How John Bercow keeps Keith Vaz's secrets

- Published

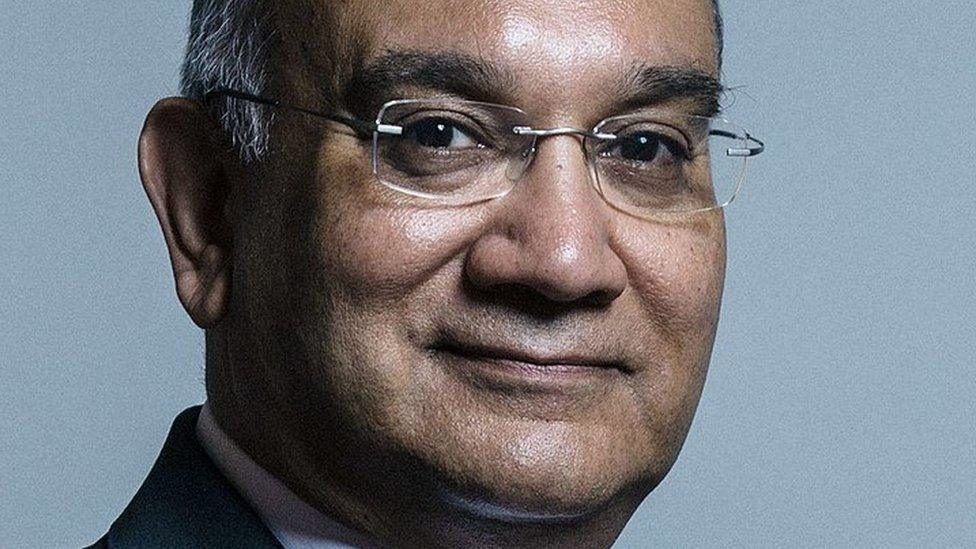

Keith Vaz MP has denied allegations of misbehaviour

In the 17th century, England had a problem with laws on sedition. MPs could not speak freely about the king's policies for fear of judges. To solve that problem, we adopted a special guard against tyranny: "parliamentary privilege". Now, John Bercow, speaker of the House of Commons, has invoked it to stop Newsnight getting information about the behaviour of the MP Keith Vaz.

Readers may recall that we have reported extensively on how Mr Vaz's behaviour on committee trips abroad, paid for by the taxpayer, were the scene for some allegations of not following the rules of the House and bullying towards staff.

Mr Vaz denies all such actions. But we wished to see what documentation existed from the administration of these trips. We cannot.

This is because Mr Bercow has personally intervened and gone out of his way to bar Newsnight from asking the Information Commissioner or a judge to review the decision. We will not be able to overturn this decision, as journalists fought through the courts to get to see MPs' expenses.

The core legal text here is the 1689 Bill of Rights. It states: "the Freedome of Speech and Debates or Proceedings in Parlyament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any Court or Place out of Parlyament."

The two Houses in Parliament should have what lawyers refer to as "exclusive cognizance" over their own affairs. Judges may not interfere in what parliament does.

This is perhaps the most important legal change in England that came from the 1688-9 coup, dubbed by supporters "the Glorious Revolution", when James II was replaced by the Dutch prince William of Orange and his wife Princess Mary. It is an important constitutional principle.

That is why MPs and peers can make allegations in the Commons or Lords without fear of libel law. When Lord Hain named Sir Philip Green as having obtained an injunction against the Daily Telegraph, he was deploying this right. Injunctions have no weight inside the walls of the debating chambers.

Lord Hain said the details were "clearly in the public interest"

The current legal position is that this privilege covers "proceedings". So members taking part by speaking in a debate or "voting, giving notice of a motion, or presenting a petition or report from a committee..." are protected by privilege.

But it does not cover everything parliament does. And where there is a dispute between the courts and parliament, judges decide where to draw the lines.

For example, in 2010, the Supreme Court had to rule on whether the act of claiming parliamentary expenses was the sort of thing privilege should cover. If claiming expenses were a "proceeding" of the House that the Bill of Rights should cover, as some of the accused claimed, a prosecution could not be brought for dishonesty in a court.

But as one of the justices put it: "I am accordingly satisfied that the prosecution does not infringe article nine of the Bill of Rights by impeaching or questioning the freedom of speech, the freedom of debates or the freedom of proceedings of the House or of its Members."

Mr Bercow with the current Dutch monarch, King Willem-Alexander, and his wife, Queen Maxima. King Willem-Alexander is descended from a cousin of William III, whose seizure of the English throne led to the Bill of Rights.

That is why I was struck by a recent decision by Mr Bercow. We applied under the Freedom of Information Act to get papers relating to Mr Vaz's trips abroad.

Clerks raised concerns - denied by the Leicester MP - that Mr Vaz had not abided by all the rules for trips. We wanted to know if those concerns ever become formal complaints.

If they did, did the liaison committee, which controls this process, do anything about it? This is clearly an area where, one could argue, the Freedom of Information Act should bite.

If the administration of MPs' expenses is not covered by privilege, why should the administration of committee trips be? MPs are involved - but they oversaw expenses too. Could knowing which travel agent booked tickets for MPs be a route to power for a would-be tyrant? What is the threat to free speech?

Some months ago, Mr Bercow personally made the argument that this paperwork was all covered by privilege. But I looked forward to a tribunal when this could be tested.

A personal veto

Normally, this sort of determination can be referred to the Information Commissioner and then to the tribunals and courts to judge whether that finding is fair. My judgment is, if they did that, I had a reasonable chance of winning.

I suspect Mr Bercow agreed. That would explain why he has now used an unusual personal power to block any appeals.

This week, I was notified he has issued a "certificate" under section 34(3) of the Freedom of Information Act. This is, in effect, a personal release veto.

These sorts of vetos are supposed to be used sparingly - an emergency reserve power to guard sacred spaces if courts get it wrong.

That is because their use means I have no rights of appeal. The Information Commissioner's view is that, since the certificate is genuine, that is the the end of the matter. Any appeal to the tribunals will automatically be discarded. I can ask a judge to review his decision, but it would entail looking at a decision taken by a parliamentary officer. That would hit privilege from another direction.

The net result is that the Speaker, who denies bullying, has made an order to hide information about the behaviour of his close personal friend, Keith Vaz, a man who also denies bullying - supposedly to protect MPs' freedom of speech.

And then he has gone out of his way to use a personal veto to make sure no-one could even consider reviewing that questionable decision.

You can understand why staff are so suspicious about whether MPs will ever let themselves be judged by outsiders when it comes to bullying and harassment.