Budget 2018: Do the poor benefit the most from the Budget?

- Published

The claim: People on the lowest incomes benefit most from Monday's Budget.

Reality Check verdict: The Treasury has not published analysis of whether this Budget will help the richest or poorest the most. The Institute for Fiscal Studies says the poorest will benefit the most as a proportion of their income. The Treasury's analysis of Budgets since 2016 suggests the poorest would do better, but its analysis of Budgets since 2015 suggests that the poorest will benefit less than many richer people.

Much of the debate following the Budget on Monday has been about whether the measures announced will disproportionally favour people with high incomes.

Chancellor Philip Hammond told BBC Radio 4's Today Programme that in fact it's the people on the lowest incomes who would proportionally benefit the most from the measures he announced, pointing out that he had put an extra £6.5bn into Universal Credit.

The analysis published by the Treasury does not allow us to establish whether that is true for this Budget.

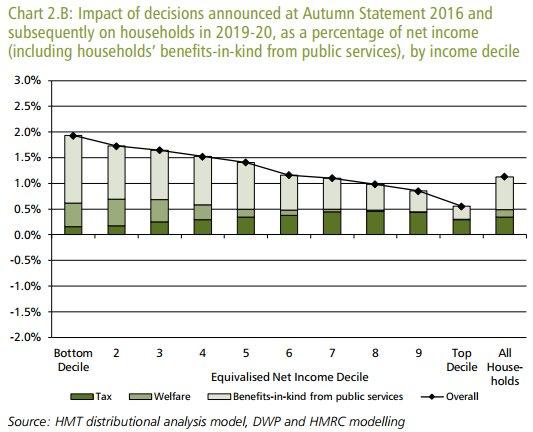

The relevant chart, external in the Budget documents does not just look at Monday's Budget - it combines the impact of all the measures since the Autumn Statement in 2016. The Reality Check team asked the Treasury for the analysis of just Monday's Budget but was told it was not available.

The chart divides the population into 10 equal groups and ranks them from the lowest income on the left to the highest on the right.

The chart does indeed show that the poorest people are benefiting the most.

This Treasury analysis does not just consider the value of changes to taxes and benefits - it also puts a cash value on the public services to which households have access. So, for example, the increased spending on the NHS will be counted as an increase in the value of services people get and hence a benefit from the Budget.

Because public services are worth more to poor people in percentage terms than rich people, including benefits-in-kind automatically makes Budgets look more progressive.

But that is not necessarily what people are thinking about when they ask whether the poorest people are going to benefit most from the Budget.

Nonetheless, while the Treasury cannot provide figures to support the chancellor's claim about this week's Budget, if you include benefits-in-kind it may well be the case that the poorest people benefited most.

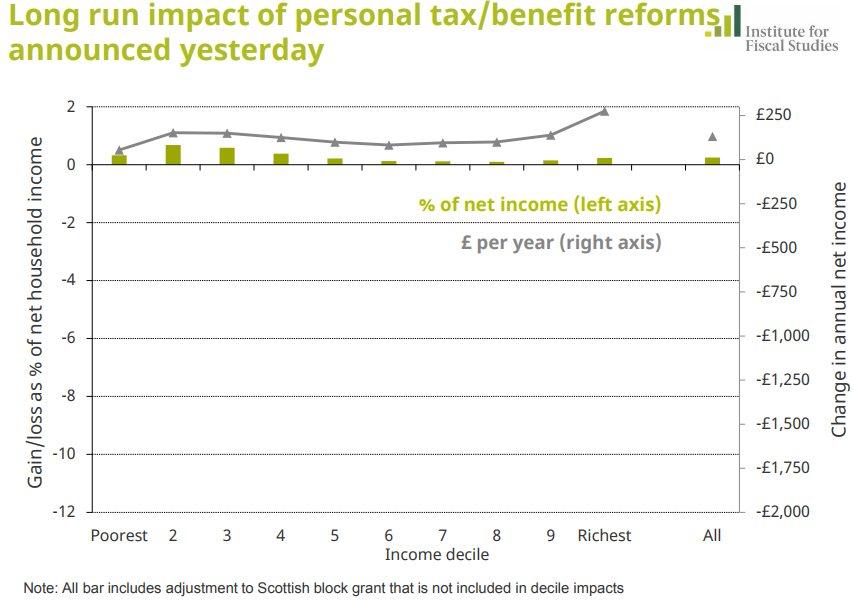

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) looked at the impact of Monday's Budget alone, external, not including benefits-in-kind, and found that as a proportion of income it would be poorer households that would benefit the most.

But the Resolution Foundation published similar analysis, external that suggested households with the highest incomes gained the most while the poorest gained less.

It said that while the poorest would benefit from increases to Universal Credit, higher income households would benefit to a greater extent from the rising amounts that may be earned before income tax needs to be paid.

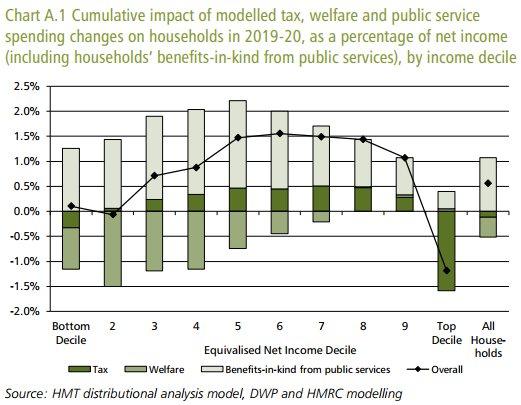

The Treasury analysis started with the Autumn Statement 2016 because that was Philip Hammond's first Budget. It may be argued that it would make more sense to go back to 2015, because that was when measures such as the four-year freeze to working-age benefits and the two-child limit for benefits were announced.

The Treasury does indeed publish this analysis, including measures that were announced before 2015, but implemented after then. It still includes benefits-in-kind from public services.

This analysis finds that the 10% of households with the highest incomes lost the most, followed by the 20% of households with the lowest incomes.

Going back to 2015 makes the changes look considerably less progressive than starting in 2016.

- Published30 October 2018

- Published30 October 2018