Political ads on social media must be transparent - Electoral Commission

- Published

- comments

"Urgent" action is needed to make online political advertising more honest and transparent, the UK's election watchdog has said., external

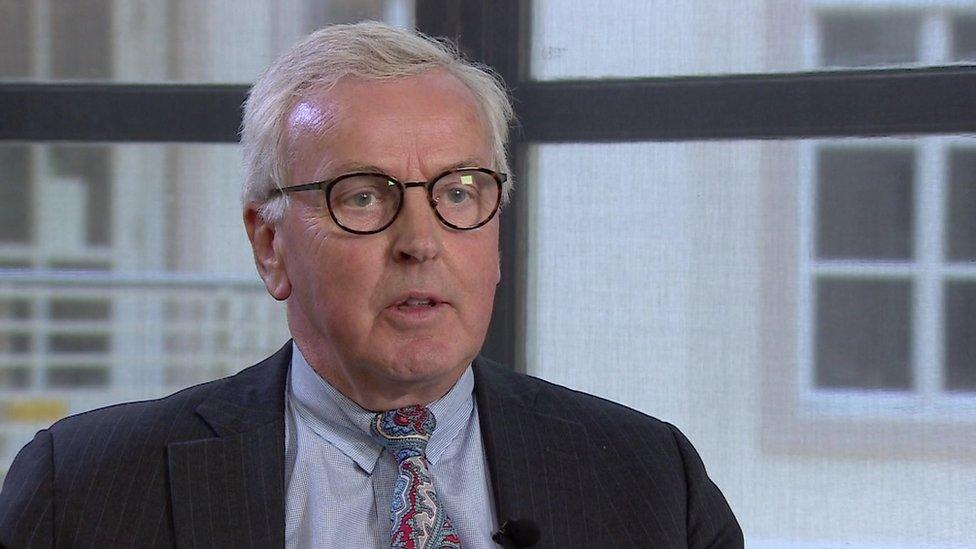

The head of the Electoral Commission, Sir John Holmes, said voters "need to know who is targeting them and how".

He wants digital ads to carry the name of the party or campaign behind them so voters know the source of any claims.

The government said it would launch a consultation on making the proposals law "in due course".

Election leaflets have to carry the name and address of the candidate's agent and who is paying for it - and the Electoral Commission wants online ads and messages on social media to be the same.

Sir John told BBC News voters "can have faith in the democratic process as it stands" but, he added, "what we are seeing is digital campaigning and use of social media exploding in all directions - that is why we think the rules need modernising and clarifying".

There is no law against making factually incorrect or untrue statements during election campaigns or referendums, unless they refer to an individual candidate.

Neither the Electoral Commission nor the Advertising Standards Authority see it as their role to monitor or police campaign lies and disinformation.

The Electoral Commission believes transparency is the best way to keep politicians and campaigners honest.

It argues that voters will be better able to judge how "credible" an online ad or social media message is if they know the source of it.

Sir John Holmes says the rules need modernising and clarifying

Research by the commission found voters were likely to engage with humorous campaign material, regardless of the trustworthiness of the source, without necessarily identifying it as part of the election battle.

The watchdog said there was nothing wrong with campaigners using "bots" - automated programmes that spread messages - or telling their staff to post campaign messages on social media.

"But these forms of campaigning are a problem when they are used to deceive voters about a campaigner's identity or their true level of support, or used to abuse people," it said in a report.

A scheme set up for the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, which forced campaigners to put links in social media images linking back to details about who created them, worked well, the commission said, although there was no way of stopping campaigners posting anonymous propaganda on message boards.

The Electoral Commission said the UK government and devolved administrations should be ready to impose direct regulation on social media companies if they fail to ensure ads carried on their platforms are legal.

It is calling on social media companies, including Twitter, Google and Facebook, to deliver their proposals for online databases of political adverts in time for UK elections in 2019 and 2020.

And it said the companies should put in place new controls to check that people or organisations who want to pay to place political adverts about elections and referendums in the UK are legally permitted to do so.

"If voluntary action by social media companies is insufficient, the UK's governments should consider direct regulation," said Sir John.

The Commission also recommended new checks to ensure that foreign money is not being used to influence UK elections and referendums.

The watchdog also wants to be given stronger investigatory powers as well as the ability to impose fines "significantly" higher than the current maximum of £20,000 for breaches of the rules.

A Cabinet Office spokesperson said: 'The government is committed to increasing transparency in digital campaigning, in order to maintain a fair and proportionate democratic process, and we will be consulting on proposals for new imprint requirements on electronic campaigning in due course."

- Published30 March 2018

- Published19 February 2018

- Published16 May 2017