Budget 2018: Your essential trivia guide

- Published

It's Budget day on Monday, which is either a treasured Parliamentary tradition or - in the words of former Tory prime minister Harold Macmillan - "a bit of a bore".

All eyes will be on the nation's economy and the year ahead, and there's always plenty of speculation about what will or won't be announced.

So while we wait for Philip Hammond to lay it all out, here are some handy Budget trivia to warm up with.

It's a Monday

Not much of an observation, you might think, but this Budget is somewhat of an outlier.

It's the first one to be held on a Monday since 1962 when the chancellor was one Selwyn Lloyd.

Philip Hammond will be hoping to fare better than Lloyd, who, after increasing tax on ice cream and sweets, was accused of taxing children's pocket money and sacked a few months later.

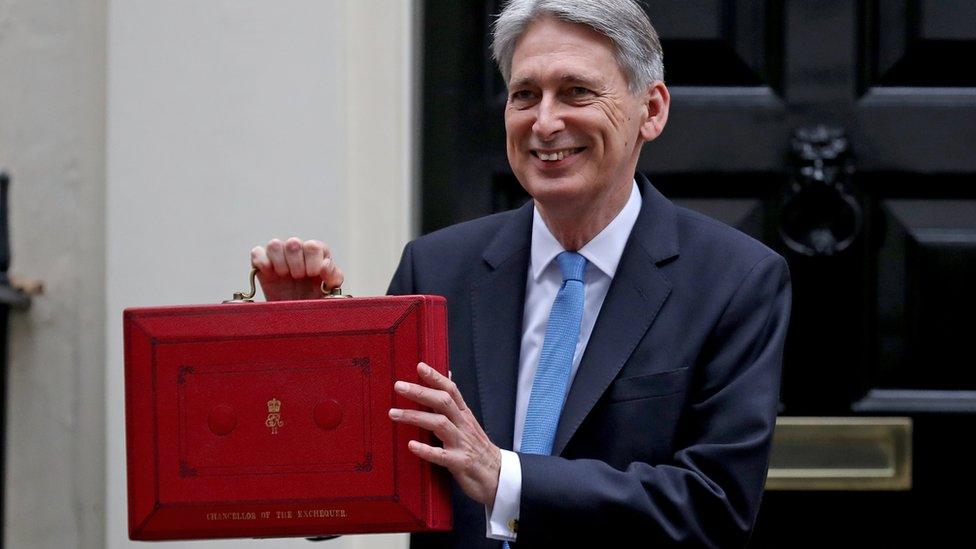

The photo-op

Presentation is a big factor in the Budget. When Conservative Nigel Lawson became chancellor in 1983 Margaret Thatcher, never one to mince her words, bluntly told him to get a haircut - a neat and tidy chop she hoped would be emblematic of a neat and tidy economy.

The defining image of every Budget is the chancellor standing outside No 11 Downing Street holding up his red box - used to transport his speech - in front of jostling photographers.

This will definitely happen

Mr Hammond uses a red box handcrafted by official providers Barrow Hepburn & Gale, but before 2011 the vast majority of chancellors would raise the exact, if rather withered, box first held aloft by William Gladstone in 1860.

One exception was Labour's Gordon Brown who entrusted four engineering apprentices in Scotland to build a box for him. All the young trainees had no idea of the box's purpose or its new owner.

Speaker switch

Regular Commons-watchers are used to hearing the loquacious interjections of Speaker John Bercow but for Budgets he vacates the chair to be replaced by his deputy Sir Lindsay Hoyle.

This tradition dates back to the late 17th Century when the Speaker of the House of Commons was in the unenviable position of representing both Parliament and the King's interests. As such, when debating tax - that may relate to the King - MPs needed their "own man" not the man they saw as the King's spy.

It means the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee (the senior deputy speaker) fills in.

The speech itself

For each of Mr Hammond's last two Budgets, he spoke for about an hour - a far cry from Benjamin Disraeli's five-hour speech in 1852 which included a break to rest the vocal cords.

Most of the policy announcements in the speech will have been carefully cultivated, with interested parties consulted months previously. Few, if any policies will be thrown in at the last moment.

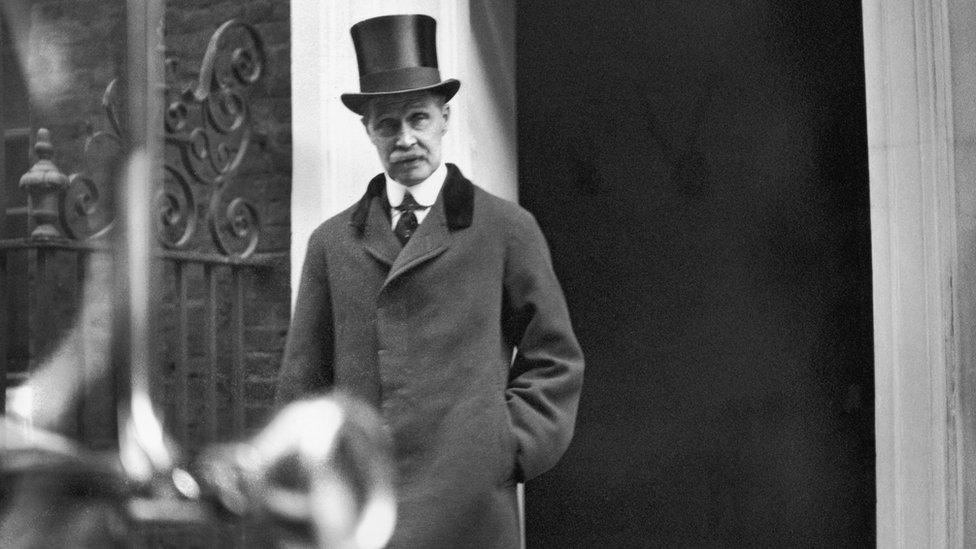

Andrew Bonar Law unsuccessfully tried taxing dogs

One exception came in the 1917 Budget when Andrew Bonar Law surprised the nation by announcing a tax on dogs. This was thought to be in response to a committee report criticising the drain on national food resources from dog food, published only a day before.

This policy was later shelved.

For Denis Healey, Labour chancellor in the 1970s, the most enjoyable aspect of the speech was finishing it.

He said: "On the whole, the great thing was to get it over and to be able to relax on the Wednesday and think, 'Well, now I don't face this particular problem for another 12 months.'"

The votes

The Budget speech itself is just one aspect of the whole process. Changes to existing taxes often come into effect that evening but new tax measures are debated over a four-day period in the House over the following days with MPs choosing to accept or reject what's in front of them.

This is the means by which the DUP could, as they have threatened, block the Budget by voting against it.

Separately, a Finance Bill - which legally enacts any changes announced by the chancellor - is introduced for consideration by MPs.

Though the contents are seldom changed, in 1994 the then Conservative Chancellor Ken Clarke was forced to abandon his plan to increase fuel duty after the House rejected it.

The House of Lords, meanwhile, has little role in the whole process.

After they created a constitutional crisis when they attempted to block the 1909 People's Budget, their right to have a say on money bills was removed by the 1911 Parliament Act.

Beware the backlash

George Osborne's attempt to add VAT to hot baked goods went down badly

Often the success of a Budget can hinge not just on the policies themselves but the reaction to them. Bad next-day headlines or a catchy phrase for a particularly pernicious tax can fatally undermine a chancellor's authority.

In 2012, the infamous "pasty tax" where VAT was imposed on hot baked goods forced George Osborne into an embarrassing U-turn while, back in 1932, the Times condemned Neville Chamberlain's Budget for its "puritanical severity".

For the opposition, an attack line or damning critique after the speech is vital.

William Hague, who as Conservative leader of the opposition had to respond to the Budget, once labelled Gordon Brown the "pickpocket chancellor" and the man in the pub who says "lend us a fiver and then I'll buy you a drink".

Moreover, Arthur Ponsonby, one-time Labour MP and peer, said of the Conservatives' 1925 budget: "Churchill's sympathy for the poor was eloquent but his sympathy for the rich was practical."

Philip Hammond will be hoping to avoid such stinging soundbites when he sits down on Monday.