Mavericks to mainstream: The long campaign for Brexit

- Published

It used to be a fringe obsession ignored by the political mainstream.

So how did Euroscepticism conquer Britain?

The word "Eurosceptic" was not coined until the 1980s, to describe a rebellious band of Tory MPs, but hostility to closer European integration dates back decades.

Britain voted overwhelmingly to remain in the European Economic Community in 1975, but never joined the currency or the passport-free area, and a substantial body of public opinion had always believed the country was better off out.

They rarely had a voice at Westminster. The campaign to leave the European Union - via another referendum - took root outside of Parliament. It was pursued by mavericks, political outcasts and a fair few eccentrics.

It was a long, and often thankless, battle - and it began before Britain had even joined.

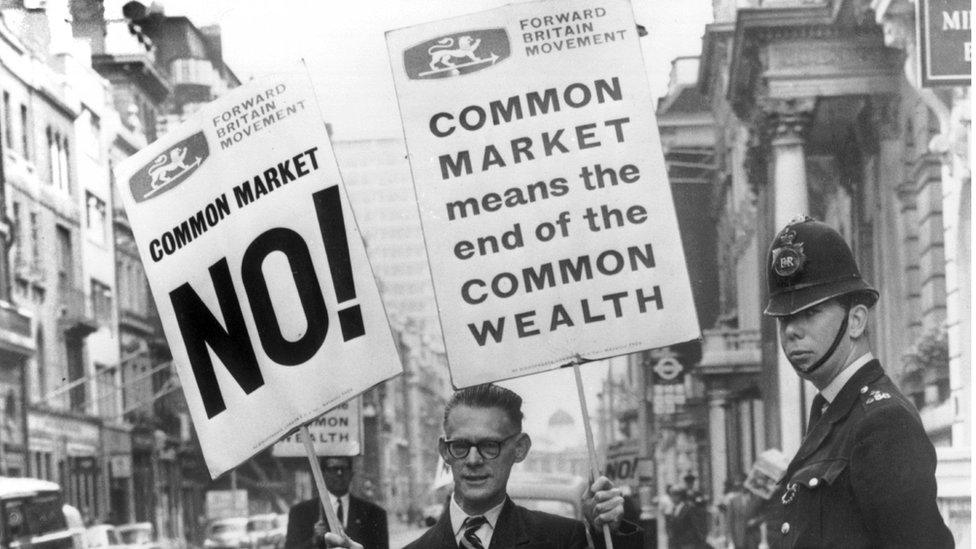

1961 - The birth of Euroscepticism

Many viewed EEC membership as a betrayal of the Commonwealth

With World War II fresh in the memory, and the Empire rapidly disintegrating, Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan decided Britain's future lay in Europe.

His, in the end unsuccessful, application to join the six nation European Economic Community enraged many in his party, who saw it as a betrayal of the Commonwealth nations, which were Britain's biggest trading partners at the time.

Many in Labour viewed the EEC as a business-led Tory con trick. Both sides fretted about the loss of independence and status it would seem to entail.

Most opponents of membership tended to be on the far left and right fringes, but there were big, mainstream voices in both the Labour and Tory parties that were also firmly against it.

"I'm not very keen on the Common Market. After all, we beat Germany and we beat Italy and we saved France and Belgium and Holland. I never see why we should go crawling to them," said former Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee.

The first substantial campaign against British membership - The Anti-Common Market League - was formed in June 1961, by a bunch of disgruntled Conservatives.

It had broadened out into a cross-party effort by the following September, when it staged a mass anti-Common Market rally at London's Albert Hall.

1967 - Keep Britain Out

Major Smedley sets off for Rome, to campaign against Britain's second, failed, attempt to join the EEC

Euroscepticism has always attracted colourful characters. Major Oliver Smedley was a decorated World War II veteran and pirate radio entrepreneur, who was cleared of murder in 1966 after he shot a business rival in a dispute over a transmitter.

Keep Britain Out stage a mock funeral for democracy in Whitehall

Maj Smedley, who quit the Liberal Party after being slow-handclapped at the party's conference, external, believed joining the "protectionist" EEC would lead to higher food prices and poverty.

His Keep Britain Out campaign merged with the Anti-Common Market League in the late 1960s and is still going today, as Get Britain Out.

1973 - Britain goes in

The tabloids were cheerleaders for Britain's membership of the EEC

On 1 January 1973, Britain officially joined the EEC, at the third attempt. Opinion polls suggested the nation was divided, external over Tory Prime Minister Ted Heath's decision. Eurosceptics, on the left and right, stepped up their calls for a referendum.

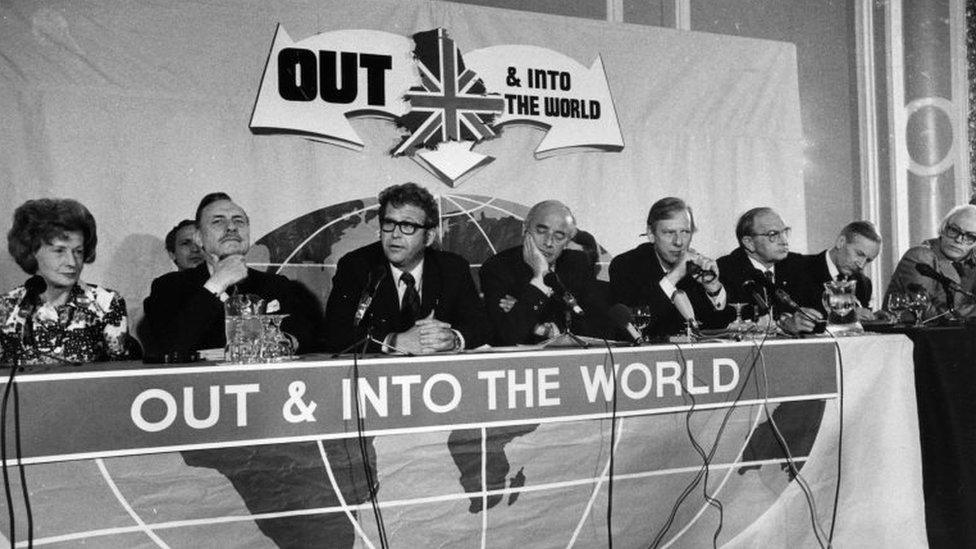

1975 - 'Out of Europe and into the world'

Enoch Powell (second left) shares a stage with future Labour leader Michael Foot (far right)

There was widespread disbelief in Eurosceptic circles when voters opted by 67% to 33% to stay in the Common Market, in the UK's first nationwide referendum.

The vote had been called by Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson largely as a way to paper over the huge divisions in his party over Europe.

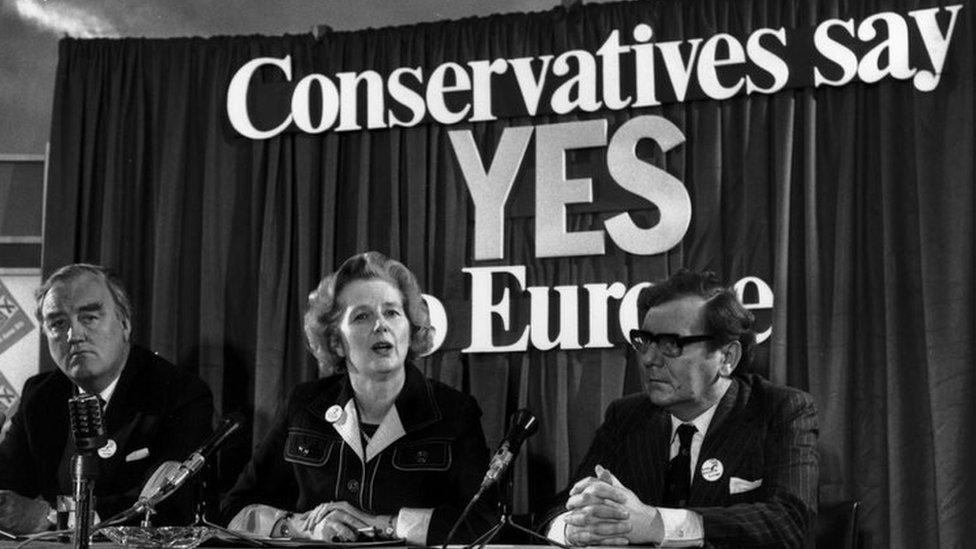

Margaret Thatcher was a leading voice in the campaign to stay in the EEC

Some polls suggested the unlikely alliance of Tony Benn, from the Labour left, and Enoch Powell, Ulster Unionist and former Tory, who emerged as the chief spokesmen for the No campaign, was a turn-off for voters.

Whatever the case, the defeat was a body blow to the Eurosceptics. Many lean years followed, with poorly attended meetings, lost election deposits and pamphlets few read, even if polls suggested Britain was turning against the EEC.

Labour campaigned to leave the EEC at the 1983 general election but went down to a heavy defeat and the Eurosceptics in its ranks were pushed to the margins.

1988 - 'A European super-state'

Margaret Thatcher warned against 'dominance from Brussels'

Margaret Thatcher's Bruges speech was the moment Euroscepticism in the UK was reborn and it arguably set Britain on the path to Brexit.

She had travelled to the Belgian city to fire a warning shot across the EEC's bows, over its ambitions to move beyond the single market to create a "social Europe", with new employment rights and regulations on business, as well as a single currency.

It all smacked of socialism by the backdoor to Mrs Thatcher, rather than the free trade area she had enthusiastically championed in 1975.

Britain's "destiny is in Europe", she stressed, but added: "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels."

It was a riposte to a speech Jacques Delors, president of the European Commission, had given to the Trades Union Congress 12 weeks earlier.

Which brings us to...

1990 - Up Yours, Delors

Jacques Delors sets out his vision of a "social Europe" at the TUC conference

In 1975, Britain's best-selling newspaper, The Sun, had told its readers: "We are all Europeans now."

In November 1990, it called on its front page for them to stick two fingers up to Jacques Delors - "Up, Yours Delors", said the headline - to "tell the French fool where to stuff his ECU" (the ECU was the forerunner of the euro).

The rest of the right-wing tabloids were now just as Eurosceptic, if not as blunt. But calling for Britain to leave was still strictly off limits in the mainstream media and politics.

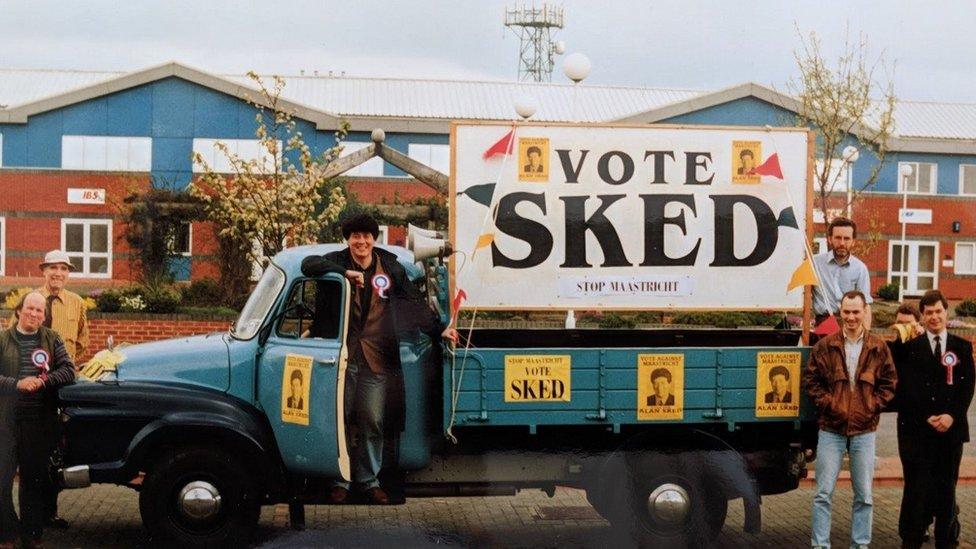

1991 - The birth of UKIP

Alan Sked came fourth in the 1993 Newbury by-election with 601 votes

It began in a dusty office at the London School of Economics. European history lecturer Alan Sked founded the Anti-Federalist League to "prevent the UK becoming a province of a united European superstate".

The tiny group, which included Nigel Farage among its early recruits, campaigned against the Maastricht Treaty, which would turn the EEC into the European Union, including a commitment to "ever closer union" and the free movement of people.

The League soon changed its name to the more voter-friendly UK Independence Party and began calling for Britain's exit from the EU. But it was largely ignored, or ridiculed, by the media, and struggled to make an impact.

Mr Sked, a former member of the Liberal Party, left in 1997, complaining that it had been taken over by right wingers and racists.

1993 - The Maastricht rebellion

Conservative MPs fought a guerrilla war against their own government's support for the Maastricht Treaty. Some of the Maastricht rebels would go on to play leading roles in the 2016 Brexit campaign (before receiving knighthoods), including Sir Iain Duncan Smith, Sir Bill Cash and Sir Bernard Jenkin.

But even the most Eurosceptic among them never spoke publicly about leaving the EU at this stage, preferring instead to talk about "reform" or, if they were in a daring mood, "fundamental reform".

1997 - Goldsmith weighs in

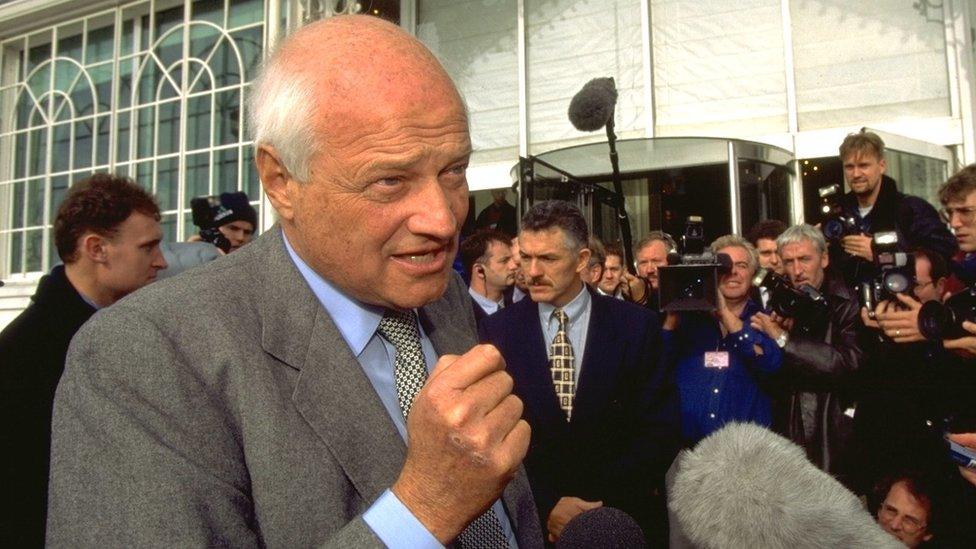

Sir James Goldsmith injected cash and energy into the Eurosceptic cause

The mercurial billionaire, and father of Conservative minister Zac, founded the Referendum Party to campaign for Britain to be given another say on Europe.

He spent more than £7m on the party's 1997 general election campaign - including a glossy promotional video mailed to five million households - for a 2.6% share of the vote.

1999 - Farage goes to Brussels

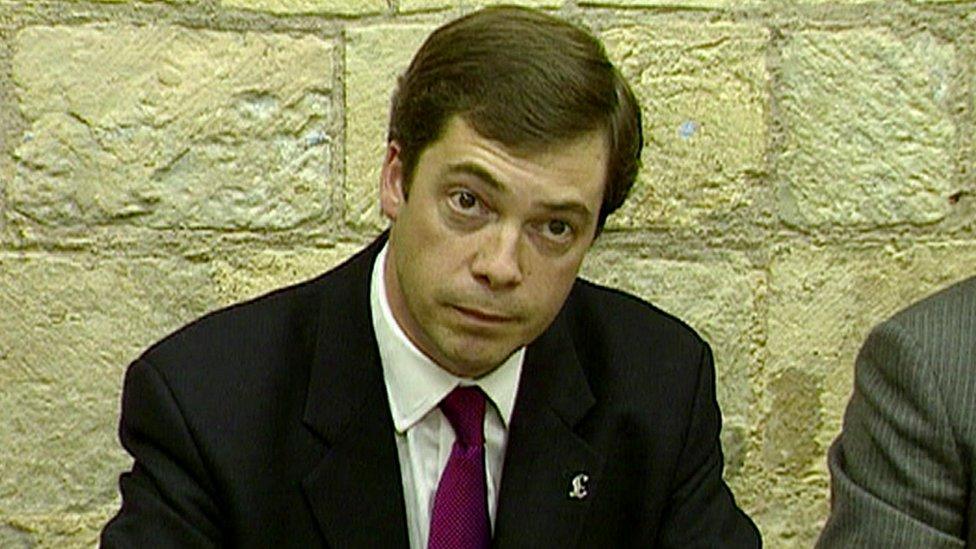

Nigel Farage was one of three UKIP candidates to make a breakthrough

In many ways, Nigel Farage owes his political career to a Belgian mathematician. In 1878, Victor D'Hondt devised the system of proportional representation adopted by the UK in 1999 for elections to the European Parliament.

UKIP and other smaller parties, like the Greens, had stood no chance under first-past-the-post. Suddenly the door to a seat in Brussels was open, and Mr Farage and two other UKIP candidates were first through it, despite receiving virtually no national media coverage for their campaign.

"Brexit wouldn't have happened without proportional representation or, ironically, the European Parliament," Mr Farage told Channel 4 News this week, external.

"It was actually getting elected to that place that gave us some kind of platform," he added, and UKIP used the "wherewithal" provided by the Brussels parliament to "build a UK political movement".

The same year saw the arrival of Dominic Cummings, future mastermind of the Vote Leave campaign, on the Eurosceptic scene, as campaign director of anti-euro pressure group Business for Sterling.

2004 - The BBC sacks a daytime TV presenter

Robert Kilroy-Silk helped to put UKIP on the political map

UKIP was still struggling for public recognition and credibility when, out of nowhere, Robert Kilroy-Silk joined it.

A household name, due to his long-running daytime talk show, Kilroy, he had been fired by the BBC over comments he'd made in a newspaper column.

Mr Kilroy-Silk's brief UKIP adventure - and the massive injection of cash that came with it, from self-made Yorkshire millionaire Paul Sykes - helped the party to the best results in its history in the 2004 European elections, gaining 2.6 million votes. UKIP - and its call for a referendum on leaving the EU - were now on the political map.

2006 - 'Fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists'

UKIP used David Cameron's insult as a rallying cry

It's possible to track the rise of UKIP in insults directed at its members by Conservative leaders, as they tried in vain to stem the flow of supporters to Nigel Farage's "People's Army".

In 2004, Michael Howard - who would go on to be a Brexit supporter - called them "extremists" and "cranks".

Two years later David Cameron refused to apologise for labelling them "fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists", handing UKIP a publicity coup and a rallying cry.

2011 - Tory MPs call for a referendum

The Commons Speaker John Bercow announced the result of the vote by MPs

Some 81 Tory MPs defied Prime Minister David Cameron to vote in favour of an EU referendum in October 2011.

Mr Cameron easily won the vote, with Labour support, but leaving the EU - as one of a range of options - was now firmly on the agenda at Westminster. Mr Cameron would announce plans for a referendum just under two years later.

2014 - UKIP runs riot

UKIP's Suzanne Evans in the 2014 election campaign

Nigel Farage had finally found a way to turn the latent Euroscepticism in large sections of the British public into electoral gold, as concerns about the flow of migrants from new EU states were added to the traditional cry for freedom from bossy Brussels bureaucracy.

UKIP seemed unstoppable in 2014. It topped the poll in the European elections, with a massive 3.8 million votes - and made further gains in local elections to consolidate the breakthrough it had made in 2012.

Then Mr Farage turned up the heat on David Cameron by unveiling two Tory defectors, Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless, in quick succession, with the threat of more to come.

2016 - Johnson joins the Leave campaign

Boris Johnson was the biggest name to embrace the Eurosceptic cause

David Cameron had been stunned by the number of Conservative MPs who had joined the Leave campaign, not realising the depth of Eurosceptic feeling in his party.

But he had not expected Boris Johnson to join the cause. The official Leave campaign wanted nothing to do with Nigel Farage over fears he would scare off floating voters.

Its recruitment of Mr Johnson - one of the biggest, and most popular, names in British politics - was a game changing moment. Euroscepticism had finally shaken off its reputation as an eccentric fringe movement.

Recalling UKIP's early days in the European Parliament in 1999, at a farewell press conference in Brussels on Wednesday, Mr Farage said: "We were considered pretty odd. Perhaps we were, I don't know, certainly very eccentric.

"And as those years went by I did begin to wonder whether I might become the patron saint of lost causes."

But now, he added, "far from being a minority sport, Euroscepticism had become the mainstream, settled view in the United Kingdom".