Brexit and the booming British strawberry

- Published

British consumers are eating more than twice as many strawberries as they did 20 years ago. A big part of the reason for this, say farmers, is the army of East European workers flown in each year to pick them, which has helped keep prices down. What's going to happen after Brexit?

Not so long ago you could only buy British strawberries in June and July. They were a treat to be enjoyed during Wimbledon.

Now thanks to modern cultivation techniques they can be grown from April to October, and the UK is close to self-sufficient in strawberries during those months. Britain's seemingly ever-growing appetite for strawberries is sated by imports from Spain, Israel, Morocco and Egypt during the rest of the year.

The industry makes no bones about the fact that the dramatic increase in the production and consumption of strawberries, and other soft fruits, would not have been possible without imported EU labour, most recently from Bulgaria and Romania, who make up 99% of their workforce.

It has kept prices down - a 400g punnet of mid-season British strawberries has cost around £2 for more than 20 years.

But the good times may soon be over for the industry, as Brexit threatens to restrict the supply of workers it relies on.

British farmers have been using foreign labour in ever growing numbers since 1945, when the first seasonal agricultural workers scheme was launched, as a student exchange programme.

The scheme was scrapped in 2013, with the coalition government arguing that the there was enough labour from new EU countries like Romania and Bulgaria to fulfil the industry's needs.

But the UK's post-Brexit immigration rules are likely to dramatically cut back on unskilled EU migration.

Until recently, the number of foreign seasonal agricultural workers coming to the UK from other EU nations for a few months each year was roughly equivalent in size to the British army - 80,000.

About 30,000 of those were put to work harvesting soft fruits and berries.

But like the army, there has been a recruitment problem of late. Falling unemployment in Romania, coupled with a fall in the value of the pound, has made a summer toiling on British farms, and living in barracks, suddenly seem far less attractive.

Farms say they are struggling to recruit enough workers to harvest their crops, leading to claims of fruit and vegetables being left to rot in the ground.

The UK government has launched a pilot scheme to encourage non-EU workers, from places like Moldova and Ukraine, to take temporary work on British farms.

But the 2,500 annual quota for these workers has been branded a "drop in the ocean" by farmers.

Strawberry fields forever?

Polytunnels have extended the growing season on British fruit farms

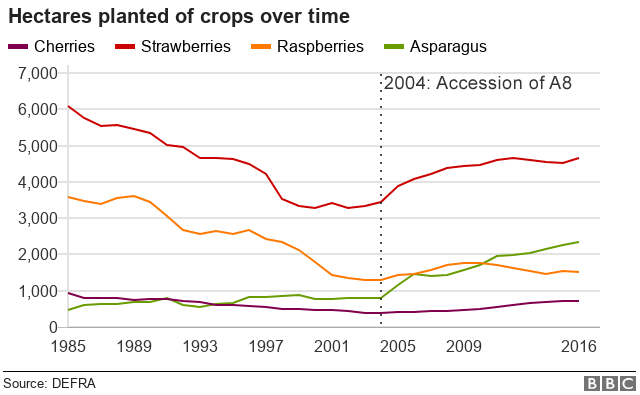

In 1996, British consumers ate 67,000 tonnes of strawberries and 13,000 tonnes of raspberries

In 2015, strawberry consumption was 168,000 tonnes - an increase of 150%, with 70% of them grown in the UK

Raspberry consumption increased by 123% to 29,000 tonnes over the same period with around 60% grown in the UK

Consumption of other berries - including blackberries, blueberries and gooseberries - went up from 12,000 tonnes to 50,000 tonnes, with 80% of them imported

Source: Defra

Their mood was hardly improved by comments last week by the government's chief immigration adviser, Alan Manning, who told a committee of MPs it would not be the "end of the earth" if the fruit and vegetable sector in the UK shrunk after Brexit.

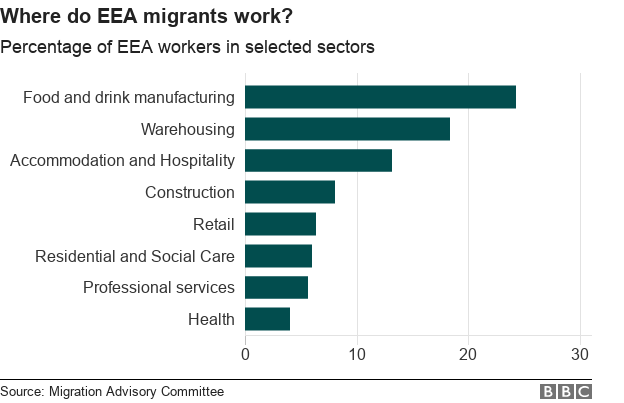

Horticulture is not the kind of high-skilled, high productivity industry the government has been targeting. Mr Manning argues that the industry, like others that rely on foreign workers, has had a "fair wind" from EU free movement and it was time it paid something in return for its "privileged" access to cheap labour.

His Migration Advisory Committee suggested forcing farmers to pay a higher minimum wage to encourage greater productivity, in a recent report, external.

How they used to do it: Strawberry pickers enjoy a break on a Hampshire farm in 1900

National Farmers Union President Minette Batters said: "The extraordinary success of the UK's fruit and vegetable sector shows how innovative British farming can be - the public have benefited with a plentiful supply of high-quality iconic crops such as strawberries, raspberries, apples, asparagus and many other seasonal crops, as never before.

"It may not be the 'end of the earth' to Mr Manning if this labour was lost but it would certainly have very negative impacts for the public and would be devastating for the businesses that produce them."

Farmers argue that growing fruit and vegetables close to market helps the environment, because they don't have to be trucked across Europe to get to British shops.

They also claim, in a recent report by British Summer Fruits, external, that the price of strawberries will increase by 50% if shops are forced rely solely on imports - something they fear will happen if the government does not make an exception for unskilled seasonal workers in its post-Brexit immigration regime.

"The NFU has long maintained that British farmers should not be left at a disadvantage to their competitors post-Brexit," says Ms Batters.

"The majority of EU countries and developed economies recognise the importance of seasonal work for home-produced food and have schemes that enable access to an essential workforce."

The Migration Advisory Committee is a bit less gloomy, predicting "modestly higher prices" in the shops and the closure of some farming businesses.

One thing that almost certainly won't be happening after Brexit is a recruitment drive for British fruit pickers.

"There are a limited number of people within the UK who are either available or wish to do seasonal work," says Nick Marston, chairman of British Summer Fruits.

He concedes that fruit picking "has got an image problem within the UK workforce" but he denies claims it is the relatively low wages, early starts and backbreaking work that is putting people off.

"Brits are not lazy. British people prefer to work indoors with a roof over their head, in a coffee shop or a retail outlet, rather than in a field. They want a full-time job. It's the same all over the Western world."

There was a time, of course, when all harvesting was done by the local population, but people have drifted away from the land and the parlous state of public transport in rural areas makes working on a farm all but impossible for many.

In the long run, the debate might become irrelevant as machines take over from humans on Britain's farms.

But, says Nick Marston, this is not likely to happen for another 10 to 15 years.

"It is the most difficult job you can ask a robot to do, go into a field and pick strawberries or raspberries."

For now, the industry is hoping the government will listen to its pleas when it unveils its long-awaited Immigration Bill, setting out post-Brexit immigration rules.