Why it’s proving hard to nail an election date

- Published

The prime minister has made his pitch.

Labour, in his view, is "frit" of an election, and another attempt to call an early poll will be attempted on Monday.

Will Labour fold under pressure of allegations of cowardice… or will it continue to refuse to give him what he wants?

There have been different views inside the Labour hierarchy but - at the time of writing - these appear close to being reconciled.

Shadow chancellor John McDonnell has been pretty transparent about the nature of the debate - whether to agree to an early election, or one that takes place slightly later.

And it would appear that Jeremy Corbyn is being persuaded to wait.

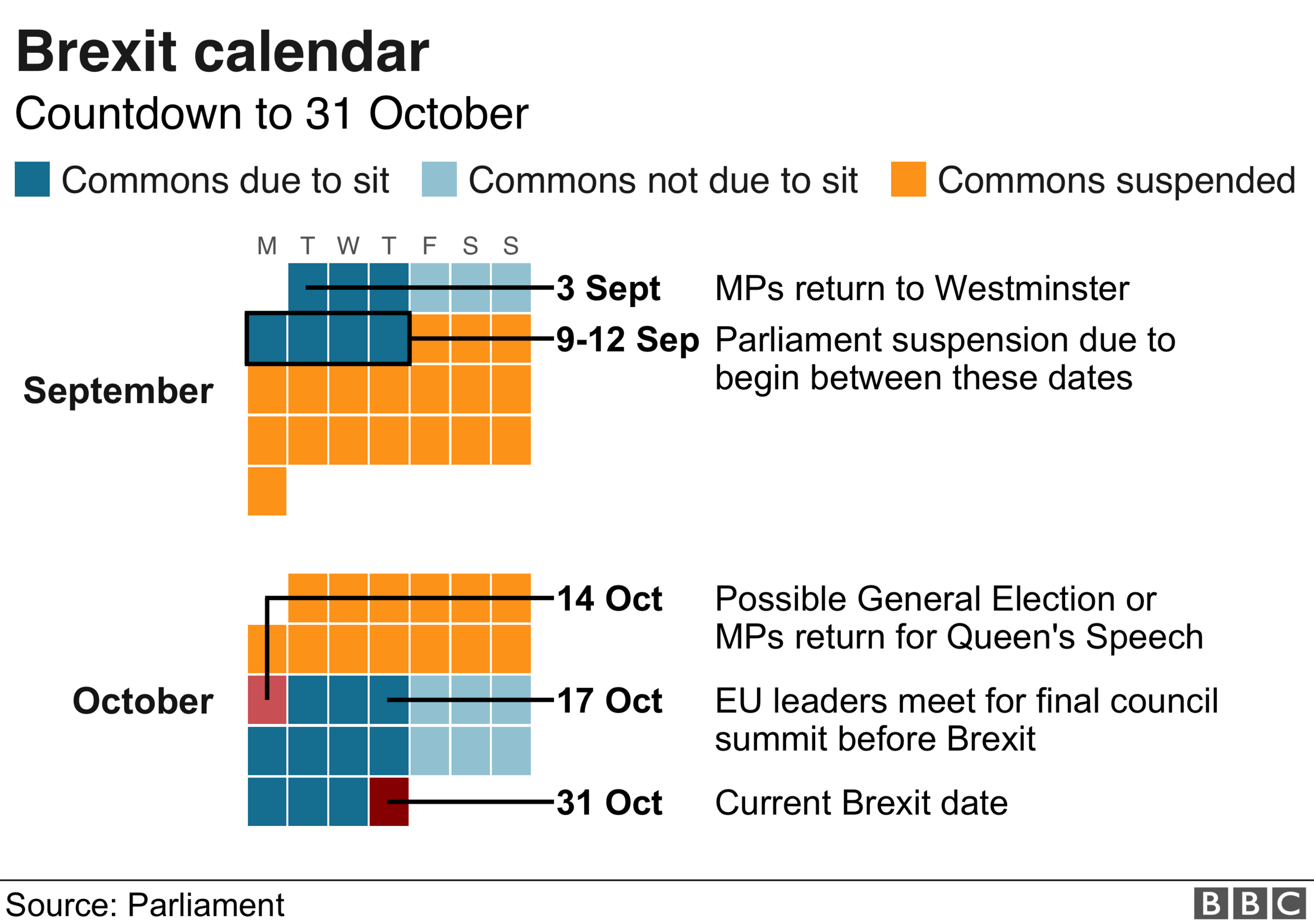

"Later" would be after 19 October - when Boris Johnson would be required by Parliament to seek a Brexit delay following the passage of Hilary Benn's anti-no-deal bill.

Mr Corbyn has said when that bill - to delay Brexit - gets royal assent, Labour will consider agreeing to an election at that stage.

Others, including shadow Brexit secretary Sir Keir Starmer, have indicated that Labour should wait until the bill isn't just passed, but implemented.

Royal assent is expected to happen on Monday, and the government has made clear it will ask Parliament for an election again straight afterwards.

It has said this would be under the Fixed Term Parliaments Act, requiring a two-thirds Commons majority for it to be approved.

So Labour's position will be crucial to when an election is held.

Shadow cabinet disagreements

Mr Corbyn and key advisers had believed it was better to go early.

But other influential figures in the shadow cabinet disagreed - including Mr McDonnell and deputy leader Tom Watson.

They argued it was better to force Mr Johnson either to ask for a Brexit extension - breaking a key promise - or refuse to do so, opening him up to a motion of no confidence and giving the opposition the chance to form a temporary administration.

The pivotal figure of Len McCluskey - leader of Unite, Labour's largest affiliated trade union - was something of a floating voter between the two positions.

But his instinct was to "make Boris wait - and squirm".

And it appears he is now moving closer to Mr McDonnell's view.

This in turn is persuading Mr Corbyn to block Boris Johnson's election request.

But Mr McCluskey and other senior Labour figures have been concerned that the SNP would leave Labour high and dry by agreeing to an election on Monday, and making Mr Corbyn look scared.

Labour would, to an extent, be inoculated from charges of dither and delay if the whole opposition remains united.

Boris Johnson has criticised Labour for not backing his call for an election

And it now looks like the "rebel alliance" is holding, following cross-party talks at which the SNP's Westminster leader and Mr Corbyn were present.

There may have been tensions between the SNP in Edinburgh - the party leader Nicola Sturgeon has said she wants to "bring on" an early election - and the SNP at Westminster.

Senior SNP figures in London are alive to the possibility that if Mr Johnson is elected in a snap poll and goes for no-deal, the party would be open to the charge of enabling it.

And if it turned out, post-election, that Mr Johnson had no overall majority, good relations with Labour and the Lib Dems at Westminster might bring a second independence referendum closer.

So the opposition alliance is holding.

I am told they are together seeking to find a "mechanism" which enables an election but does not enable no-deal.

So, with the help of Commons Speaker John Bercow, could they change what was assumed to be the unamendable Fixed Term Parliaments Act to insert an election date - but one which comes after the date when Mr Johnson is required to seek a Brexit delay?

Whitehall sources have said if the Speaker is "flexible" and allows amendments, the government would be happy to specify 15 October - before an EU summit beginning two days later, and before an extension is required.

This would allay fears that the prime minister might subsequently change the election date to beyond 31 October so that Brexit happens by default.

But these sources are adamant he won't agree to a different date set by the opposition.

So what happens if there is no election by the time a Brexit delay is required?

One idea being floated is that Labour successfully calls a motion of no confidence in Boris Johnson because he has defied Parliament.

Mr Corbyn would form a temporary administration and extend the deadline.

But Tory sources say the Conservatives could then call for a motion of no confidence in Mr Corbyn.

Tory rebels would return to the fold, and Mr Johnson would win the vote.

He would fail then to form a government within the specified two-week timescale, after which the law demands an election be called.

He would then attack Mr Corbyn for the Brexit delay.

There are many other scenarios - including Mr Johnson vetoing his own government's request for a Brexit extension at a Brussels summit (not clear if he could), or getting another European leader to do so, because he makes clear he doesn't want it.

Far-fetched, perhaps.

But these days, extraordinary is the new normal.

- Published5 September 2019

- Published13 July 2020