Nigel Farage: How election success brings Brexit crusader's career full circle

- Published

A serial loser in Westminster elections, Nigel Farage has now masterminded European victories with two different parties

The Brexit Party's success in the UK's European Parliamentary elections has put the seal on Nigel Farage's second coming in British politics.

It is a personal triumph for the veteran Eurosceptic and an apparent vindication - although his opponents will strongly disagree - of his claim that the public feels betrayed over the UK's failure to leave the EU.

The former UKIP leader will now head back to Brussels, where he has spent much of his political career, to resume his role as gadfly to Europe's elite.

How long he and his party's other MEPs get to spend there remains to be seen.

Yet with the three-year saga over the UK's departure from the EU seemingly not near a conclusion, there is no doubt he will make his presence felt.

The 55-year old has cut a distinct figure in the European Parliament since first being elected in 1999.

His tub-thumping, acerbic and often personal speeches - he famously once accused a senior EU official of having the "charisma of a damp rag" - have long been met with derision by the centre-left and conservative politicians who have dominated the chamber.

But he will find himself in friendlier company now, the ranks of MEPs from populist and nationalist parties hostile to much of what the EU stands for having grown.

It is quite a turnaround for a man who stood down as UKIP leader soon after the 2016 EU referendum, vowing to get "my life back".

Nigel Farage and Jean-Claude Juncker often spar in the European Parliament

But the consummate politician that he is, Mr Farage - who had earlier twice quit as UKIP leader before being persuaded to return - never really disappeared.

He found other controversial causes to embrace, both as a radio phone-in host and political disrupter.

He was early to anticipate Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 US presidential election and joined Mr Trump to celebrate it.

And after his bitter fallout with UKIP's new leader Gerard Batten over the party's association with far-right and anti-Islamic figures, it was only a matter of time before talk of a rival pro-Brexit movement came to reality.

Life's campaign

Whether Mr Farage's return to Brussels counts as a comeback or not, it undoubtedly brings his career full circle. Just as he has been doing for the past 25 years, he is still campaigning for the UK to leave the European Union, although this time he has warned there "will be no more mister nice guy".

If the UK is still a member of the bloc at the start of next year, he will find himself chalking up his fourth decade in the European Parliament - the irony of which will not be lost on anyone.

More than perhaps any other politician, it has been his lifetime's work to undermine an institution that has helped make his name.

He quit the Conservatives, whom he had supported since his school days, in the early 1990s in protest at what he saw as Prime Minister John Major's surrender over signing the Maastricht Treaty.

Nigel Farage left the Conservatives in the early 1990s and has seldom looked back

Since then, first with UKIP and now with the Brexit Party, he has been making the case for the UK to unravel its political relationship with Europe and return to a pure trading arrangement.

An age before the term Brexit was coined and when the idea of leaving the EU was a relatively niche pursuit, Mr Farage was banging the drum.

For much of that time, his arguments were breezily dismissed and his media opportunities were restricted to the occasional appearance on Sunday morning political programmes at election time. That all changed in 2009.

Amid the global financial crisis and MPs' expenses scandal, UKIP overtook Labour to come second in European polls. On the face of it, it was a marginal improvement on its surprise success in 2004, when it had won 12 seats and more than 15% of the vote.

But what was different this time was the political capital that the party and Mr Farage, who had taken over as leader from Roger Knapman in 2006, was able to make of it.

He was a different kind of UKIP leader. While he came from a relatively privileged background - his father was a stockbroker and he attended a leading public school, Dulwich College - he could not easily be dismissed as a pin-striped amateur, cranky libertarian or crusty zealot.

For more than 20 years, he had combined his political activities with a successful career in the City as a commodities trader and broker.

Populism and immigration

With his populist, media-friendly style - unlike most politicians he genuinely looks at ease with a pint and cigarette in his hand - he connected with Conservatives uncomfortable with David Cameron's attempted modernisation of the party and with disillusioned Labour voters.

His years touring the country and talking politics - he described "every pub as a Parliament" - brought him into contact more directly than any other frontline politician, while public concerns grew about the EU and the question of immigration.

His preoccupation with the issue for a decade or more and his choice of language remains controversial. He has been accused of scare-mongering, xenophobia and, by some, of inciting hatred.

Immigration has been Nigel Farage's most potent weapon on the campaign trail - but has left him open to claims of prejudice and xenophobia

Mr Farage has long argued that legitimate concerns about the impact of "open-door" immigration on white, working-class communities, their economic opportunities and cultural identities, have been ignored by the metropolitan elite.

But, during the final week of the 2016 referendum, he was criticised for posing in front of a billboard featuring a queue of mostly non-white migrants and refugees which suggested the UK was at "Breaking Point".

A few hours after the poster was unveiled, the news emerged that the Labour MP Jo Cox had been killed by a far-right terrorist.

Seven-time failure

Mr Farage's refusal to back down from expressing his opinions has won him the grudging admiration of many conservatives.

But it has also made him, for many, a toxic figure who his critics claim is thin-skinned and intolerant of criticism.

He was sidelined by the official Vote Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum, despite having done so much to bring it about, and had to resort to stunts like throwing fish into the Thames outside Parliament to get his message heard.

He played no part in the TV debates, despite generally being thought to have outpointed Liberal Democrat Nick Clegg in a one-off TV encounter on Europe in 2014.

His involvement with the Leave.EU campaign - which was fined for breaching electoral laws and is the subject of a police investigation - remains contentious.

And his financial links to businessman and friend Arron Banks in the year after the Brexit vote are now the subject of an investigation by the European Parliament.

While such questions were never likely to bother his Eurosceptic base, it is a different matter when it comes to the swing voters needed to win first-past-the-post Westminster elections.

His multiple failed attempts to get elected to the UK Parliament, starting in 1994, lend some weight to the argument that there is a ceiling on his political appeal.

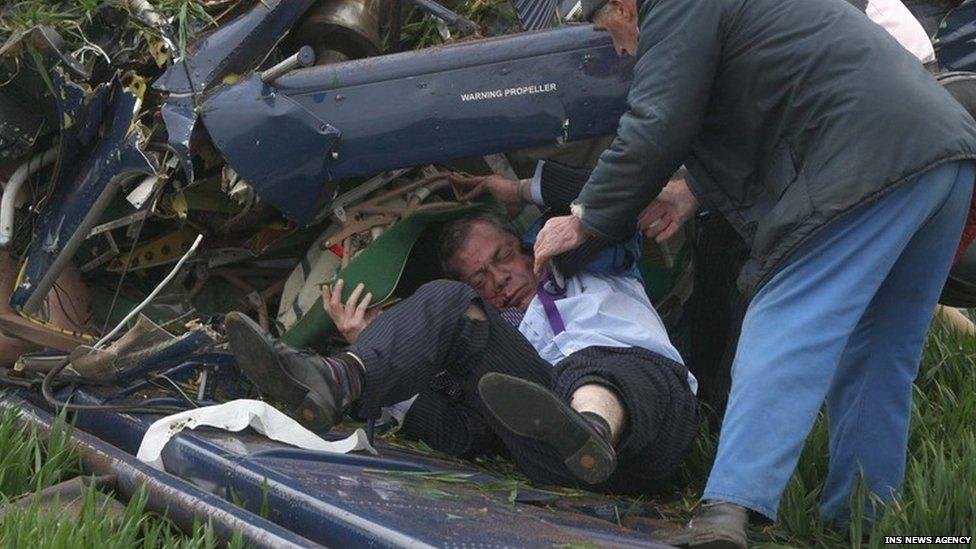

His unsuccessful 2010 campaign in Commons Speaker John Bercow's constituency is now best remembered for the light aircraft he was travelling in crashed in a field in Northamptonshire on polling day.

He fractured two vertebrae in his neck, broke several ribs and split his sternum in the accident. Despite a series of successful operations, he continues to bear the physical scars.

He broke two vertebrae and several ribs in a light aircraft crash on the day of the 2010 general election

Going into the 2015 election, UKIP saw its first MPs elected to Parliament in a series of by-elections. But despite being favourite to win the seat of Thanet South in his Kent backyard, he lost by just under 3,000 votes.

A serial loser in Westminster elections he may be, but this has freed him up to roam politically, rather than having to concern himself with the day-to-day responsibilities of a constituency MP - a role it has been suggested he would be ill-suited to.

Critics point to his poor voting record in Brussels, particularly when he was a member of the European Parliament's fisheries committee, as evidence that he is more interested in the political limelight than the hard graft of being an elected representative or holding a government to account.

His huge media profile - including more than 30 appearances alone on the BBC's Question Time - continues to irritate his political opponents.

Personal life

His crusading approach to politics has taken a toll on his private life. In 2017, he separated from Kirsten Mehr, a German government bond broker, after 20 years of marriage. Their two children are both fluent German speakers and have German passports.

He also has two children from a previous marriage to Irish nurse Clare Hayes, who cared for him following a serious accident in the mid-1980s when he was knocked down by a car and nearly lost a leg.

Less than 18 months after this accident, the then-21 year old discovered he had testicular cancer. In his 2015 autobiography Purple Revolution, he laid bare both his anger with the NHS for initially misdiagnosing his condition but also his gratitude for the ultimately successful treatment, which he says saved his life.

In the book, he claimed his three near-death encounters had made him more of a risk-taker.

Launching a new political party, albeit an extremely well-funded one, from scratch certainly constitutes a risk.

Where could it go from here?

Mr Farage remains young by the standards of other current party leaders, both in the UK and in the US.

For someone who has, in the past, seemed more interested in political arguments than power, he has even started talking again about breaking the two-party monopoly on British politics at the next general election.

This may be optimistic, at this stage, given that he has tried and fallen well short before.

But for the time being, Mr Farage is revelling in his status as the most talked-about, feared and, arguably, influential politician in the country.