Labour leadership: A century of ups and downs in charts

- Published

The new Labour leader faces a huge task. The party's performance at the 2019 General Election was its worst since 1935.

Battered over Brexit, losing support in previous strongholds, and led by Jeremy Corbyn whose personal ratings were among the lowest ever recorded, Labour took a hammering.

Can the new leader turn around the party's prospects?

Here's what 100 years of voting tells us about the scale of the task ahead.

Labour had its first prime minister in 1924

More than 700 million votes have been cast in UK general elections since 1918, some 300 million of them for Labour.

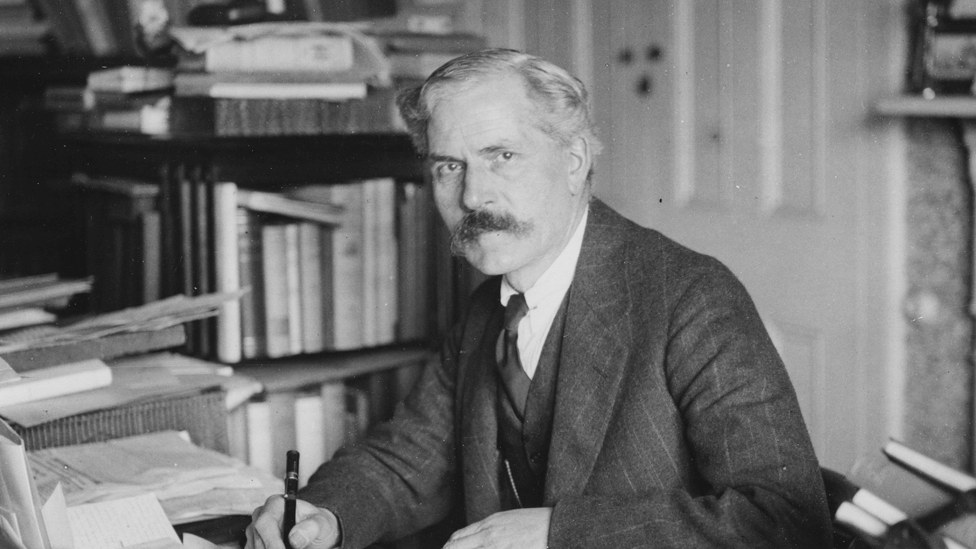

The party produced its first prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, at the head of a minority government in 1924.

Labour's first Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald

Since then Labour has won eight general elections and produced five more prime ministers: Clement Attlee (1945-51), Harold Wilson (1964-70 and 1974-76), James Callaghan (1976-79), Tony Blair (1997-2007) and Gordon Brown (2007-10).

Labour is as weak now as it was in the 1930s

The 2019 general election was a disaster for Labour, leaving Jeremy Corbyn's party with 202 out of 650 Commons seats.

Labour's new leader will have fewer colleagues in the House of Commons than any Labour leader has had for 84 years.

The party lost heavily, even in areas where working class supporters had kept Labour afloat for generations.

Former mining communities in north-east England and Wales turned away. The party lost seats in every English region except London.

In Scotland, Labour, with just one seat out of 59, have been all but wiped out.

Labour has suffered heavy defeats before

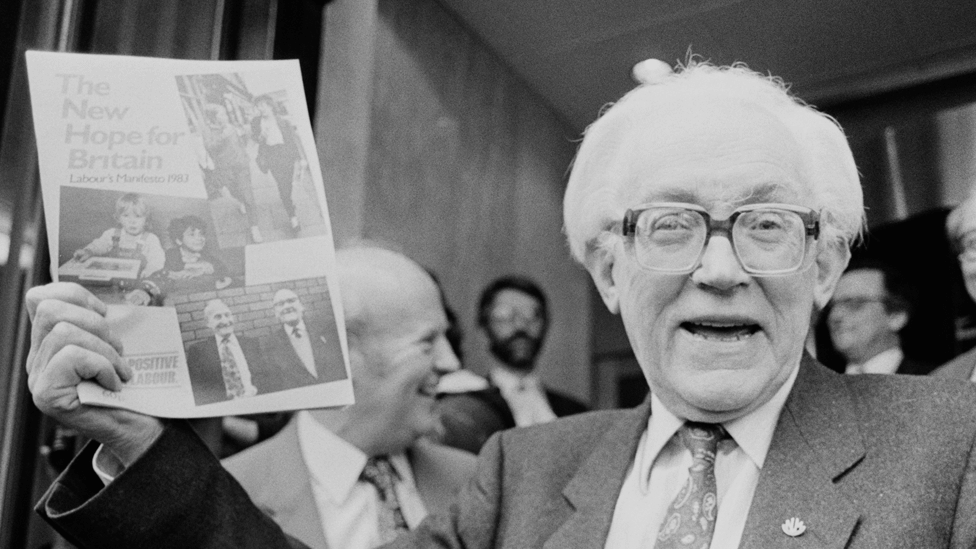

In 1983 Labour, under Michael Foot, won just seven seats more than its current tally.

Labour's poor performance followed a damaging split which resulted in the formation of the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

As in 2019, Labour faced sharp criticism over a manifesto widely regarded as too radical. Critics called it "the longest suicide note in history".

Michael Foot with Labour's 1983 manifesto

Mr Foot also faced Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was riding a crest of popularity, buoyed by victory in the Falklands War against Argentina.

Labour has made some big come-backs

The outlook for the new leader may look bleak, but Labour has recovered from heavy defeats before.

After 1983, it took the party a further 14 years to return to power - in 1997, Tony Blair won a landslide victory.

The result ended 18 years of Conservative rule under Mrs Thatcher and John Major, and gave Labour 418 seats.

Tony Blair went on to win two more elections in 2001 and 2005. In electoral terms, he is the most successful leader Labour has ever had.

Labour under Mr Blair and Gordon Brown was in power for 13 years.

Tony Blair won three elections for Labour: 1997, 2001 and 2005

Similarly, in 1945 Labour overcame huge challenges to win with a substantial majority.

The Conservative Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, had just led the country to victory over the Nazis.

The election took place less than two months after the end of the fighting in Europe.

The Labour leader Clement Attlee mounted a hugely successful campaign for a programme of post-war rebuilding.

Labour leader Clement Attlee won a landslide victory in the 1945 general election

His 145-seat majority, Labour's first, enabled Mr Attlee to introduce a sweeping programme of reforms, including the introduction of the National Health Service.

What are the possible routes back to power?

Analysis from Peter Barnes, BBC Senior Political Analyst

Probably the "simplest" way to win would be to recapture most of the seats Labour has lost since the last victory in 2005.

These charts show that the parts of the UK where Labour has fallen back most are Scotland and the Midlands - definitely not London where the party has actually grown stronger.

A huge difficulty with this would be finding a leader, and policies, that could attract voters lost to the Conservatives on the one hand, and the SNP on the other.

It would just about be possible to do it without Scotland - Tony Blair always had a majority of English seats - but that would require significant gains across the Midlands and the north of England - plus some parts of the south.

A third route, but perhaps the least plausible, is a major realignment where Labour won swathes of southern England which the party has never held before.

Whatever strategy the new leader chooses, they have a massive task ahead of them.

Scotland and south-east England are a big challenge

If Labour is to make big gains next time, the historical record suggests they are unlikely to come in south-east England.

At no point in the past 100 years has Labour won a majority of the seats there and the Tories have dominated almost the whole region.

Tony Blair and Clement Attlee made some gains, but even they were limited.

Hugh Gaitskell, who was leader from 1955 to 1963, Harold Wilson (1963-76), James Callaghan (1976-80) and Neil Kinnock (1983-92) made little impact.

Labour leaders from Ramsay MacDonald in the 1920s right up to Ed Miliband in 2015 saw Scotland as fertile ground.

Even Michael Foot took 41 seats there in 1983.

The Scottish National Party (SNP), which was founded in 1934, made some gains in the 1970s but took just two seats in 1983.

It could hardly be more different now. The outlook for the new Labour leader in Scotland is bleak.

Since 2015, the SNP under Alex Salmond and then Nicola Sturgeon has dominated almost completely. Labour was almost wiped out in 2015.

It made a small comeback in 2017, but was almost wiped out again in 2019.

Labour needs to win back constituencies in north-east England

In England, the north east has been Labour's most loyal stronghold.

Former mining communities and other predominantly working class areas voted Labour in large numbers from the party's earliest days.

But even here the Tories made significant gains in 2019.

The Conservatives have a higher proportion of north-east England seats than at any time since 1935.

Bringing constituencies like Blythe Valley, a Labour seat from 1950 to 2019, and Bishop Auckland, Labour from 1935 to 2019, back into the fold will be a major challenge for Labour's new leader.

The Conservative government under Boris Johnson has signalled it will fight hard to stop that happening.

London and north-west England may offer some hope

London could be an exception for Labour and its new leader as the capital remains a predominantly Labour city.

In 2019 the party performed there as well as it has in any election since 1950, except when Labour was led by Tony Blair.

Holding on to seats in London may be an easier task for the new leader than extending support outwards from the capital.

Likewise the north west of England could be more fertile ground for the new Labour leader.

The party lost seats in this region in 2019, but still holds more than half which is a higher proportion than it held during most of the 20th Century.

Methodology and caveats

We analysed data from every general election since 1918 held by the House of Commons Library.

Each election occupies the same width on the graph.

We did not include by-elections.

Data for Northern Ireland were available from 1922 onwards.

There have been numerous changes to constituency boundaries and changes in the number of seats in the House of Commons since 1918.

The height of each nation or region in the charts is proportional to its current number of constituencies. So Scotland occupies 59/650ths of the graph and Northern Ireland occupies 18/650ths of the graph height as they currently have 59 and 18 constituencies respectively (out of a total of 650).

That height is divided between all the seats that were fought in a given election.

We have gathered some parties into one category, for example the Liberal Party and the Liberal Democrats or Labour and Independent Labour.

Prior to 1974, Ulster Unionists are listed in the House of Commons data as Conservatives as they took the Conservative whip.

We have also excluded the small numbers of university seats which existed before 1945 and second seats from the two-seat constituencies that existed before 1950.

Neither significantly alters the proportions shown in the charts.

Data analysis by Felix Stephenson. Design by Sean Willmott.