Dominic Cummings: How does he now earn a living?

- Published

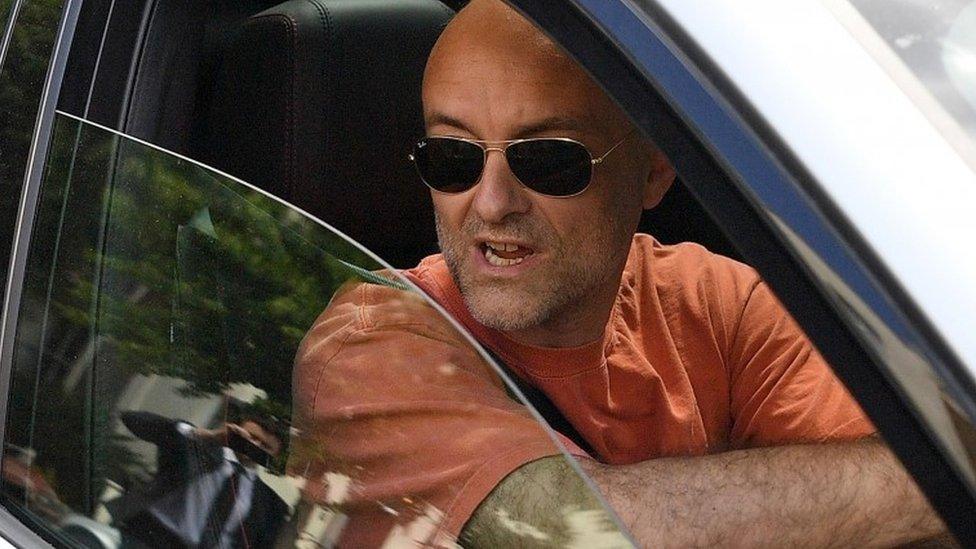

Pictures of Mr Cummings leaving No 10 dominated newspaper front pages

Dominic Cummings was never going to go quietly after being forced out of Downing Street at the end of last year.

But the number, and seriousness, of his claims about what went on at the heart of government, as ministers battled to get on top of the coronavirus crisis, are unprecedented in modern times.

Rarely has a former adviser made so many potentially damaging revelations about a sitting prime minister.

His critics say Mr Cummings is motivated by revenge against Boris Johnson, and will not rest until the PM has been removed from No 10.

Mr Cummings insists he is driven by a desire to make what he views as a broken and chaotic government machine work better in future.

He left his Downing Street role following an internal power struggle, amid claims the PM's then-fiancee had blocked the promotion of one of his allies, Lee Cain, after months of internal warfare.

In his final year at Downing Street, Mr Cummings had a £40,000 pay rise, taking his salary to between £140,000 and £144,999.

Tech consultancy

There was speculation that the 49-year-old would seek a post-politics career as the first head of Aria, the UK's new "high risk" science agency, which had been one of his pet projects.

But he appears to have a different career path in mind.

In February, he started a technology consultancy firm, Siwah Ltd. He is the sole director of the firm, according to Companies House, external, and it is registered at an address in his native Durham, in north-east England. This would appear to be a successor to Dynamic Maps, his previous tech consultancy.

But in recent months, most of his time appears to have been taken up with spilling the beans on his time in government.

The BBC did not pay Mr Cummings for his exclusive interview with political editor Laura Kuenssberg.

And he has not yet taken the time-honoured route of selling his story to a newspaper, or signing a book deal.

But he has found a way of generating income through online platform Substack, where he has launched a newsletter.

Angry watchdog

He plans to give out information on the coronavirus pandemic and his time in Downing Street for free, but "more recondite stuff on the media, Westminster, 'inside No 10', how did we get Brexit done in 2019, the 2019 election etc" will only be available to subscribers who pay £10 a month.

He is also offering his marketing and election campaigning expertise, for fees that "slide from zero to lots depending on who you are / your project".

This new venture has incurred the wrath of Whitehall watchdog Lord Pickles, who chairs the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (Acoba), which vets jobs taken by former ministers and top officials.

In a letter to Cabinet Office Minister Micheal Gove, he says Mr Cummings has sought advice on working as a consultant.

But he adds: "It appears that Mr Cummings is offering various services for payment via a blog hosted on Substack, the blog for which he is also receiving subscription payments.

"Mr Cummings has failed to seek the committee's advice on this commercial undertaking, nor has the committee received the courtesy of a reply to our letter requesting an explanation.

"Failure to seek and await advice before taking up work is a breach of the government's rules."

There are few repercussions for failing to consult Acoba, however.

Barnard Castle trip

Little was heard from Mr Cummings for several months after his departure from Downing Street - but that all changed in April.

After being named in media reports as the source of government leaks, he launched a scathing attack on Mr Johnson via a 1,000-word blog post in April.

As well as denying he was behind the leaks, he went on to make a series of accusations against the PM and questioned his "competence and integrity".

The following month, Mr Cummings expanded on his criticisms at a seven-hour select committee appearance, declaring Boris Johnson "unfit for the job", and claiming he had ignored scientific advice and wrongly delayed lockdowns.

He also turned his fire on then-health secretary Matt Hancock, who he said should have been fired for lying.

This sparked a bitter war of words with Mr Hancock, who flatly denied all of Mr Cummings's allegations.

It thrust Mr Cummings back into the spotlight for the first time since his now infamous visit to County Durham, four days after the start of the first national lockdown, in March last year.

Cummings challenged over lockdown trip to Durham

While staying with his family at his father's farm, he made a 30-mile road journey to Barnard Castle, which he later said had been to test his eyesight before the 260-mile drive back to London.

This revelation - at a specially-convened press conference in the Downing Street garden - made Mr Cummings a household name and led to furious allegations of double standards at a time when the government had banned all but essential long-distance travel.

In an interview with BBC Political Editor Laura Kuenssberg, Mr Cummings said that, during the Barnard Castle trip, he had been trying to work out "Do I feel OK driving?"

He also said he had decided to move his family to County Durham before his wife fell ill with suspected Covid because of security concerns over his home in London.

Asked why he had given a story that was "not the 100% truth" when he held a special press conference in the Downing Street rose garden on 25 May, Mr Cummings admitted that "the way we handled the whole thing was wrong".

Cummings says he drove to Barnard Castle to test vision

Boris Johnson stood by his adviser throughout the Barnard Castle episode - to the consternation of some of his supporters, who feared it was undermining his attempts to hold the country together during a national crisis.

Some said the episode burned through the political capital the prime minister had generated months earlier during the 2019 general election.

Boris Johnson defends his senior adviser Dominic Cummings in May 2020

But it is hard to overstate how important Mr Cummings was to the Johnson project.

Ruthless strategist

The two are very different characters - Mr Johnson likes to be popular, Mr Cummings appears indifferent to such concerns - but they formed a strong bond in the white heat of the 2016 Vote Leave campaign to get Britain out of the EU, which Mr Cummings led as campaign director.

The combination of Mr Johnson, the flamboyant household-name frontman, with Mr Cummings, the ruthless, data-driven strategist, with a flair for an eye-catching slogan, proved to be unbeatable.

Mr Cummings was credited with formulating the "take back control" slogan that appears to have struck a chord with so many referendum voters, changing the course of British history.

Yet some were surprised when Mr Cummings was brought into the heart of government as Mr Johnson's chief adviser, given his past record of rubbing senior Tory politicians up the wrong way.

It proved to be a shrewd move. It was Mr Cummings who devised the high-risk strategy of pushing for the 2019 election to be fought on a "Get Brexit Done" ticket, focusing on winning seats in Labour heartlands, something no previous Tory leader had managed to do in decades.

'Levelling-up'

Many of the policy ideas that have shaped the Johnson government's agenda have his fingerprints all over them.

"Levelling up" - moving power and money out of London and the South East of England - is a Cummings project, as are plans to shake-up the civil service, take on the judiciary and reform the planning system.

The team that surrounded Mr Cummings at Downing Street, some of whom are Vote Leave veterans, were fiercely loyal to him and shared a sense that they were outsiders in Whitehall, battling an entrenched "elite".

Lee Cain, the former Downing Street and Vote Leave communications chief, left No 10 just before Mr Cummings did.

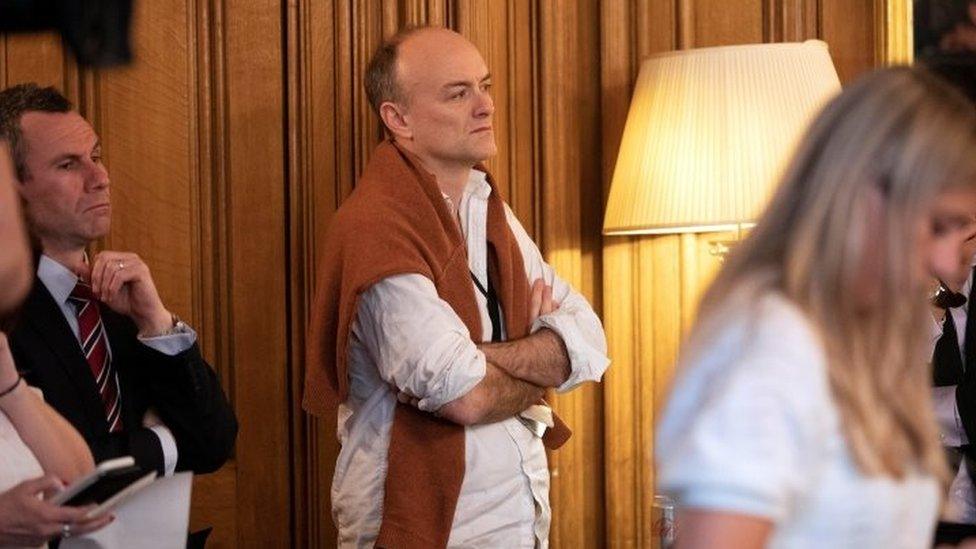

Mr Cummings watches the PM in action at a coronavirus briefing

There had been rumours of a rift between the Vote Leave veterans and other No 10 aides, who didn't like Mr Cummings's and Mr Cain's abrasive style.

There were tales of crackdowns on special advisers suspected of leaking to the media and angry, dismissive behaviour towards Tory MPs, civil servants and even secretaries of state.

None of this will have come as much of a surprise to veteran Cummings watchers.

'Weirdos and misfits'

Mr Cummings has been in and around the upper reaches of government and the Conservative Party for nearly two decades, and has made a career out of defying conventional wisdom and challenging the established order.

But he has never been a member of the Conservative Party, or any party, and appears to have little time for most MPs.

A longstanding Eurosceptic who cut his campaigning teeth as a director of the anti-euro Business for Sterling group, Mr Cummings's other passion is changing the way government operates.

He grabbed headlines when he posted an advert on his personal blog for "weirdos and misfits with odd skills" to work in government, arguing that the civil service lacked "deep expertise" in many policy areas.

The Vote Leave bus was one of its most notable campaign tactics

Mr Cummings is a native of Durham, in the North East of England. His father, Robert, was an oil rig engineer and his mother, Morag, a teacher and behavioural specialist.

He went to a state primary school and was then privately educated at Durham School. He graduated from Oxford University with a first-class degree in modern history and spent some time in Russia, where he was involved with an ill-fated attempt to launch an airline, among other projects.

He is married to Spectator journalist Mary Wakefield, the daughter of aristocrat Sir Humphry Wakefield, whose family seat is Chillingam Castle, external, in Northumberland.

After a stint as campaign director for Business for Sterling, Mr Cummings spent eight months as chief strategy adviser to then Conservative leader Iain Duncan Smith, who fired him.

He played a key role in the 2004 campaign against an elected regional assembly in his native North East.

'Career psychopath'

In what turned out to be a dry run for the Brexit campaign, the North East Says No team won the referendum with a mix of eye-catching stunts - including an inflatable white elephant - and snappy slogans that tapped into the growing anti-politics mood among the public.

He is then said to have retreated to his father's farm, in County Durham, where he spent his time reading science and history books in an effort to attain a better understanding of the world.

Mr Cummings facing questions from the media outside his home

He re-emerged in 2007 as a special adviser to Michael Gove, who became education secretary in 2010 and turned out to be something of a kindred spirit.

The pair would rail against what they called "the blob" - the informal alliance of senior civil servants and teachers' unions that sought, in their opinion, to frustrate their attempts at reform.

He left of his own accord to set up a free school, having alienated a number of senior people in the education ministry and the Conservative Party.

He once described former Brexit Secretary David Davis as "thick as mince" and as "lazy as a toad" and irritated David Cameron, the then prime minister, who called him a "career psychopath".

Benedict Cumberbatch was widely praised for his portrayal of Dominic Cummings in Brexit: The Uncivil War

His appointment as head of the Vote Leave campaign - dramatised in Channel 4 drama Brexit: The Uncivil War - was seen as a risk worth taking by those putting the campaign together but he left a controversial legacy.

Vote Leave was found to have broken electoral law over spending limits by the Electoral Commission and Mr Cummings was held in contempt of Parliament for failing to respond to a summons to appear before and give evidence to the Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee.

Like most advisers, he shunned media interviews when he was in government, and his rare appearances before MPs were characterised by animosity on both sides.

All that has changed in recent weeks, but it would be a brave person who said he had now joined the ranks of the former Westminster insiders who make their living as pundits - a class he appears to view with as much disdain as he does his former colleagues in government.

- Published24 May 2020

- Published27 September 2019

- Published27 March 2019

- Published5 January 2019