MPs Corbyn would feel under a certain responsibility to resign.

Jeremy Corbyn comfortably saw off Owen Smith's leadership challenge in 2016

There seems little doubt he considered this, but those close to him say he didn't want to let down the members who had elected him.

The second was that - in line with legal advice party officials had obtained - if his leadership was challenged, he would need 20% of MPs and MEPs - around 50 elected politicians - to nominate him to get on the ballot paper. It was assumed this would be too high a threshold to meet.

In fact, in the end Labour's national executive - which wasn't under his full control at that moment - narrowly voted to put him on the ballot automatically without the need for nominations, and a subsequent legal challenge to this failed.

Compounding this, his opponents couldn't agree a candidate and there was an internal contest within the parliamentary party between Angela Eagle and Owen Smith.

Lucy Powell - one of those who resigned from Corbyn's shadow cabinet - regrets the move: "It was a really big mistake. It was a collective misjudgement of what action should have been taken at the time.

"It wasn't a plan. In fact if it had been a plan, it would have been a rubbish plan. It was a domino effect that took hold really, really quickly."

And John Stolliday also believes that emotion rather than wisdom prevailed.

Membership had been falling from its peak and he thinks some of the newer members may have gone - or lost interest - if a leadership contest had come later: "I understand why the challenge came. But the MPs who led that challenge seemed to not realise the strength of feeling amongst the membership.

"They forgot that many members of the Labour Party joined in 2015 to support Jeremy Corbyn.

"When people joined the Labour Party they join on a year's contract.

"For many people that would have expired in the summer, members were already dropping off by the time of the referendum in June.

"The effect of the challenge… was to invigorate and electrify members."

Left foot forward

This was the Left's moment.

The push against Corbyn was portrayed as a putsch - a coup against the membership.

And Jon Lansman, Momentum's founder, said the Left could no longer be quite so relaxed about who controlled the levers of power in the party.

"We expected it to come. And whilst Jeremy set out to be inclusive, we prepared for it."

Momentum was initially riven with factional strife - and a debilitating debate over whether its activists also had to be fully paid-up Labour members.

As Lansman put it: "Any start-up organisation goes through a painful period of creating itself."

But with a threat to Corbyn, enmities could be buried or shelved - and those on the Left could come together in common cause.

That summer, Jeremy Corbyn played to his strengths - and played to the crowds - at leadership rallies. Momentum managed an impressive social media campaign.

Pop acts and Corbynistas rubbed shoulders at Labour Live

And he was re-elected with a higher share of the vote. A victory for Jeremy Corbyn but also for Momentum.

Jon Lansman was delighted: "We raised a great deal of money. We only had two or three thousand members before the coup. We came out of it with 20,000. We now have more than double that."

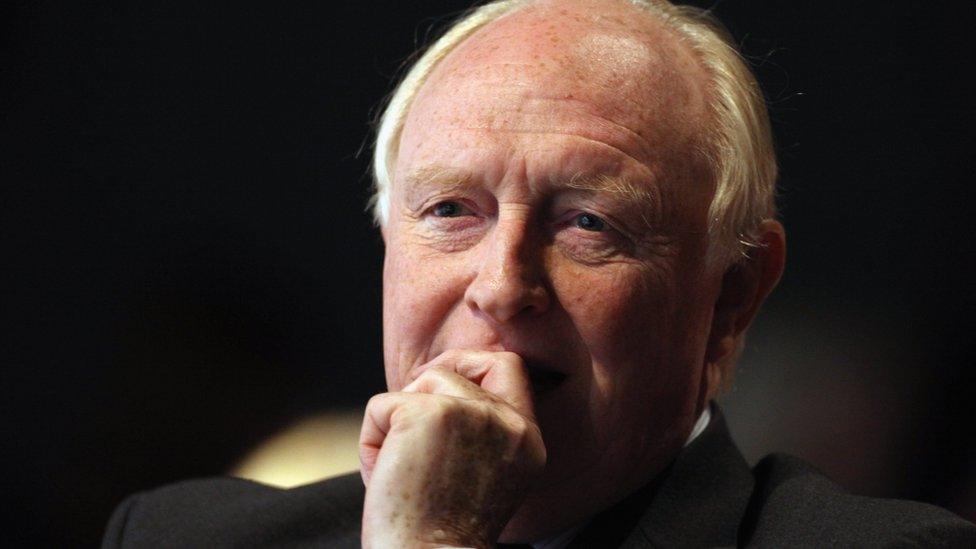

But a former Labour leader, Lord Kinnock - who had started out on the Left - felt too much time had been spent by Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters on changing his party rather than looking outwards to change the country.

"I would say that Jeremy, and I doubt that he would disagree with this, comes from a segment in British politics, in Labour politics that has always existed, and is largely composed of people who give a higher priority to power in the Labour Party than power for the Labour Party.

"And if they're ideologues it means that they have a convenient life because it means they only have to make a decision once in their life.

"You can't drive a car or bring up a family like that. I don't think it is the reality of life."

But even after Corbyn's second leadership election, elements of the party machine - including crucially the national executive - weren't fully in his hands.

That came later - after the 2017 general election.

Although some seats were won by Labour MPs who publicly distanced themselves from Corbyn's leadership, the massive increase in the share of the vote led to the abandonment of two putative leadership challenges and from this point on, many of his internal opponents kept their heads down and their tongues bitten.

John Stolliday says there was an active debate about broadening the political base of the shadow cabinet, but it didn't happen: "There was an opportunity straight after the 2017 election for Jeremy Corbyn to look at the issues facing this country and to say 'I need the full range of talents of this party and that includes the senior and serious figures, the former ministers, who are on the backbenches now'.

"Jeremy had an opportunity to put these people in to his shadow cabinet and to say 'this is a united, unified party'.

"Unfortunately he chose to reject that - and decided to instead reward loyalists and loyalty."

Indeed Jeremy Corby's supporters tightened rather than relaxed their grip following the election.

Behind-the-scenes changes were resisted in a token fashion at best.

As a senior figure in the parliamentary party confided off the record: "The lunatics have taken over the asylum, it's just a game of survival for most of us - we are ploughing our own furrows and waiting for the madness to pass."

Levers of power

To reflect the much-expanded membership, three new seats were added to Labour's national executive, or NEC - and all three of these new positions were taken by members of Momentum, including its founder Jon Landsman.

John Stolliday explained the importance of Labour's NEC: "In the Labour Party, control of the NEC means that you control every decision that happens internally.

"So, whether it's picking the longlist or shortlist for a by-election to see which candidate is going to be selected, whether it's deciding the party's priorities, the rule changes that will happen at conference, every decision is made by the NEC - control of the NEC is absolutely vital."

Another less well-known body has also had a change of management.

The former GMTV political editor and MP Gloria De Piero and the former Eastender and Labour peer Michael Cashman - seen as supporters of New Labour - were outvoted as members of the Conference Arrangements Committee by the left-wing former trade union leader Billy Hayes and a community worker and constituency activist from Tottenham in north London, Seema Chandwani.

The committee influences what is discussed and when at Labour's annual gathering.

Seema Chandwani is a member of Momentum and a left-wing group with a longer pedigree - the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy.

She saw this as a victory for democracy after many years in which, she believes, the Left had been kept well away from the reins of power, as well as a consequence of the expanded - and younger - membership.

"These weren't random Martians coming from Planet Momentum. These were people who are active in our communities.

"It struck a modicum of fear in some of the current members who were saying 'oh, we are going back to the eighties'.

"But I said, what happened in the eighties? I was four in the eighties."

So important parts of Labour's machinery are now operated from the Left. But not everything has changed.

Swathes of the Parliamentary Labour Party - while cowed - remain sceptical of Corbyn's leadership.

One senior figure told me "the Corbyn phase will be over - when we lose the next election". He believes we have seen "peak Corbyn".

But as the 2017 result proved, the political future can be difficult to predict.

And there are further changes to the Labour Party being planned in the name of empowering the mass membership.

A "democracy review" is in full flight.

Both Momentum and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy are suggesting that the way the party's parliamentary candidates are selected should change, making it easier for party members at local level to trigger contests rather than re-adopting a sitting MP on the nod.

This isn't, however, what's often referred to as mandatory reselections - effectively requiring MPs to get the backing of members in every parliament.

The Left hasn't exactly been overwhelmingly successful at getting its candidates selected under the current system.

The new MP for Lewisham East - elected this month - was not backed by Momentum or the influential left-wing Unite trade union.

Local councillor Janet Daby was supported by groups that would once have been described as Brownite and Blairite - the campaign groups Labour First and Progress - though it's a measure of how the party has moved to the left that Janet Daby is now regarded as a "moderate".

She voted for Jeremy Corbyn in both leadership contests.

Lucy Powell said: "I don't think you can see Momentum as a homogenous force sweeping the party. They are more effective when they are mobilising people online.

"When it comes to local selections they have been much less effective because usually what people go for tend to go for a good strong committed local person.

"Trying to parachute in a Momentum or Unite-favoured candidate doesn't work."

New Lewisham East MP Janet Daby was not the preferred choice of Momentum or Unite

For Jon Lansman, though, time and effort will deliver. Perspiration is as important as inspiration for him: "The party is a fundamentally different party and is committed to radical change.

"The effect of having so many new members will eventually flow through. It hasn't got there yet.

"Local government is hardly touched by the new membership, with the exception of one or two authorities.

"We're still in the early days of trickling through the system.

"For local government and then for Parliament - because you select a proportion of candidates every time - that will flow through.

"I don't think there is any going back."

Momentum is running training sessions for new councillors, who in turn may become MPs.

'That's democracy'

But even if the make-up of the Parliamentary Labour Party doesn't change dramatically in the short term, its power is set to diminish further.

In 2015, candidates for the party leadership needed to demonstrate support from 15% of MPs and MEPs.

This was reduced to 10% at last year's Labour conference.

And now the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy wants the ability to shut out politicians from this process entirely.

They are suggesting - when the time comes and Corbyn goes - that any candidate who wants to replace him would simply need to have the support of 10% of constituencies, or 10% of affiliated trade unions to avoid the need to have the backing of one in 10 of the parliamentary party.

Seema Chandwani explained the thinking: "You have got these shortlisting gatekeepers called MPs who have been elected to have that role.

"From the perspective of the lay-member, should there really be any type of gate-keeping to get on the ballot paper?

"The leader of the Labour Party is there not as the property of the MPs, they are the property of the whole party."

I asked her if these rule changes were more likely to result in a successor to Jeremy Corbyn who was just as left wing. She responded: "It would be more likely that his successor is somebody members want. And if somebody they want is more Left, then that's democracy."

Radicalism versus reality

Jeremy Corbyn called his 2017 general election manifesto the star of the campaign and it's clear that Labour would tax more and spend more - those earning more than £80,000 and big corporations would pay more tax, and some services in private hands - such as the water industry in England and Wales - would be returned to the public sector.

Many of the newer members in particular are delighted to see clear red water separating the opposition from the government.

But there are fears that the enthusiasm of a mass membership could turn to disappointment - disillusion even - if the party doesn't deliver quickly enough on the pledges that Jeremy Corbyn recites at party rallies.

One council that is already in the Momentum mould is Salford in Greater Manchester.

Its mayor Paul Dennett is a strong supporter of Jeremy Corbyn.

He shares his leader's passion for housing - and council housing in particular.

The local authority has set up a housing company that embodies radicalism in its name. It's called Derive. But it's pronounced Dereeve.

Salford in Greater Manchester, where the council has set up its own housing company

The name was derived (not dereeved) from Guy Debord, a member of the Paris-based Marxist Situationist collective, the Lettrist International - which, naturally enough, split from the Letterists - in the Fifties.

It's all about designing urban environments around emotion and human behaviour.

But looking at the company's construction plans in the mayor's office, the housing probably owes a bit more to Brookside than Bauhaus.

The development that's getting under way is a mix of housing for rent, shared ownership and home for sale.

This is hardly a return to the days when the ultra-left Militant Tendency (or Revolutionary Socialist League) controlled Liverpool Council, culminating - as then Labour leader Neil Kinnock put it in 1985 - "in the grotesque chaos of a Labour council - a Labour council - hiring taxis to scuttle round a city handing out redundancy notices to its own workers".

Dennett, a Momentum member, has coined a term for his rather different approach: "It's what I would refer to as sensible socialism. It's a pragmatic response to the context in which we find ourselves.

"That isn't to say we're not trying to change the system."

With eight- yes, eight - new rented homes in the pipeline he knows he is making only a modest start but believes when a Labour government ends austerity, it will be possible to play his part fully in delivering the party's million homes pledge.

For now he is giving a glimpse of the possible - erecting a signpost to a future direction.

But he also has to work hard to manage the expectations of party members.

"This is a continual challenge," he says.

"I regularly attend branch meetings and we have got party members who see the manifesto and want me to implement it as quickly as I possibly can.

"It's been interesting to go through some of the policy and resource complexity with party members and in terms of their expectations around delivery they become more realistic."

If this is a challenge locally, the shadow communities secretary Andrew Gwynne - also Labour's joint election co-ordinator - knows it could be a nightmare nationally.

"What gives me sleepless nights is that so many of the big ticket promises in Labour's manifesto will be down to local government to deliver," he tells me.

"The worry for me is the ability and capacity of local councils to be able to deliver."

Hope or disappointment

Behind the scenes in Whitehall, Labour has been preparing for government - with each shadow departmental team being given advice by the former head of the civil service, Lord Kerslake.

Andrew Gwynne believes the party needs a clearer plan, and to be honest about which parts of Labour's manifesto can't be delivered swiftly if hope isn't to be eclipsed by disappointment.

"It's going to take time to overcome eight years or more of Tory austerity. It is going to take time to build up capacity in central government, it is going to take time to build up capacity in local government and we've got to ensure that we have that right mix of offering hope and optimism and people being able to see change, but also not disappointing that change hasn't been quick enough or radical enough."

He also warns of the dangers if Labour fails to reconcile aspirations with the art of the possible.

"If we come to power on the back of massive optimism, a new way of doing things, and we fall at the first hurdle then it will be very difficult to recover."

Former Labour leader Lord Kinnock says the party has to "compromise" with the electorate

Lord Kinnock - as Neil Kinnock - began as a protégé of left-wing Labour leader Michael Foot in the 1980s.

But as he moved to the centre, the party picked up support.

He is urging the current leadership to "compromise" further with the electorate if its 40% at the last election is to be a building block not a ceiling.

He thinks this may mean that party membership falls a bit, with some people drifting off to protest groups, but the prize would be wider support.

"There has to be compromise with the electorate. And if the electorate isn't supporting you - you can't invent another one.

"You have to deal with the people that exist, that have needs and hopes, and serve those needs and hopes in a way they can comprehend and can embrace."

United we stand?

There have also been unanticipated consequences of a mass membership.

Sometimes in politics arguments emerge over means rather than ends.

The leadership of both the country's biggest union, Unite, and Momentum wanted to see Labour move to the Left, and to keep Jeremy Corbyn at the helm.

But there are differences over personnel - and how to preserve the leader's legacy.

For many in Momentum - some of whom haven't risen through the ranks of 'organised labour' - a more democratic party that shifts power to the members is the best way of ensuring Labour remains on the Left.

If this or that left-wing union general secretary were to be ousted, they fear the party - or at least its machine - in turn could drift to the the right.

For example, the left-wing Unite leader Len McCluskey faced a leadership challenge last year, and then a legal challenge to his victory.

Had he been removed the left-wing delegates he in effect appoints to Labour's ruling national executive could also have been replaced.

A sign of this tension was when, briefly this spring, Momentum's Jon Lansman declared he would apply for the post of the party's most senior official - the general secretary.

In doing so he was defying the party leadership who wanted to install the Unite official Jennie Formby.

He later withdrew, telling me he simply wanted to see a "proper process".

But these tensions have surfaced again recently - in Wales.

Labour' s leader in the principality, the first minister Carwyn Jones, has announced he will stand down in the autumn.

There is now a battle not so much over who should succeed him, but how his successor should be chosen - though the latter could determine the former.

The method of selection is an "electoral college" giving unions and elected politicians two thirds of the vote and consigning grassroots members to one third.

There will now be a hastily-arranged special conference in September to decide whether these rules should be changed - and those on the left in particular are calling for the power of selection to be in the hands of the rank and file.

Darren Williams - a left-wing member both of Labour's ruling national executive and its Welsh executive - insists that changing the leadership rules is about more than faction-fighting.

"Some of the resistance to a one member one vote contest in Wales comes from people who assume that [it] is more likely to favour a left-wing, pro-Corbyn candidate but I think there are arguments just based on which is the more democratic system."

Unite leader Len McCluskey - handing out ice creams at Labour Live - saw off a leadership challenge last year

But four big unions are resisting this move.

Mike Payne, of the GMB union in Wales, is warning that weakening the union voice in a leadership contest could have unintended consequences: "The trade unions have always been the consistent body within the party that keeps it stable.

"If you take away the voice of organised labour then the party becomes a mile away from working people on a day to day basis and becomes remote.'

The UK leader is already chosen by the members but John Stolliday expects similar underlying tensions to become more apparent: "There is a fundamental conflict Labour has to face in the next year or so.

"Whether it is a party of the membership or of the trade unions and those who created it. It's almost an existential problem.

"There is a delicate balance... it becomes more of a tyranny of the majority if one side gets to rule the roost."

Seema Chandwani has a foot in both camps - an activist in her constituency and with her union, Unite,

She says: "Who is in charge of the party - members or the affiliated organisations? That's been there pre-Corbyn and there is always going to be that tension of how do people maintain and use power.

"I am not going to tell you there isn't going to be that tension or it's all going to be lovely."

Out of step on the long march

And the leadership is challenged when the mass membership aren't quite in step with them.

The Labour Live event this month wasn't a sell-out, politically or in terms of tickets.

There were a few exceptions, but it was overwhelmingly attended by staunch supporters - admirers, even - of Jeremy Corbyn.

But many also sported fluorescent stickers opposing, with rather colourful language, Brexit.

Some Labour Live attendees voiced their displeasure at Labour's approach to Brexit

A survey of party members carried out by Queen Mary University and YouGov suggested more than eight in 10 members supported staying in the single market - something Jeremy Corbyn hasn't, and possibly won't, endorse.

Some of those wearing the stickers said they were simply expressing "disappointment" at Brexit, and not at the position of the party leadership.

But Brexit is an issue which cuts across left/right lines - with even some grassroots members of Momentum calling for a new referendum.

Jon Lansman explains the difficulty: "It's very difficult to navigate - to win elections we need to take people with us with a range of views on Brexit.

"So far Jeremy has done that extremely well. It may get more difficult."

Whatever the tensions over specific issues - proof, John McDonnell would contend, that the party leadership doesn't suppress what he calls "robust debate" - those on the left would argue that the political ground is shifting and that the membership are united by their radicalism.

Time and again, leading Labour figures including Jeremy Corbyn use the word "transformation". They don't just want to change this or that tax rate, they really do want to change society.

Many would buy into a concept popularised - if that's the word - by the Italian politician and Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, who developed his thinking in the 1930s when he was imprisoned by Mussolini's regime.

He argued that the ruling class exercised "cultural hegemony" - in effect that they imbued society with their assumptions, which became the received wisdom.

So it wasn't surprising Labour Live was billed as a cultural as well as a political festival.

Labour's leadership believe they have overturned what they term "the neo-liberal consensus" and have challenged the efficacy and morality of austerity.

Jon Lansman believes that if a left-wing government does take power - despite all the constraints set out by Andrew Gwynne - vested interests will resist.

And it's at this point Momentum will prove its true worth, he says.

"We want to make a significant transformation. We want decisions which affect jobs and livelihoods democratised. The global corporations will resist. Other governments have faced challenges like runs on the pound. And we may face similar things. I hope we don't.

"The people who are opposed to doing what we want to do have one thing in their favour - money. We have people.

"We need the power of people to overcome the power of money."

The changing man

Of course, it's possible Jeremy Corbyn won't make it to Downing Street - that the clash of people and corporations just doesn't happen.

But the party he presides over has already changed.

And those around him are unsurprisingly confident that some of the changes that have been wrought in the past few years are likely to be permanent.

It was a relaxed shadow chancellor I encountered at Labour Live.

John McDonnell was in open-necked shirt, stopping to chat with journalists and supporters.

He told me that even if he and Jeremy Corbyn were to depart the scene Labour would remain an anti-austerity party - and "there will be no triangulation", where the main parties compete on similar territory.

"That has gone now," he tells me.

His close political ally Jon Lansman is confident, too, there is no going back to the politics of the Blair/Brown era.

"The party has fundamentally changed," he says.

"We're not going to go back to neo-liberalism, we're not going back to privatising the health service. That's decided forever. Well, for a generation or two."

But a measure of how the party has changed is that many of those who didn't back Jeremy Corbyn for leader are recognising this too.

John Stolliday - who joined Labour's head office under Tony Blair - believes the current leader has a stronger grip on the levers of power than New Labour's founder and frontman.

Momentum supporter Owen Jones and Progress director Richard Angell on Labour candidate selection

He said: "Blair controlled the party through the popular weight of his determination to get into power, and people were willing because he won power so overwhelmingly in 1997.

"Jeremy has uniquely managed to get hold of not just the membership of the party, but also of the NEC and the party structures.

"No leader has ever controlled all the levers of power at the Labour Party before."

And Lucy Powell - Ed Miliband's former chief of staff who subsequently worked on Andy Burnham's failed leadership bid - agreed.

"Jeremy can be the leader for as long as he wants to be. No-one is going to challenge that at all. We just need to get on with the job we're all elected to do."

But, she adds, "with power comes responsibility".

Others at grassroots level, groups that were more comfortable with the pre-Corbyn era - Progress and Labour First - continue to try to combat control by the Left.

Their members are not Marxists. They don't believe anything is historically inevitable. The Long March of Corbyn's Labour hasn't yet reached its destination.

The Long March of Corbyn's Labour is on BBC Radio 4 at 20:00 BST on 25 June and 11:00 BST on 27 June. It is presented by Iain Watson and produced by Katy Dillon and Adam Bowen