Are we living in a 'nanny state'?

- Published

- comments

Whether it is forcing restaurants in England to print calorie counts on menus or banning energy drinks for under-18s, the government is full of ideas about how to protect people from themselves.

Conservative politicians used to hate this kind of stuff. They called it the "nanny state" - conjuring images of a finger-wagging, bossy government forever telling us all what to do.

Margaret Thatcher - to her critics the epitome of a bossy, finger-wagging prime minister - often took aim at the "nanny state".

But one of the earliest uses of the phrase in Parliament came in 1980 during a debate on plans to make the wearing of car seatbelts, for drivers and front seat passengers, compulsory.

Former World War One fighter ace, and Conservative peer, Lord Balfour of Inchrye argued with great passion that seatbelts "can kill".

But his main objection to the plan was that it was "yet another state narrowing of individual freedom and individual responsibility".

Lord Balfour is strapped into a glider - with a seatbelt - on a visit to the Air Training Corps in 1942

Where would it all end, he wondered in a speech in the House of Lords, external.

"There are I believe 60,000 deaths a year from lung cancer. I cannot remember the starting of any pressure group formed of the medical community for compulsion on this matter.

"Regarding alcohol, there is possible legislation to limit the amount and conditions in which alcohol is taken which may reduce the terrible tragedy of bodies broken and constitutions wrecked by alcohol. I do not believe that the medical people have lobbied for compulsion there.

"Therefore, if we are to have what I term the 'nanny state'... why do not the medical lobby go for compulsory wearing of life jackets for people who swim, sail and row in boats?"

How times have changed.

Restrictions on the sale and advertising of cigarettes, like the compulsory wearing of seatbelts, have long since become law, spurred on by the medical lobby that was invisible to Lord Balfour, with curbs on alcohol consumption, through minimum unit pricing, coming down the track.

In some cases, these laws were passed by Conservative governments.

Swimmers have yet to be made to wear life jackets - but the idea that the state can, and should, use its power to force people to make better choices about their health and safety is accepted as a good thing across the political spectrum.

Supporters can point to the many lives that have been saved and how the public has, by and large, accepted curbs on what now seem like reckless, or downright dangerous, behaviours.

'Wood burning Gove': Truss fumes at cabinet colleague

Indeed, health campaigners and opposition parties argue that Theresa May's government - for all its commitment to cutting smoking rates and tackling childhood obesity - remains far too fond of industry self-regulation and not willing to take the tough legislative action needed to make a real difference.

But are there signs that the tide is turning on the Conservative benches? Is the ghost of Lord Balfour, who died in 1988, aged 90, haunting the corridors of power?

In the run-up to the Conservative Party conference, former minister and leading Brexiteer Priti Patel criticised the prime minister, external for leading a "nanny state government", which she claimed was more interested in banning things than implementing Conservative policies.

Chief Secretary to the Treasury Liz Truss - who has criticised the restaurant menu plan and called for motorway speed limits to be increased to 80mph - grabbed headlines in June when she took a swipe at cabinet colleague Michael Gove's proposed ban on wood burning stoves.

It is not the government's job "to tell us what our tastes should be", she said in a speech.

"Too often we're hearing about not drinking too much, eating too many doughnuts or enjoying the warm glow of our wood-burning Goves - I mean stoves.

"I can see their point: there's enough hot air and smoke at the environment department already."

Christopher Snowdon, of the Institute for Economic Affairs, a free market think tank which is reported to have received funding from the tobacco industry, said other Conservative MPs were similarly uneasy about what they see as the bossy tone of government initiatives, although few have been willing to go on the record about it.

Mr Snowdon is a longstanding campaigner against the "nanny state". He even compiles an annual league table of the most "nannying" countries, external - which last year saw the UK coming second behind Finland as the "worst country in which to eat, drink, smoke and vape in the EU".

Smoking in pubs was banned in 2007 by a Labour government

His ultra-libertarian views - he says he would have no problem with legalising all drugs, for example - puts him at odds with Theresa May and the rest of the Tory leadership, as well as mainstream opinion in Labour and just about every other party at Westminster.

He argues that they have all misread the mood of the public, who, he claims, are growing increasingly "fed up" with being told how to live their lives.

"I think there is a public backlash but it may not always be reflected in the media," he says.

It is mostly the poor and marginalised - people who don't always have a voice at Westminster - who bear the brunt of increased taxes on food, alcohol and tobacco, he argues.

Banning things is "very easy and cheap to do", he says, and it makes an immediate impact on people's lives - an irresistible combination for politicians looking to make a name for themselves.

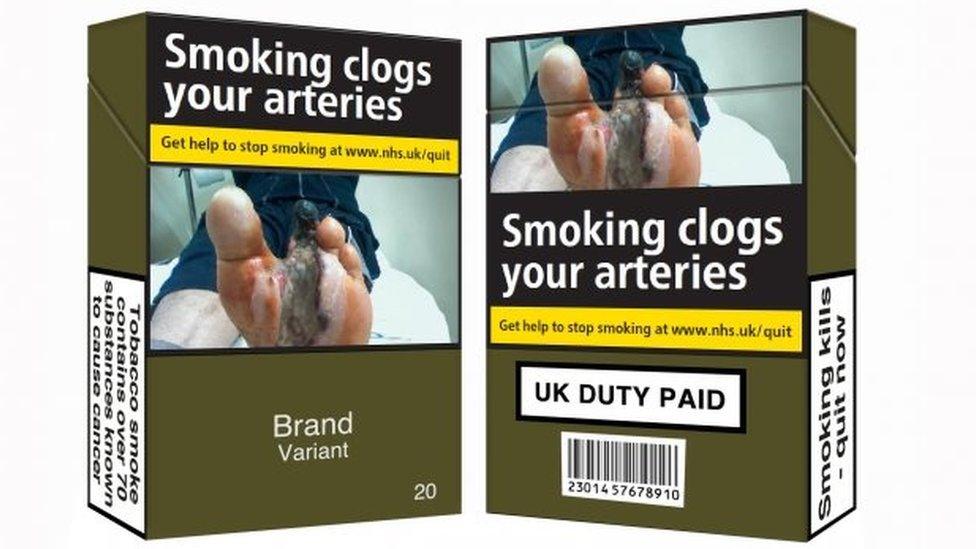

But the Conservatives have continued to crack down on tobacco

Dolly Theis, a Conservative candidate at last year's general election, and a policy expert in public health, says that far from restricting freedom of choice, the government's childhood obesity strategy, which aims to ban the sale of fatty and sugary foods at supermarket checkouts among other things, is about increasing choice.

Few people decide "I want to be obese" but their choices can be limited by their economic circumstances, she says.

"By the age of five, children in poverty are twice as likely to be obese as their least deprived peers, and by the age of 11 they are three times as likely," she wrote in a paper for the Bright Blue think tank. , external

"They are also more likely to live in an area with more takeaway and fast food outlets; more likely to live in poor, unsuitable or overcrowded housing; and more likely to experience a combination of family breakdown, stress, mental health issues and financial problems - all factors which can impair parents' ability to make rational and compassionate decisions."

The childhood obesity strategy, she claims, marks a significant shift "away from viewing childhood obesity as an issue of poor personal choice, towards understanding that our environment, socioeconomic circumstances, education and the influence of the food and drinks industry, dictate the choices we are presented with".

Cutting obesity will also save the NHS millions in the longer term, reducing the need to increase taxes - another key Conservative priority, she adds.

But cabinet tensions over how far the government should go in its efforts to improve public health, and what tone it should adopt, suggests the debate in the party is far from settled.