Why do broadcasters use College Green?

- Published

MPs say they now fear for their safety when they go to be interviewed by the media on a green opposite the Houses of Parliament. What is going on?

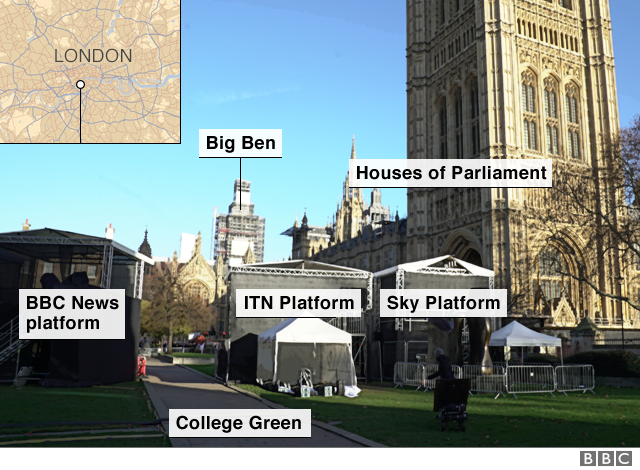

For decades now, College Green has been used as a venue for broadcast interviews.

For MPs, it has the advantage of being convenient - they simply have to stroll across the road from the House of Commons to be guaranteed a bigger audience for their views than they would ever get from speaking in the chamber.

For broadcasters, College Green provides the all-important sense of being at the heart the action, and gives them access to a steady stream of willing interviewees.

Anti-Brexit demonstrator Steve Bray talks to officers on College Green

It has traditionally been seen as a haven for backbenchers eager to get on the airwaves. Broadcast insiders call it the "honeypot" - MPs booked to do an interview by one outlet are collared by producers from rival outlets as soon as they come off air and ushered towards another microphone.

Some MPs and ministers prefer to be interviewed in the more controlled, and less muddy, environment of the TV studio.

Most broadcasters, including the BBC, have studios at Westminster, not far from College Green - where they can be interviewed "down the line" by presenters in another location.

College Green has traditionally tended to be pressed into action on big Parliamentary occasions such as budgets or general elections. On really big occasions, the main evening news bulletins will be presented from an elevated platform on College Green, offering a commanding view of the Palace of Westminster all lit up at night for added drama.

News presenters don't always have parliamentary passes, so hosting bulletins or news channel segments from within the building itself is not possible. But the extra space and freedom of the open-air studio makes the green a more desirable location anyway.

Pro-Brexit demonstrators are also making their voice heard

TV cameras were not allowed in the Commons chamber until 1989 - and broadcasters were allowed to film interviews with MPs in the building in only 2000, initially from a glass booth in the central lobby. Strict rules remain about where cameras can be placed.

Filming on the green gives broadcasters more control, as well as allowing guests without parliamentary passes to take part in live debates.

One thing the broadcasters can't control, of course, is what goes on in the back of their shots.

Interruptions by placard-waving protesters are an occupational hazard for anyone filming outside Parliament.

People have every right to stage protests - the roads and greens around Parliament are public rights of way - and, in normal times, there is little real friction.

Brexit has changed that dynamic, however.

The media has set up what is starting to feel like a permanent tented village, as the story continues to dominate the news bulletins. They might not broadcast from there every day but it has become a focal point for demonstrators.

The site is now ringed by metal barriers and the police have increased their presence.

The BBC has no plans to stop broadcasting from College Green but does not intend to report from there every day.

A BBC spokeswoman said: "We are working closely with authorities and other broadcasters to ensure the safety of our reporters and interviewees at all times."

The Parliamentary authorities have issued revised safety advice to MPs planning to take part in media interviews on the green.

Brexit protesters chant "Nazi and scum" at Conservative MP Anna Soubry

Most demonstrators - including the small group of anti-Brexit campaigners who set up their banners and flags outside Parliament every day and the pro-Brexit Leave Means Leave group who join them on occasions - are peaceful, although they have had occasional run-ins with the police and each other.

The most dogged of the anti-Brexit protesters, Steve Bray, engages in a daily game of cat and mouse with the broadcasters as he tries to get his slogan in shot.

In recent weeks, however, a more aggressive brand of demonstrators, from the pro-Brexit side, have started showing up to harangue and intimidate certain MPs as they make the short journey from the Commons to the green and back again.

Commons Speaker John Bercow has described them, in a letter to the Metropolitan Police, as a "regular coterie of burly white men who are effectively targeting and denouncing members whom they recognise and dislike - most notably female and those from ethnic minority backgrounds".

Journalists, such as the Guardian's Owen Jones, have also been targeted.

Sky News's Kay Burley says she has been interviewed three times by police investigating alleged incidents of abuse amid "the chaos that is College Green at the moment".

She told BBC Radio 5 Live she supported the right of people to protest but "it has become increasingly vile and aggressive and, yes, intimidating as well", specifically targeting anti-Brexit Conservative MP Anna Soubry, when she was on air.

More than 100 MPs have now called on the Metropolitan Police to do more to protect MPs - the police say they are ready to "deal robustly" with any instances of criminal harassment but they have to "strike a balance" that allows for protesters to exercise their democratic rights.

A recognisable figure in the group that surrounded Anna Soubry on Monday is online far-right campaigner James Goddard.

He says there can be no peace while Islam exists in the West and that the establishment is riven with paedophiles. He told police outside Parliament they were "fair game" and "if you want a war, we will give you a war".

Mr Goddard emerged as a DIY far-right campaigner last year as he began to gather followers after campaigning in support of the then-jailed anti-Islam activist, Stephen Lennon aka Tommy Robinson.

Before the incident at Parliament involving Ms Soubry, he'd been helping to organise France-style "yellow vest" protests - including attempts to block bridges in London.

Mr Goddard relies on donations from his followers - he frequently runs crowdfunding appeals for his campaigns.

On Tuesday evening, Facebook confirmed it has closed his account.

"We will not tolerate hate speech on Facebook which creates an environment of intimidation and which may provoke real-world violence," said a spokesman. Minutes later, his separate Paypal crowdfunding page disappeared too.

- Published8 January 2019