How a Conservative PM faced a Rees-Mogg... in 1993

- Published

Newly released files show how, behind the scenes, John Major decided how to overcome Conservative MPs who voted against the Maastricht treaty in July 1993.

Summertime, Conservative civil war over Europe, and Rees-Mogg challenging the prime minister's European plans - but this wasn't Theresa May and Jacob Rees-Mogg but her predecessor, John Major, and his father, William, Lord Rees-Mogg.

And the battle was not over Brexit but the Maastricht treaty. This was the agreement that turned the European Community into the European Union (EU) and laid the foundations for the European single currency, the euro.

John Major had hailed the treaty, agreed in December 1991 by the then 12 member states, as a good deal for Britain. He praised the opportunities he believed a single market in goods and services, and the free movement of labour, offered. And he believed that a concession, allowing the UK to decide whether, not when, to join a single European currency, was key.

Eurosceptic MPs said the treaty would give the EU greater powers at the expense of Westminster. They saw it as a step down the road to a centralised federal EU. And they were implacably opposed the UK joining a single European currency.

In the Lords, the former Conservative Prime Minister Baroness Thatcher said that the treaty would "diminish democracy and increase bureaucracy".

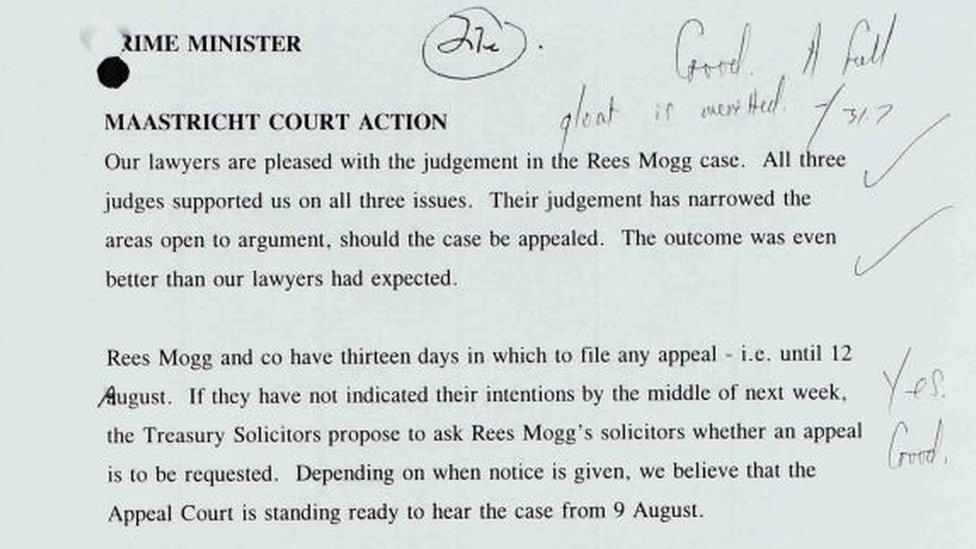

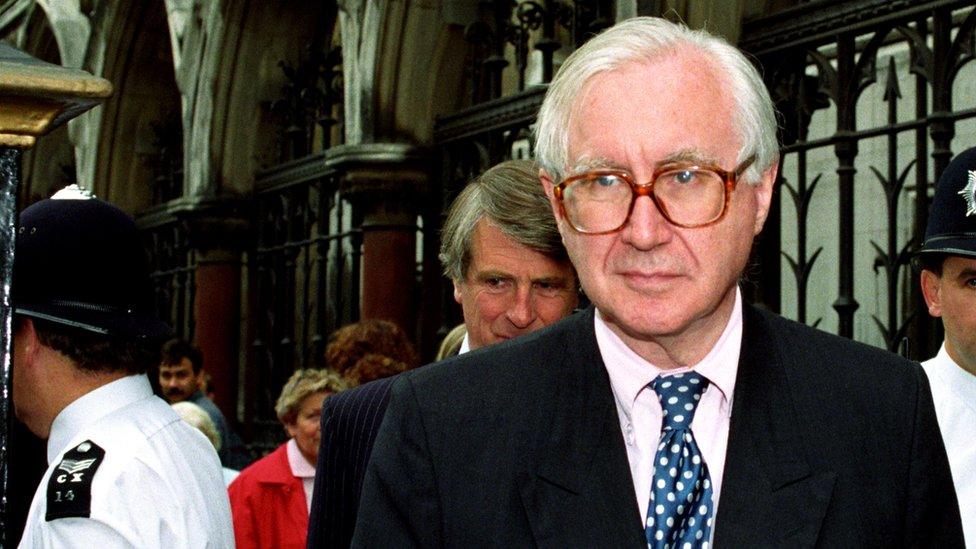

Lord Rees-Mogg went to court to stop the Maastricht treaty from becoming UK law - but judges supported the government's position, on all the issues.

"The outcome was even better than our lawyers had expected," Sir Roderic Lyne wrote on a note.

He pointed out that Douglas Hurd, then Foreign Secretary, was "exercising restraint" in public as he did not want to "provoke the Rees-Mogg brigade" into "further Quixotic action".

John Major enjoyed the moment. "Good," he wrote on the document, "a full gloat is merited."

Lord Rees-Mogg made an unsuccessful legal bid to block the Maastricht treaty

Getting the treaty through the Commons took a year. Those who opposed it, from the Labour as well as Conservative benches, were vocal and well organised. But by July 1993 the end of the process was in sight.

"It was the toughest time I spent in Downing Street," says Sir Roderic, who was John Major's private secretary at the time. "I remember it as a nightmare."

John Major's strategy as the final vote loomed was a risky one.

He would, if needed, call for a motion of confidence.

If he had lost, the government would have fallen.

It was, in effect, the "nuclear option" - either back me or face a general election.

On 22 July 1993, after a series of close votes, the government lost the main motion.

The ratification of the Maastricht treaty had been blocked.

Then, in a moment of the highest political drama, John Major stood up at the dispatch box and announced there would be a vote of confidence in the government the following day, which would also act as a vote to write the treaty into UK law.

Conservative Maastricht rebel MPs included Sir Teddy Taylor (left) and Teresa Gorman

Seeing all the papers reminds Sir Roderic of how much complex information the prime minister had to digest.

"John Major has an incredibly quick brain" he says. "He has a mind like a high-speed computer."

He recalls how on 21 July John Major had been depressed, knowing he had lost the first vote.

He tried to work on a speech for the next day but lacked energy and went to bed.

"Everyone expected disaster," Sir Roderic says.

Yet when he returned to Number 10 first thing next morning, the prime minister was "perky".

"He had the glint of battle in his eye."

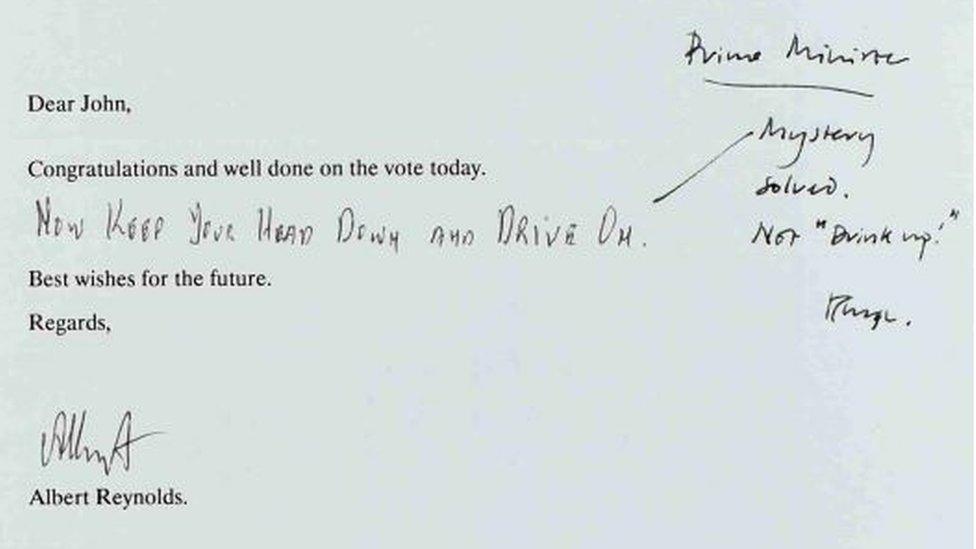

The Irish Prime Minister, Albert Reynolds, told Mr Major to "keep your head down and drive on".

John Major had worked out his plan to call for confidence motion and had held three cabinet meetings to get his ministers to agree.

His approach worked - opponents in his own party wouldn't vote against the government in a confidence vote.

"He basically lined the rebels up against a wall and aimed machine guns at them," as Sir Roderic puts it.

The vote was won, by 339 to 299.

John Major and his staff celebrated in his parliamentary office with champagne and congratulations arrived from European politicians.

Albert Reynolds, the Irish Prime Minister, was friendly with Mr Major and sent a message saying: "Well done.

"Now keep your head down and drive on."

Sir Roderic Lyne is reluctant to draw too many parallels between then and now.

"Theresa May is unbelievably resilient I think," he says.

"Her problem is far worse than Major. He was attacked by 25 MPs. She's under fire from both right and left. And while for us, the real pressure came in the last stages, she's had it for two years."