Local elections: The main parties have been punished

- Published

The local election results are disappointing for both the Conservatives and for Labour, while the Liberal Democrats, Greens and independents prospered, writes Prof Sir John Curtice and colleagues on the BBC's local elections team.

"A plague on both your houses." That seems to have been the key message to emerge from the ballot boxes.

On the basis of the detailed voting figures in 40 local authorities, we estimate that if the pattern of voting in the local council elections were to be replicated across the whole of Great Britain, both the Conservatives and Labour would have won 28% of the vote. This is only the second time that this calculation has put both those parties below 30%.

The elections always looked set to be difficult for the Conservatives. The party was defending seats that were mostly last up for grabs four years ago, on the same day David Cameron won the 2015 general election. That, coupled with the party's recent freefall in the polls, clearly pointed to significant Conservative losses.

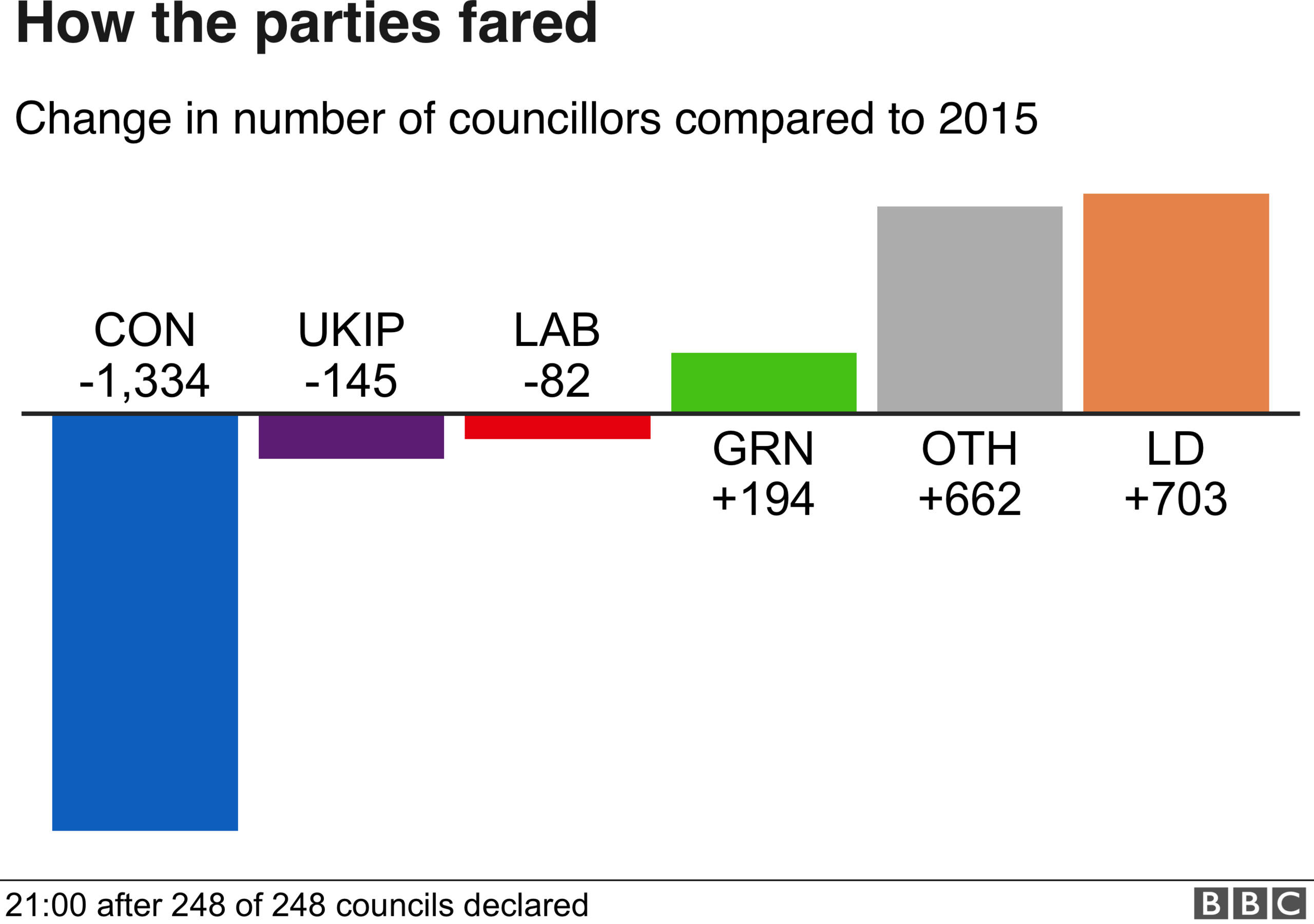

And that proved to be the case. The party has suffered net losses of more than 1300 seats. On average the party's share of the vote was down by six points, both compared with 2015 and with last year's local election results.

However, despite the government's difficulties, Labour also slipped back - on average, by no less than seven points compared with last year's local election results. As a result, the party has found itself suffering net losses of around 80 seats, when opposition parties are normally expected to post gains.

The party's performance would seem to confirm the message of a number of polls that Labour's support has been slipping in the wake of the Brexit impasse, a fall in Jeremy Corbyn's popularity, and a continuing row about anti-Semitism. Compared with last year, the party lost ground more heavily in Leave-voting areas than in Remain-voting ones, a pattern that it shared with the Conservatives (who in previous years have tended to perform better in such areas). This has been seized on by pro-Leave Labour MPs as evidence that the party should reach an agreement with the government which would pave the way for the UK to leave the EU.

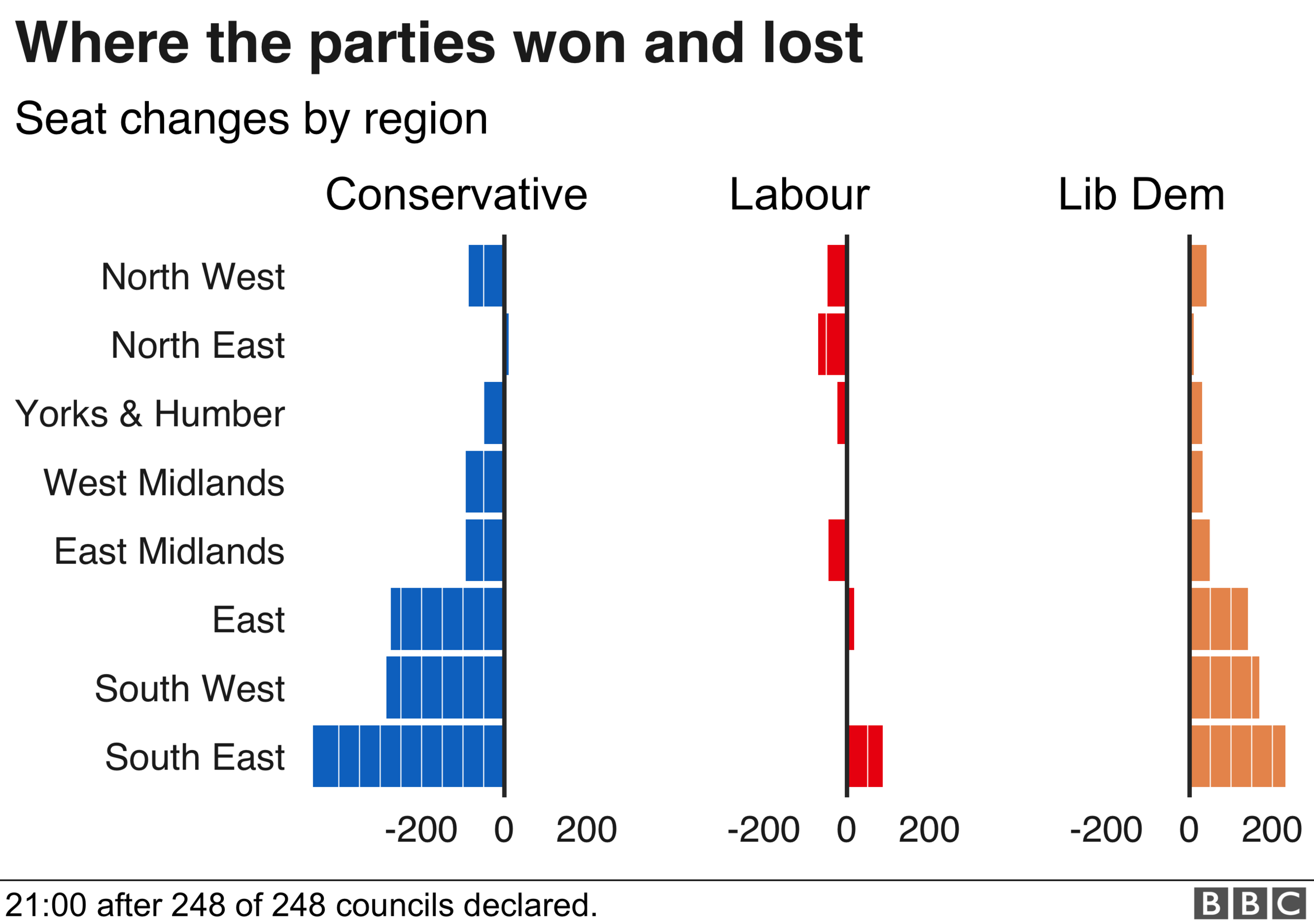

What the two parties also had in common was a tendency for their support to fall more heavily in their heartlands. Labour's vote fell back most heavily in the north, the Conservatives in the south. Equally, Labour's vote fell more heavily in wards where it was previously strong, while the Conservative vote fell most heavily where they were strongest.

It was as though voters vented their frustration with the Brexit process by punishing whichever party represented the political establishment locally.

This mood perhaps also helps account for the remarkable success of independent candidates. Those not standing on a party label were on average winning as much as a quarter of the vote where they stood. More than 900 independent councillors have been elected - a net gain of more than 500.

Meanwhile the Liberal Democrats, who before they entered into coalition with the Conservatives in 2010 were often a vehicle for protest votes, also appear to have profited from voters' disenchantment with the two largest parties.

The party, which has made net gains of more than 600 seats, advanced particularly strongly in Conservative-held wards where it was previously in second place. Double digit swings from the Conservatives to the Liberal Democrats were common in such seats. The party seemed to be successful in reinvigorating some of the bastions of local strength where its support had been badly eroded in the wake of the coalition government. This pattern added significantly to the tally of Conservative losses.

Theresa May insisted the local election results showed voters wanted the main parties to "get on" with Brexit.

In contrast, and despite the party's pro-Remain stance, there was only limited evidence that the Lib Dems' advance was stronger in areas that voted heavily for Remain in the 2016 referendum. For example, while support for the party rose on average by three points on last year in areas where more than half voted for Remain, it also increased by two points in areas where the Remain vote was less than 45%.

Thanks in part to the fact that in 2015 the Liberal Democrats had recorded its worst ever local election performance, the party was able to make so many gains, due to an increase in its vote since then, of eight points. More significant, perhaps, was the fact that its vote was also up by three points on last year's local elections.

When the party's performance is projected into a national vote, it is estimated to be worth 19% of the vote. This represents its best local election performance since the party entered into coalition in 2010, but was still well below the party's performance in any round of local votes between 1993 and 2010. Overall, the party's performance is best seen as evidence of a partial recovery from the depths to which the party sank during the coalition years.

At the same time, the Greens had one of their best local election results ever. The party made net gains of more than 180 seats. The Greens posted an average of 12% of the vote in the wards they contested, up five points on their performance where they stood four years ago. That equals the party's previous highest average, 12% in 2009, when local elections were held on the same day as European Parliament elections. The party may have been helped by the recent protests about climate change.

Fighting just one in six wards, there was little opportunity for UKIP to make much impact on these elections. Where it did stand, the party's vote was down by four points on its relative high point of 2015, but up eight points on its poor position last year. However, the challenge from the Eurosceptic parties may be more formidable in the European elections in three weeks time, when Nigel Farage's Brexit Party is on the ballot paper.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Sir John Curtice, external is professor of politics at Strathclyde University, senior fellow at NatCen Social Research, external and The UK in a Changing Europe, external. He is also chief commentator at WhatUKthinks.org, external.

He worked with Stephen Fisher, associate professor of political sociology, University of Oxford, external; Robert Ford, professor of politics, University of Manchester, external and Patrick English, associate lecturer in data analysis, University of Exeter, external.