Reality Check: Red lines on the Irish border

- Published

The Irish prime minister is in Brussels on Thursday to meet EU leaders - a reminder that Ireland is centre stage in the Brexit negotiations.

When you boil Brexit down, a lot of it is about borders.

And as the sound and fury of the Brexit debate at party conferences begins to fade, one fact remains - progress needs to be made on the complex issue of the Irish border in the next two weeks.

So with deadlines fast approaching, and fundamental issues at stake, it's not surprising that the rhetoric is being ramped up.

Are we back to red lines? We are.

"There's only ever been one red line," the leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, Arlene Foster, told BBC news, "and it is this, there cannot ever be a border down the Irish Sea, a differential between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK."

"The red line," she added, for the avoidance of any doubt, "is blood red - it's very red."

UK Prime Minister Theresa May is dependent on the support of the DUP for her wafer thin majority in the House of Commons, so the party's position matters more than usual.

But while it might appear that positions are hardening, there are some signs that the outlines of a possible deal could soon emerge.

Will all sides accept it? Be prepared for a rollercoaster ride.

Why is Ireland such a complicated issue?

Once the UK leaves the European Union (yes, I know there are still plenty of people campaigning to prevent that) the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland will be the only land border between the UK and the EU.

The EU position is that Brexit will create some friction in trade.

And as both sides have agreed that there will be no border checks or infrastructure of any kind at the Irish land border, you then have to decide where that friction occurs.

The EU argues that it has to be, in some form, between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which brings us to the Irish Sea - and the backstop.

Remind me what the backstop is

It is part of the proposed withdrawal agreement between the UK and the EU, a legal text designed to ensure, in all circumstances, that no hard border emerges between Northern Ireland and the Republic.

Both sides hope they can achieve that anyway in a future agreement on a new trading relationship after Brexit. But if there were to be a delay or a failure in reaching such an agreement, the backstop would kick in automatically.

The trouble is the two sides can't agree on what the backstop text should say.

The EU has produced a draft text that would keep Northern Ireland in the EU's customs territory and in parts of the single market dealing with goods and agriculture.

The UK says that is unacceptable. It wants the customs part of the backstop to be UK-wide. But it has now signalled that it is, in the words of the Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab, "open to looking at some of the options on regulatory checks".

For the EU that means some kind of checks between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The UK government appears to be moving in that direction - but it still needs to carry the DUP, and the Conservative Party, with it.

What kind of checks are we talking about?

Broadly, the checks that need to take place for goods entering the EU single market (or the UK market for that matter) can be broken down into four categories:

customs

VAT

regulatory checks on product standards

sanitary checks on food, animals and plants (known in the jargon as SPS or sanitary and phytosanitary checks)

Carrying out checks doesn't necessarily mean that you are creating a border, though. EU officials point out that there are VAT checks between the Canary Islands and the Spanish mainland and no-one sees that as a threat to sovereignty.

But they also acknowledge that history and politics makes Northern Ireland a special case.

That is why the EU's chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, said recently that he wanted to "de-dramatise" the backstop, and the border issue more generally. If it can be turned into an issue of practicality, rather than an issue of sovereignty, then it should be easier for progress to be made.

What does de-dramatise mean?

Whatever you do, don't call it a border.

Mr Barnier has said that many checks on products moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland could take place at factories or elsewhere in the supply chain. Similarly, most customs checks could take place online, to be followed by barcode scanning in transit - on ferries perhaps, or elsewhere.

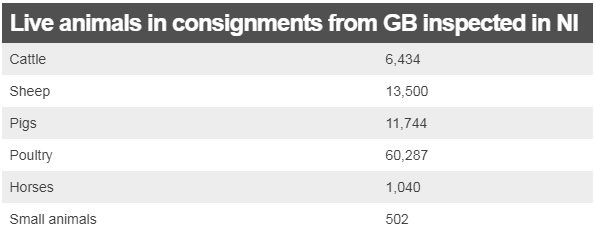

The only checks that would, under EU law, have to take place on entry into Northern Ireland would be those on food and animals. And that already happens to some extent. Consignments of live animals are checked for health and animal welfare standards at the port of Larne on arrival from Great Britain.

Source: DAERA - for year ending 31 August 2018

The number of checks would have to be increased significantly: it would have to include all food produce, because food standards in Northern Ireland would have to be the same as EU standards. But the distinction between borders and checks could be important. "No border" down the Irish Sea, says the DUP very firmly and the prime minister agrees. But the government could argue that additional checks would not break that promise.

There would certainly be technical questions about how some of those checks would work in practice and about who would police the system if there was disagreement. But, with a certain amount of goodwill, it might just work.

Never mind checks, what about Chequers?

Where do the government's plans fit into all of this?

The government argues that its Chequers proposals would solve issues surrounding the Irish border in the long term. If a political declaration accompanying the withdrawal agreement reflected that, it would serve as reassurance that the backstop would never have to be triggered.

But the "Chuck Chequers" faction of the Conservative Party, which wants a "clean break" Brexit, is furious, while the EU has, for very different reasons, rejected the main economic proposals that the Chequers plan contains.

So, it needs to be reworked. One suggestion is that the whole of the UK could stay in a temporary customs arrangement (don't call it a union) with the EU for some time after Brexit. Another is that the UK would strengthen its proposed alignment with EU rules in the future. Even that may not be enough to satisfy leaders in Berlin, Paris and Brussels but it would be certain to infuriate "clean break" Tories still further.

The backstop remains in play then?

It does yes and one of the implications of treating Northern Ireland differently is especially problematic. Any future free trade deals around the world would, in theory, have to be signed on behalf of Great Britain and not the United Kingdom. Northern Ireland would be aligned with EU regulations on goods, for example, and would have to be excluded.

That takes us back to the DUP's "blood red" lines.

"There cannot be any new regulations," Arlene Foster insisted, "because that would prevent us in, say five or 10 years' time, when the UK is involved in a fabulous trade deal… Northern Ireland wouldn't be able to be a part of that trade deal if there were those new regulations."

The obvious answer is to find a solution that works for the whole of the UK. But no one can agree on what that solution should be.

So it's still mind-bogglingly complicated?

Yes - and that is hardly surprising given what is at stake.

The big problem, even with an amended version of Chequers and a new text for the Irish backstop, is this: can it convince enough Tory backbenchers, can it convince the DUP, and can it convince the rest of the EU? On that, the jury is still out.

It's certainly possible to imagine compromise language - a fudge, if you will, that will keep the Brexit negotiations moving forward in the next few weeks. But apparently irresistible forces are still on course to meet what appear to be immovable objects.

Something will have to give.