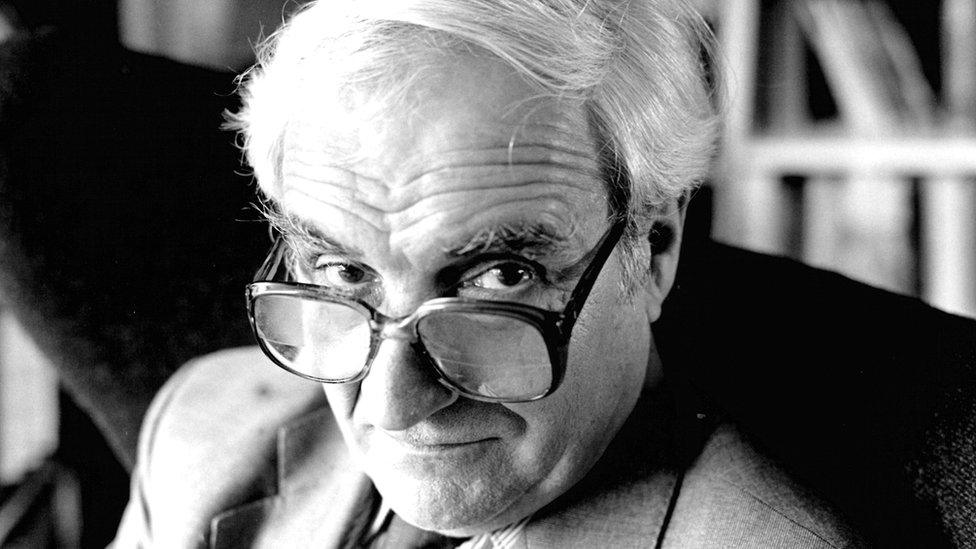

Sir David Butler, pioneering election analyst, dies aged 98

- Published

Sir David Butler, a trailblazing former BBC election analyst who pioneered exit polls and the concept of vote swing, has died at the age of 98.

The polling maestro was hailed as "the father of election science" by his friend and biographer, Michael Crick.

Sir David was a staple of the BBC's election night coverage for decades, analysing results on air from 1950 to 1979.

He co-invented the swingometer, a graphics device used to show the shift of votes from one party to another.

He dubbed his craft "psephology", based on the Greek word "psephos" for pebble, which the ancient Greeks used to vote in elections.

Tributes have been paid by his admirers, including pollster Anthony Wells, who said being able to talk to Sir David was like "a physicist getting to meet Newton".

BBC News and Current Affairs chief executive Deborah Turness said Sir David had "played a hugely important role in the development and modernising of the BBC's election coverage", adding that generations of audiences "looked to him for clear analysis and commentary".

Born out of boredom

Advances in human understanding are often the product of boredom.

Archimedes was lazing in the bath when inspiration struck and Newton's apple - quite literally - fell upon a daydreaming head.

Sir David's first love was cricket, especially working out the batting and bowling averages. But when the County Championship was suspended during World War Two, he found himself twiddling his thumbs.

To pass the time, he tried applying the same mathematical rigour to his other passion: election results.

Today, every opinion poll and vote is picked over and analysed but until Butler idly began turning raw election results into percentages, it had not occurred to anyone that it might be worthwhile.

A new academic discipline was born out of boredom, its 21-year-old father still barely old enough to vote.

Butler called his brainchild "psephology" - a play on the Greek word for pebble. It was intended as a joke as pebbles were the means by which the ancients cast their ballots.

"You must meet my brilliant young nephew," gushed his aunt in triumph. "He's devised a method of forecasting elections based on bowling averages."

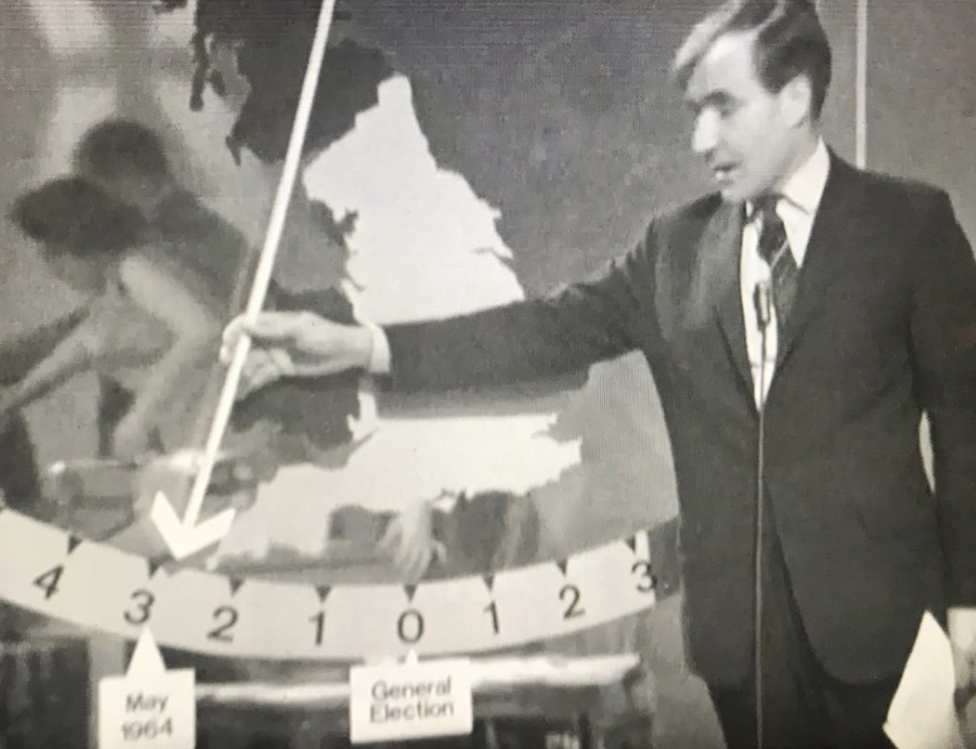

David Butler demonstrates the swingometer on BBC Election Night

Academic dynasty

David Henry Edgeworth Butler was born on 17 October 1924. Inevitably, he emerged just days before Britain went to the polls in an election that saw Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government thrown out after nine months in office.

He became part of one of Britain's most academically distinguished dynasties, the Butler family tree boasting numerous Oxford dons and respected writers.

His parents were connected to the legendary Bloomsbury set of intellectuals, and the future Conservative deputy prime minister "Rab" Butler was a cousin. For young David, politics and academia were the childhood air he breathed.

"I remember him talking about Abyssinia, and the Italian invasion," recalled his prep school friend, broadcaster Nicholas Parsons. "He had great knowledge for a youngster."

His teachers were less convinced. "David has many very nice traits," wrote one rather oddly, "but he is a bit whimsical, puerile, and I think probably suffers from having elder sisters."

In 1942, he arrived at New College, Oxford. He joined the Conservative, Labour and Liberal clubs, his determination to experience student political life to the full overcoming any personal ideology.

On the first day, his new tutorial partner bounded over. David Butler often had little patience for Tony Benn's left-wing politics, but the two men became lifelong friends.

David Butler became firm friends with Tony Benn at Oxford - although neither thought much of the other's politics

After two terms, Butler joined the Staffordshire Yeomanry. He did officer training at Sandhurst, and found himself - still only 19 - leading a daring crossing of the Rhine in a fleet of amphibious tanks.

"Mercifully, I didn't manage to kill any of my people," he told his biographer, the journalist Michael Crick.

Hurry up, young man…

Back in Oxford, Butler began developing the field of psephology. He worked out how results could be expressed as percentages and how they "swung" between elections.

In 1945, he helped put together the first systematic account of an election campaign itself - documenting the swirling political currents that propelled Attlee to victory.

He was quick to see how George Gallup's new American opinion polls might be imported - and used to predict the outcome of future elections.

And he developed a theory: that the number of seats a party won in a general election was proportional to the cube of the votes it received. It wasn't exactly a page turner, but he got the Economist to publish it.

Out of the blue, he was summoned by Churchill. Butler hastened to Chartwell - where the great man emerged, glowing pink from his bath.

Sir Winston Churchill summoned David Butler to explain his theories

Sir Winston had read the article - but swiftly tired of discussing its complexities. Instead, he delivered a long, private masterclass on the art of wartime leadership.

"You're 25? You'd better hurry up, young man," he told an awed Butler. "Napoleon was 26 when he crossed the bridge at Lodi."

The swingometer

In 1950, the BBC had a radical idea. The Corporation did not - and assumed it never would - dive into the controversial waters of an election campaign itself. But what about reporting the results?

On camera, Butler reeled off statistic after statistic comparing each result with the previous election and weaving in details about candidates. His only thinking time was the 30 seconds it took for the paint to dry on the captions.

He bombarded BBC producers with ideas for future Election Nights. One letter included a sketch of a "pendulum device": the swingometer.

It was deceptively simple, which is just how TV likes it. 1950s Britain was pretty homogenous so if one constituency "swung" towards a particular party, then all the others would probably follow.

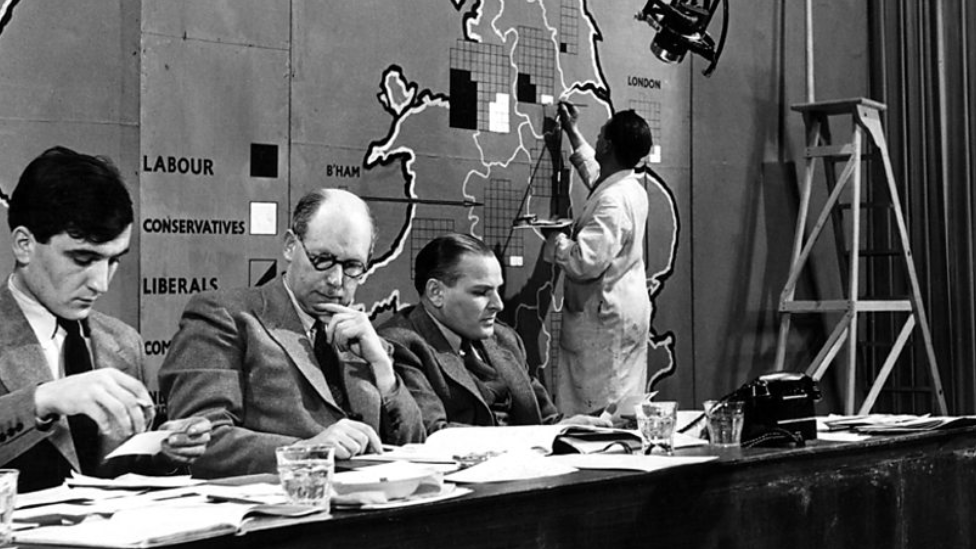

David Butler crunches the numbers on the BBC's Election programme in 1959

The swingometer could therefore show - after only a few results - what the final outcome would be. At first, Butler drove it himself - but later handed the keys to Bob McKenzie, Peter Snow and Jeremy Vine.

Working on the 1961 Election Night programme, he met a young producer - Marilyn Evans. Just weeks later, he went down on bended knee at an Oxford ball.

"Don't be so bloody silly, David," she said. "It is much, much too soon." But eventually, she was persuaded and - to his great pride - Marilyn Butler's academic career went on to eclipse his own.

She became a distinguished professor at Cambridge and head of an Oxford college but David's lack of interest in big ideas and abstract concepts held him back professionally.

"He was always a man for facts, figures and statistics," observed Michael Crick. "But he was uncomfortable with pure philosophy."

What worked so well on television did not always impress university colleagues and Butler never became an Oxford professor.

'Insolent Pom'

Between elections, he spent time in America - serving as personal assistant to the British ambassador - and took his swingometer to Australia.

Some resented a Brit commenting on politics down under. "Insolent Pom insults PM" was one headline, when he called the prime minister, Harold Holt, a "disappointment".

David Butler caused controversy when he described Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt as disappointing - days later, Holt disappeared while swimming

Days later, Holt vanished. He had been seen swimming in rough seas, but some accused Butler of driving the prime minister to suicide.

It was a pre-internet conspiracy theory, delivered by telegrams rather than Twitter. Even in the age of deference, Butler's criticism had been fairly mild - but the backlash was uncomfortable nonetheless.

The exit poll

The 1970 election saw another innovation - the BBC's first exit poll. David Butler identified Gravesend in Kent as the most representative constituency in Britain - and a team of pollsters was dispatched.

Against all expectations, Gravesend forecast a big swing to the Conservatives. Harold Wilson ventured the opinion that it could still be "very close" but Butler's rejoinder was withering.

"I hate to disagree with a fellow member of the Royal Statistical Society, especially as he's still prime minister," he said, "but I don't think there can be any doubt about the outcome." Harold Wilson lost both the argument and the election.

In 1979, Butler did his last stint as BBC TV's election night wonk-in-chief. He became BBC Radio 4's resident numbers-man well into the 1990s - and was awarded a CBE.

The BBC's Election Night team in 1979: David Butler, Angela Rippon, David Dimbleby and Bob McKenzie

There was sadness when Marilyn suffered her slow decline to dementia, and horrible shock when one of their talented sons - Gareth - died suddenly of a heart attack. But David continued to chair seminars at his beloved Nuffield College, Oxford, into his 90s.

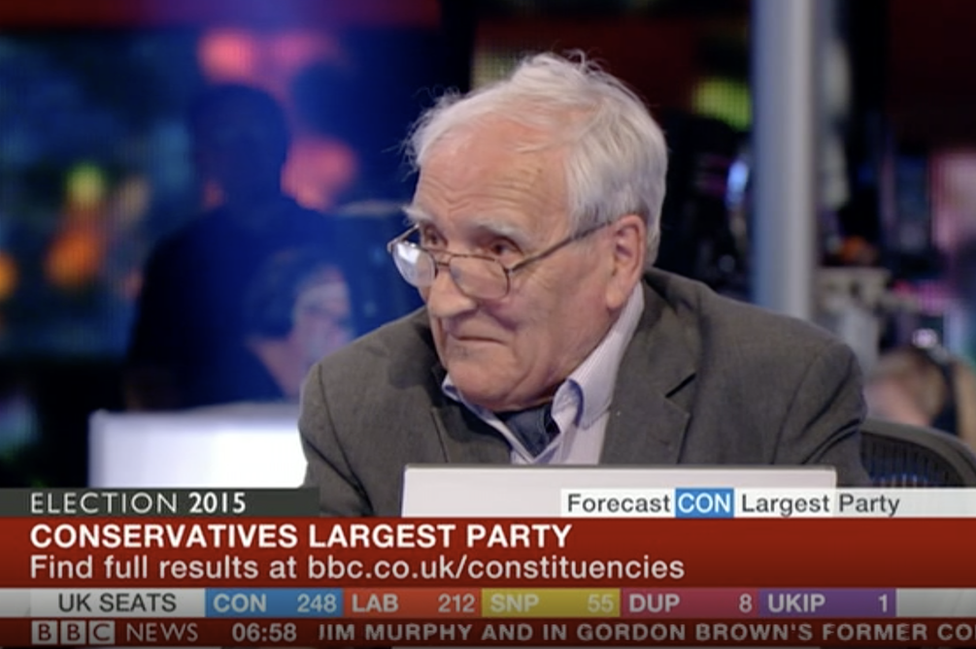

Election night return

In 2015, the BBC's election night team was asked if the grand old man could come and watch from behind the scenes. They arranged for the results to be printed out as he didn't like reading them on computers.

Just before 07:00, the programme was looking for guests still awake. The perkiest - by far - turned out to be the 90-year-old election guru so they did the obvious thing and popped him on set.

He wasn't sure about the modern graphics. It was better, he suggested, when the swingometer was made out of cardboard.

Sir David Butler appeared on the BBC Election Night programme in 2015

But two year later, he embraced that most modern of political tools and signed up to Twitter to commentate on the 2017 election.

In a month-long stint as a tweeter, he offered his musings on past campaigns and even pub quiz-style questions on politics.

And come election night itself, he used the platform to offer his new online followers the insight he had honed over years in television studios.

"Learning to tweet at 92 has been fun," he remarked. "It's wonderful to rediscover one is never too old to learn."

"I do not understand what goes on with social media," he later told an interviewer. "It is a more unpredictable world, without any doubt."

But the important thing is that Butler's brainchild is still recognised and tells the story.

"You invented that swingy thing," the Queen is said to have remarked, when giving him his knighthood.

"More or less," replied Sir David. "And it still works, doesn't it?"

- Published5 November 2018