Why so many young women don't call themselves feminist

- Published

In recent years, feminist movements have attracted significant attention in Europe and North America. So why do so many young women still say they do not identify with the term?

Fewer than one in five young women would call themselves a feminist, polling in the UK, external and US suggests, external.

That might come as a surprise as feminism - the advocacy of women's rights on the grounds of equality of the sexes - has been in the spotlight lately.

A day after the inauguration of US President Donald Trump, millions around the world joined the 2017 Women's March. A key aim was to highlight women's rights, which many believed to be under threat.

Another defining moment came when sexual harassment claims were made against film producer Harvey Weinstein by more than 80 women - allegations he denies.

Online movements have also gained momentum. Actress Alyssa Milano suggested that anyone who had been "sexually harassed or assaulted" should reply to her Tweet with "#MeToo", resurrrecting a movement started by activist Tarana Burke in 2006.

Half a million responded in the first 24 hours and the hashtag has been used in more than 80 countries.

Jameela Jamil has been an advocate for body positivity

Many other celebrities have publicly embraced feminism, including actresses Emma Watson, who launched an equality campaign with the United Nations and "body positivity warrior" Jameela Jamil.

Movements like #everydaysexism and discussion points such as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Ted talk, We should all be feminists, external, have also struck a chord with millions.

Rejection of feminism

These events have all helped to bring feminism to mainstream attention.

So it is perhaps unexpected that the identity "feminist" has not gained more popularity among young women in the Western world.

In the UK there has been a small increase in the number of women who identify as such.

A 2018 YouGov poll found that 34% of women in the UK said "yes" when asked whether they were a feminist, external, up from 27% in 2013, external.

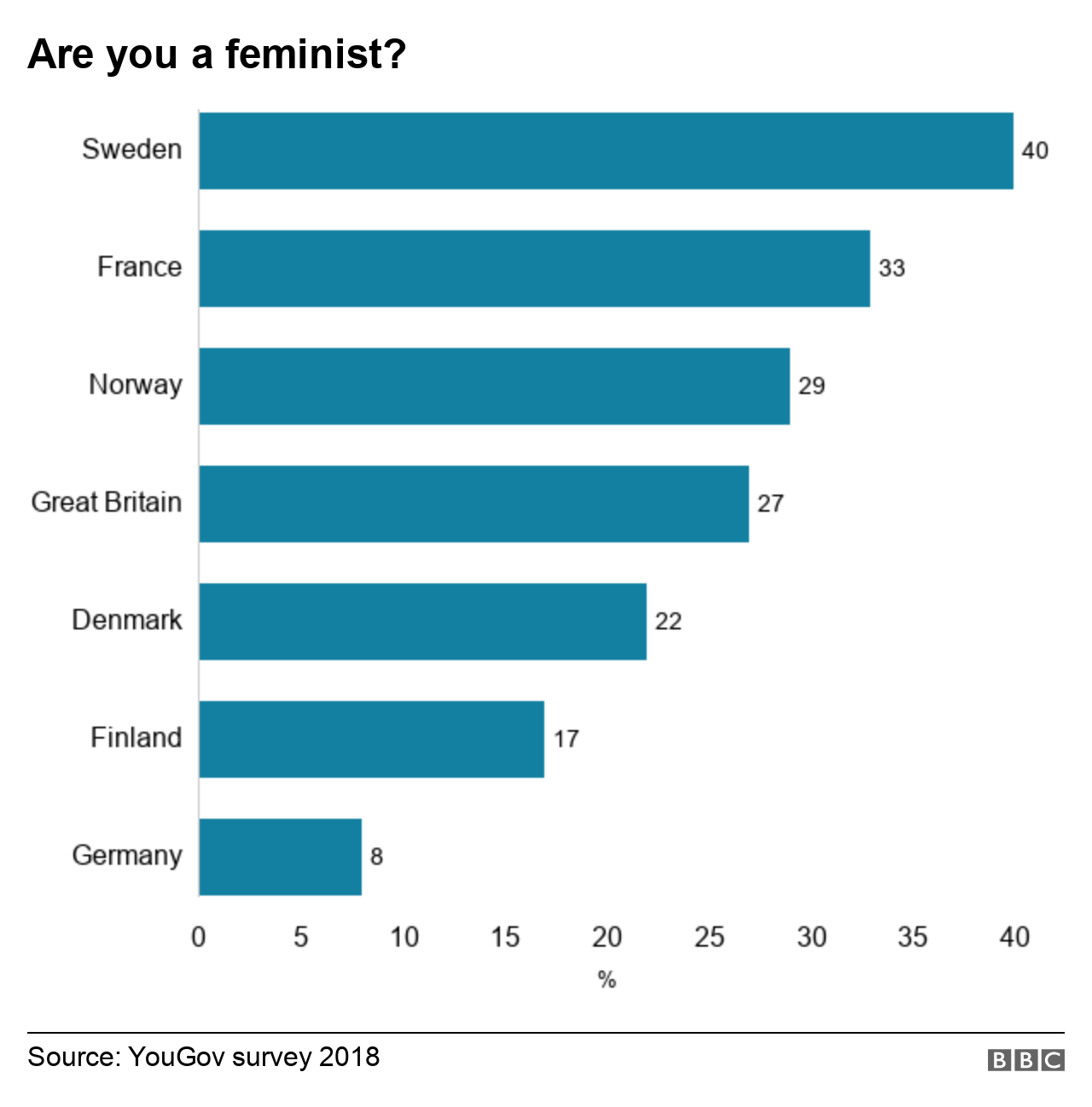

It's a similar picture in Europe, with fewer than half of men and women polled in five countries, external agreeing they were a feminist. This ranged from 8% of respondents in Germany, to 40% in Sweden.

However, people do not appear to reject the term feminism because they are against gender equality or believe it has been achieved.

The same study found that eight out of 10 people said men and women should be treated equally in every way, external, with many agreeing sexism is still an issue.

This appears to represent a shift in attitudes over time.

A study of 27,000 people in the US found that two-thirds believed in gender equality , externalin 2016, up from a quarter in 1977.

And in a 2017 UK poll, 8% said they agreed with traditional gender roles, external - that a man should earn money and a woman should stay at home - down from 43% in 1984.

If many believe gender equality is important, and still lacking, then why do relatively few people - including young women - identify as feminist?

It could be that they do not feel the term speaks to them.

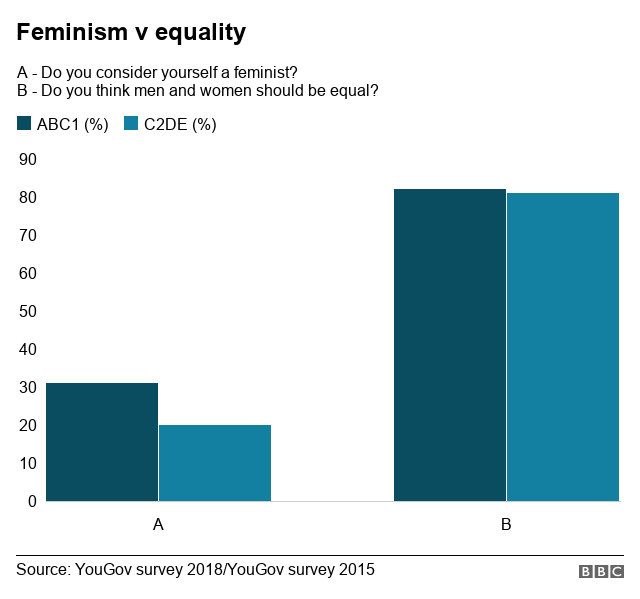

The term feminist is less likely to appeal to working-class women, polls suggest.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's TED talk "We should all be feminists" has been viewed more than 6 million times

Almost one in three people from the top social grade ABC1 - those in managerial, administrative and professional occupations - called themselves a feminist in a 2018 poll, external. This compared with one in five from grades C2DE, which include manual workers, state pensioners, casual workers, and the unemployed.

But those from lower income backgrounds are just as likely to support equal rights. Eight out of 10 people from both groups agreed men and women should be equal in every way, when asked for a 2015 poll, external.

This may suggest lower income groups support the principle behind feminism, but aren't keen on the word itself.

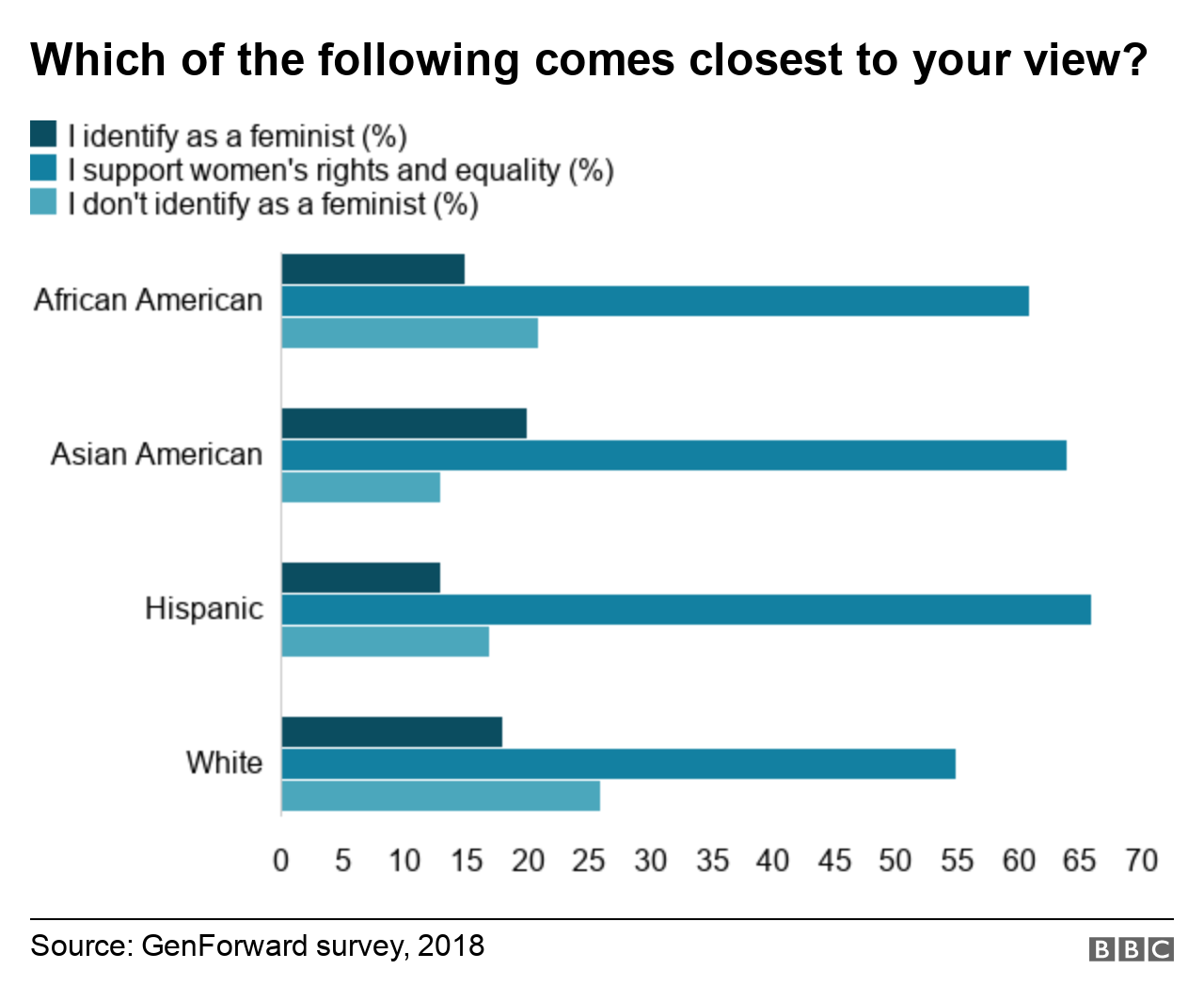

Race can also shape views of feminism.

Research into the views of US millennials, external found 12% of Hispanic women, 21% of African American women, 23% of Asian women and 26% of white women identify as a feminist.

Three-quarters of all the women polled said the feminist movement has done either "a lot" or "some" to improve the lives of white women.

However, just 60% said it had achieved much for women of other ethnicities - a sentiment shared by 46% of African American women.

Battling stereotypes

Another hurdle may be some of the stereotypes and misconceptions associated with feminism.

In her introduction to the recently published anthology Feminists Don't Wear Pink and Other Lies, curator Scarlett Curtis refers to the stereotype of feminists as not wearing make-up, or shaving their legs or liking boys.

These stereotypes have persisted through the ages. In the 1920s, feminists were often called spinsters and speculation about their sexual preferences was rife. Almost a century later, these views still hold some sway.

Having interviewed a diverse group of young German and British women for my research, external, I found associations of the term "feminism" with man-hating, lesbianism or lack of femininity was a key factor in rejections of the label "feminist".

The majority said they did not want to call themselves feminist because they feared they would be associated with these traits. This was despite many stressing they were not homophobic and some identifying as lesbian or bisexual.

So, how could the image of feminism be improved?

Arguably, as a society we should do more to challenge narrowly defined expectations of how women should look and act.

Working harder to make this movement more inclusive could mean that feminism speaks to the experiences and concerns of diverse groups of women.

Nevertheless, whichever label women choose to adopt, the indication that the vast majority of people now support equality - and acknowledge it has not yet been achieved - is heartening.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Christina Scharff, external is a senior lecturer in Culture, Media and Creative Industries at King's College London.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie