Vince Cable: As Lib Dem leader stands down, what is his legacy?

- Published

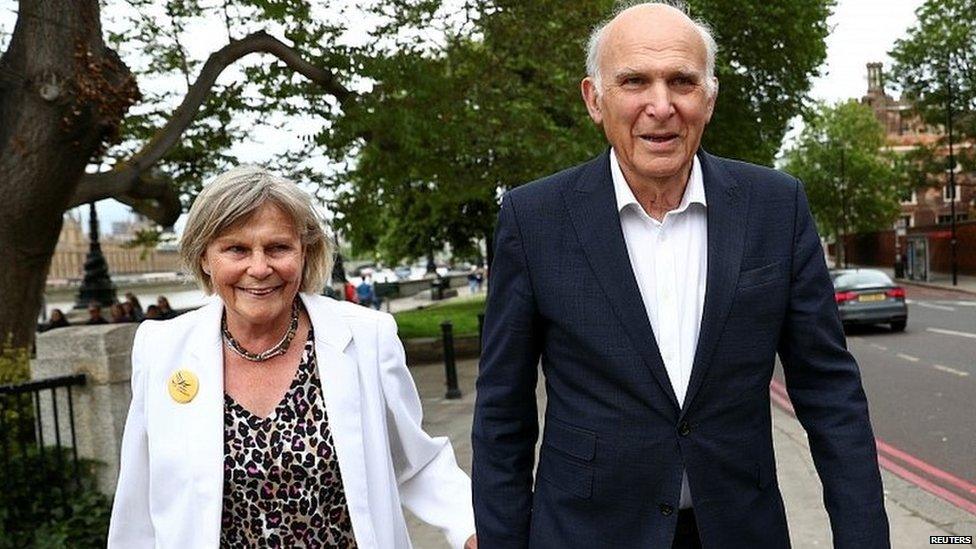

The 76-year old is stepping down with his party on the rise

Expectations were low when Sir Vince Cable became Lib Dem leader in July 2017.

The party was still in the political wilderness after its hammering in the 2015 general election.

It hadn't made the progress it had hoped for in 2017's snap poll, and Tim Farron had quit suddenly as leader amid uncomfortable questions over his views on faith and homosexuality.

MPs weren't exactly queuing up to replace Mr Farron - Sir Vince was elected unopposed. He inherited a party that seemed to be going nowhere, fast.

Almost two years later, the picture couldn't be more different. His successor - who will be announced on Monday - will take over a party with a real spring in its step and genuine optimism about the future.

So how did the turnaround happen and how much credit should the outgoing leader get for it?

Riding an anti-Brexit wave

A consistent and populist anti-Brexit stance has reaped its rewards

There is plenty of evidence to suggest the improvement in the party's fortunes is inextricably linked to this year's Brexit deadlock and the political polarisation that has followed.

Even as recently as last autumn, the party was struggling to get its anti-Brexit voice heard as it appeared the UK was inexorably on course to leave the EU on 29 March.

While Sir Vince made his most passionate pro-Remain speech to date at the September Lib Dem conference, coverage of it was somewhat overshadowed by his odd description of the 2016 Brexit vote as an "erotic spasm" or, as he actually delivered it, "exotic spresm".

The party had been an early advocate of another referendum on the terms of the UK's withdrawal - or as senior figures liked to call it, the "first referendum on the facts".

Sir Vince's own position on the issue certainly evolved.

In 2016, he said it was "disrespectful" to voters and "politically counter-productive" to call for a fresh vote. That had morphed into support for one by the time he became leader - although he focused on calling for a vote, external once the terms of a Brexit deal were clear, or if no deal appeared to be on the cards

By the summer of 2018, there were signs that the party's shift in position was beginning to bear electoral fruit.

In the Lewisham by-election that June, the party's vote rose by 20% and its candidate, Lucy Salek, made impressive inroads into Labour's majority in an area that had voted heavily to remain in 2016.

With Labour's own contortions on Brexit and a so-called "People's Vote" becoming increasingly painful for many of its supporters, this was a harbinger of things to come.

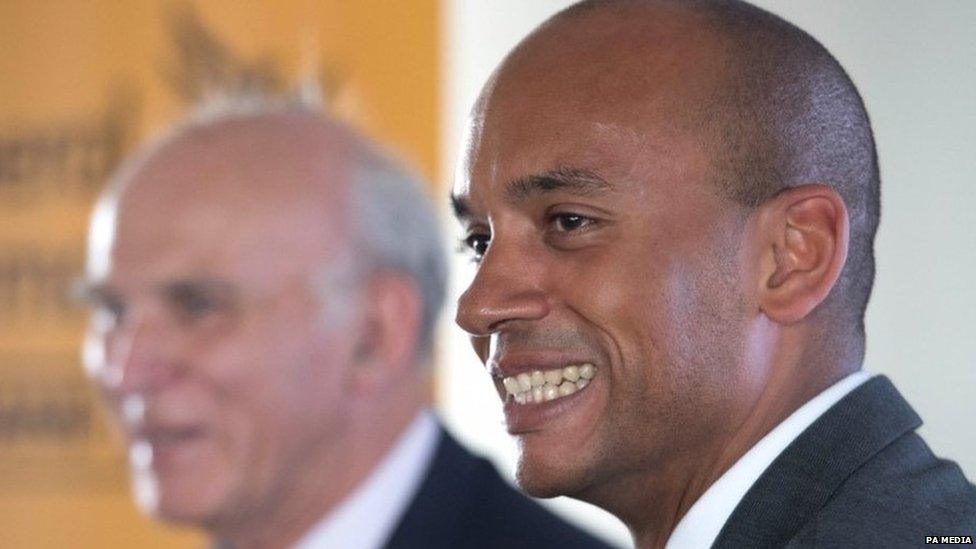

Confronting Change UK challenge

Getting Chuka Umunna on board was a real coup for the party

The first few months of 2019 brought new opportunities but also threats for the Lib Dems.

The scale of Conservative opposition to Theresa May's withdrawal agreement, rejected for the first time in January by 230 votes, magnified the prospects of a no-deal exit - a fear the Lib Dems were able to play on.

But, at the same time, the emergence of a new anti-Brexit party coveting the same political ground occupied by the Lib Dems provided an unexpected challenge.

Change UK - The Independent Group launched with great fanfare, but quickly flopped at the ballot box.

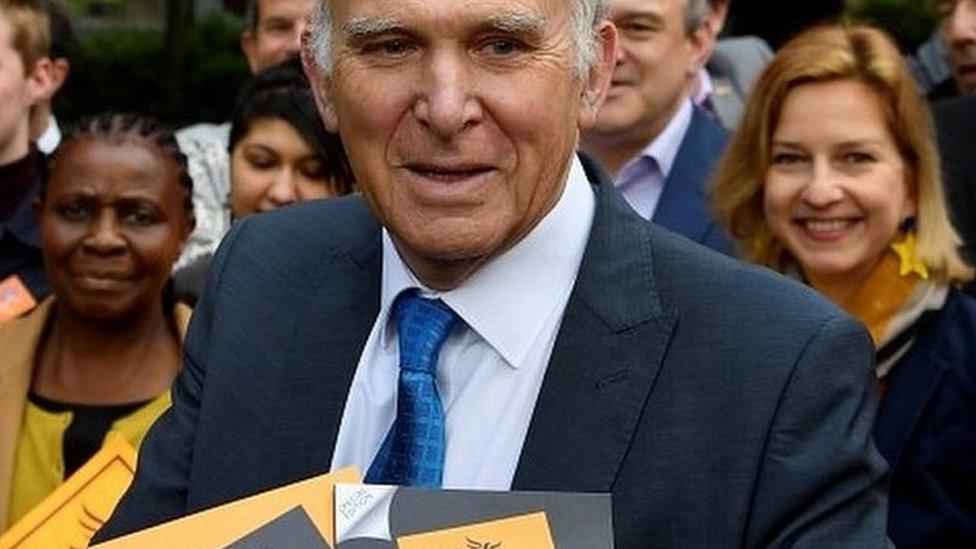

In contrast, the Lib Dems enjoyed their best-ever performance in the European elections - getting 20% of the vote - on the top of an earlier resurgence in English council polls.

This showed two things. Firstly, that the party's organisational machine, strengthened by the addition of thousands of new members since the 2016 vote, was in good working order.

And more importantly, the party's brand - contrary to what some Change UK MPs claimed - had not been irreparably tarnished by the legacy of its coalition with the Conservatives.

In fact, its now full-throated support for another EU referendum - it adopted the "Bollocks to Brexit" slogan for the campaign - struck a chord at a time when Labour was continuing to prevaricate and the Conservatives were in internal turmoil.

The fact that Chuka Umunna, perhaps the biggest name in the Change UK stable, joined the Lib Dems soon afterwards vindicated Sir Vince's handling of the whole episode.

A leadership of two halves

Like Tim Farron before him, Vince Cable often struggled to get his voice heard in Parliament

The irony is that Sir Vince is standing down at a moment when his position has never been more secure.

This was not always the case. Internal critics, and even some supporters, thought the first year of his leadership was underwhelming.

While he was a calm, reassuring presence after Tim Farron's turbulent last few months, there was a seeming absence of new policies and his big idea of turning the party into a broad-based liberal movement was seen as a long-term ambition at best.

His media profile was relatively under-powered - certainly compared with his famed ubiquity during the 2008 financial crisis.

Sir Vince Cable: "I think before this summer is out, we will get more defections."

While there was no talk of a challenge, there was little surprise when the 76-year old - who assumed his career in frontline politics was over when he lost his seat in 2015 - signalled in September 2018 that he would leave once Brexit was "resolved or stopped".

On that basis, Sir Vince - who was seen by some as a caretaker leader when he accepted the job - would have a case for staying on, particularly with the wind in his sails.

It would surely be tempting to try and capitalise on the momentum that his united party have - with a winnable by-election in Brecon and Radnorshire around the corner.

But few politicians these days get to choose the moment of their departures let alone to go out on a high - ask Theresa May.

Political challenges for successor

Have the Lib Dems finally banished the memories of the coalition years?

Sir Vince has only been in the job for two years, but that's longer than two of his three immediate predecessors - Mr Farron and Sir Menzies Campbell.

Mr Farron says his legacy is to have saved his party from possible extinction after its trauma in 2015.

Sir Vince has undeniably built on that achievement and put the party back on the electoral map.

But what he has not done, due to lack of time or perhaps inclination, is address some of the longer-term challenges facing the party.

Ed Davey, one of the two candidates hoping to succeed him, has said voters do not really know what the party stands for, aside from its opposition to Brexit. He thinks the Lib Dems have missed an opportunity to become the party of the environment and education.

This shortcoming and, some of the other philosophical contradictions resulting from the party's years in coalition with the Conservatives, remain unresolved.