The tough questions facing the UK and US

- Published

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace publicly aired his view on US/UK cooperation in the Sunday Times

Suddenly, the government and opposition are preoccupied with the head-achingly existential questions: "What are we here for? And where are we going?"

These are tough questions to be sure, which probably explains why, on both sides, there's a natural inclination to bring them up and then rapidly change the subject.

After all, how could this, or any, government clearly map the UK's redefined role in the world outside the EU after Brexit?

And how to deal with a US president who happily describes the relationship as "special" - except on those occasions when he appears to forget, or maybe lacks the time or inclination to show he means it?

So, it was striking to see Defence Secretary Ben Wallace publicly airing his view in an interview with the Sunday Times, external, saying the UK could no longer assume it would always be at America's side in any future conflict.

He cited the US' withdrawal from Syria, and President Trump's assertion that Nato should be more involved in the Middle East.

"What is shown is that the assumptions of 2010, that we are always going to be part of a US coalition on everything, is really just not where we are going to be," he said.

Mild rebuke

That seemed a blunt recognition of reality. After all, President Trump had not informed, let alone consulted, Boris Johnson before ordering America's act on Iran's second most powerful man.

British ministers subsequently endorsed the US' right of self-defence.

But the president also threatened to meet any Iranian retaliation with a counter-strike at culturally significant targets, which sounded as if he was contemplating something that is considered a war crime under international law.

That idea was subsequently damped down by US officials, who insisted there would be no American breach of international law.

And on my BBC Radio 5 Live programme, Pienaar's Politics, Security Minister Brandon Lewis echoed the implied, mild rebuke.

"Cultural sites are protected," he said. "We've made that very clear."

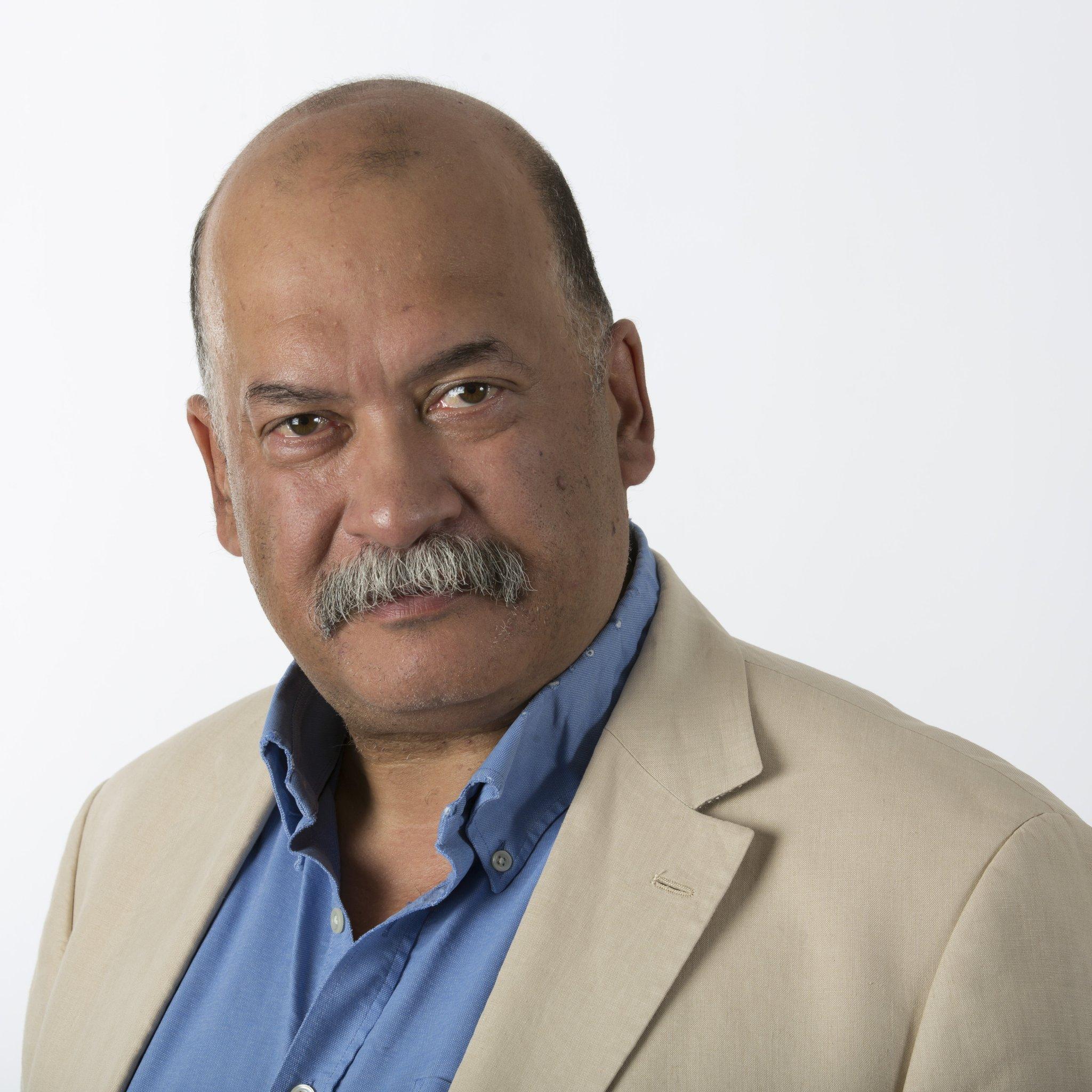

Brandon Lewis said he was sure the special relationship will continue

Regarding any potential conflict in which the UK might need to engage without US military support, the minister would only say, again and again, that he would not entertain "hypothetical questions".

He added: "We're very fortunate our prime ministers and their presidents have often had a really good and strong relationship, as we do now.

"But it goes beyond that. Our special relationship is actually founded on defence and security and that's something... that I'm sure will continue."

Maybe so. But that presumption sounded as if it pre-dated the Donald Trump presidency.

Does anyone seriously believe the Johnson-Trump relationship remotely compares to that of Blair and George W Bush, or Thatcher and Reagan?

Churchill and Roosevelt would surely be an unfair comparison. It was a very different time, though President Obama at least went out of his way to hang out with David Cameron, munching hot dogs together courtside at a basketball game.

'Putting ourselves down'

Speaking to me on 5 Live, Brandon Lewis chose to rely on the comfortable assumption that close UK-US links were a given.

He refused to entertain the notion that one price of Brexit might be a loss of strategic clout if and when EU members act as a political caucus within Nato.

"As the fifth biggest economy in the world and one of the biggest contributors to Nato, and the part we play in both security and defence around the world, we should stop putting ourselves down," he said.

I resisted any temptation to apologise for raising the question.

Gradual process

As for the Labour opposition, Emily Thornberry - the leadership candidate who has struggled to muster the necessary 22 nominations from MPs - came close to suggesting her party should consider rewriting major elements of its policy programme after its disastrous defeat, but did so hesitantly.

Labour should be having a "conversation" with the privatised utilities about alternatives to renationalisation, she told me, adding: "We need a much better service from both."

Sir Keir Starmer and Emily Thornberry are two of the candidates running to be the next Labour leader

Sir Keir Starmer - the front-runner and a Labour centrist - has defended his party's radicalism, and cautiously urged the party not to "over steer" away from the course set by Jeremy Corbyn.

Perhaps when it comes to telling Labour members what many prefer not to hear, he feels less is more. If so, who can blame him.

If Labour does choose to change course though, it will clearly be a gradual process.

Better not expect any dramatic change of direction, at least not now. Not during a leadership election.