Margaret Thatcher: How she confounded Tories who ridiculed idea of her as PM

- Published

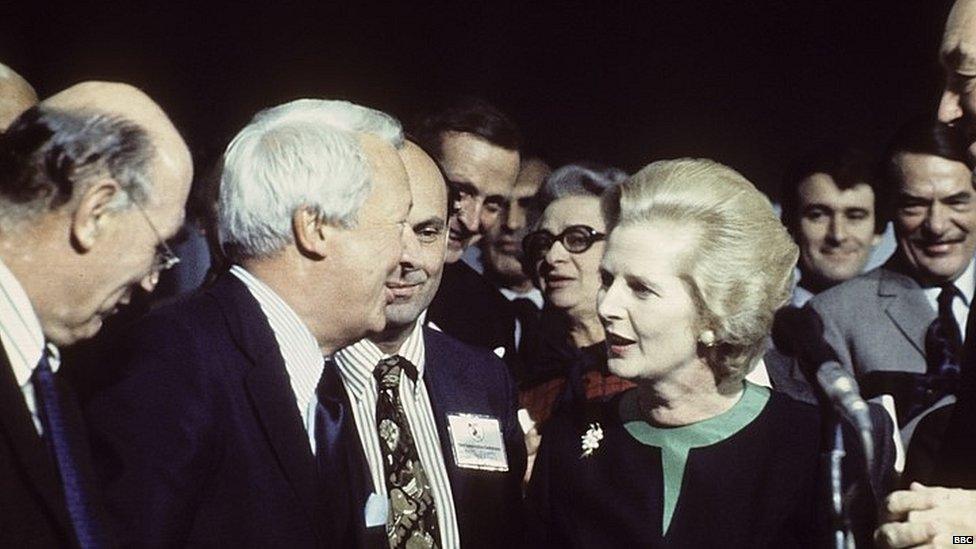

Margaret Thatcher, the UK's first woman prime minister, led the country between 1979 and 1990

The extent to which leading Conservatives under-estimated Margaret Thatcher, both as a politician and a woman, is laid bare in a new BBC Two series charting her rise to power.

Ken Clarke and Michael Heseltine, who went on to serve under the UK's first female prime minister, told Thatcher: A Very British Revolution that the idea of her one day leading the country seemed "incredible" to them back in the early 1970s.

"If you'd told me this woman would become prime minister, I mean no dislike of her at all, I'd have thought that was ridiculous," Mr Clarke told a documentary marking the 40th anniversary of Mrs Thatcher's first election victory in 1979.

Reflecting on Mrs Thatcher's rise to prominence and surprise election as Tory leader in 1975, Lord Heseltine said there were two sides to his colleague and political rival's character.

While she had a "fine mind", his view at the time was that "this was not a leader and not someone who was going to drive us to power".

Asked how he would describe the woman who went on to lead the country for more than 11 years, he said she came "from a certain social background, one step up the ladder of economic success, with it a lot of the characteristics that you associate with people who have just made it, a certain intolerance of those who haven't, a certain suspicion of those who are further up the ladder, a certain bigotry, slightly over-simplistic solutions about the nature of the society in which they live".

Margaret Thatcher's upbringing was rather different to most previous Conservative leaders

The Conservative grandee, who was a junior minister at the time and went on to challenge Mrs Thatcher for the Tory leadership in 1990, said there was one side to her personality "which conformed to type" and another "which had the intellect to rise way above it".

"You were wise to engage more seriously with the latter than the former."

Unlike aristocratic Tory leaders of the past, Mrs Thatcher grew up in a provincial English town - Grantham, Lincolnshire - with no inherited family wealth nor social connections. Her father Alfred ran two grocery shops, as well as being an alderman and Methodist preacher.

Former Conservative cabinet minister Lord Baker said her upbringing informed her economic and political thinking.

"To understand Margaret, you have to go back to Grantham. She lived in a very humble way. There are not many grocers' daughters who get to Somerville College Oxford to study chemistry," he said. "That required incredible drive and determination."

Mrs Thatcher, who died in 2013 at the age of 87, became only the second Conservative women cabinet minister in history when she was named education secretary in 1970.

Milk row

But, as former colleagues recall, her ministerial career was almost brought to a swift end by an explosive row over school spending cuts which led her to be dubbed the "milk snatcher" by the tabloid press.

During an "alcohol-fuelled" debate on the policy in the House of Commons, she was called "Attila the Hun and worse" by opposition MPs, Jonathan Aitken says.

"This one was like a sort of brawl," he remembers. "You couldn't hear her a lot of the time. She looked rather shaken - she was hurt."

Then-prime minister Ted Heath, who Mrs Thatcher went on to succeed as leader, had to be persuaded not to sack her from the cabinet, Mr Clarke recalls.

Ted Heath wanted to sack Margaret Thatcher from his cabinet but was persuaded not to

"He panicked about the fact that this secretary of state for education who he never liked anyway was now one of the most unpopular women in the country," Mr Clarke, who was a government whip at the time, says.

"In the whips office we all ferociously resisted. He can't do that. He could not sack the only woman in the cabinet. And on that basis, he reluctantly kept her."

Observers recount how Mrs Thatcher overcame her outsider status through a mixture of hard graft - she was, in Mr Clarke's words, a "highly intelligent workaholic" - and political calculation, enabling her to outmanoeuvre the Tory establishment and oust Mr Heath after his election defeats in 1974.

"She'd be too wordy, too worthy and she would try to get too much in," best-selling novelist and Tory peer Michael Dobbs says of her early Commons performances.

"But she worked incredibly hard at it and she really did plot and plan and be incredibly self-critical. Many members of her cabinet who were not of her ideological persuasion began to develop a sneaking regard for this woman."

Makeover

As leader of the opposition, Mrs Thatcher famously had voice training at the National Theatre to improve her diction to make it sound more authoritative.

Her wardrobe also got a makeover - with less "fussy, patterned" outfits, as befitting someone who aspired to the highest office in the land.

Margaret Thatcher's diction and wardrobe both evolved on her way to Downing Street

"She would not change her opinions, which remained pretty solidly conventionally Conservative," says Shirley Williams, who was shadow health secretary at the time and observed her opponent's "amazing" rise in an otherwise male-dominated party.

"But she certainly was absolutely ready to change aspects of her appearance or her clothing or whatever that would actually make her look more like a prime-minister-in-waiting.

"She was very ambitious. She actually feeds on obstacles and feeds on problems and grows on them."

She might, as Mr Clarke puts it, not have had any "light banter conversation" other than politics but Mrs Thatcher was deadly serious about where she was heading.

"The person who was elected leader of the opposition was a startling accident," he says. "The woman who became elected prime minister was ready to be prime minister."

Thatcher: A Very British Revolution begins on BBC Two at 21.00 BST on Monday 20 May