Post-Brexit deal: What's happening in the UK-EU talks?

- Published

Negotiations on the post-Brexit relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union are looking a lot like the negotiations on the Brexit withdrawal agreement last year.

Each side says the other needs to make a move. And if there is to be a deal, it will probably come at the eleventh hour.

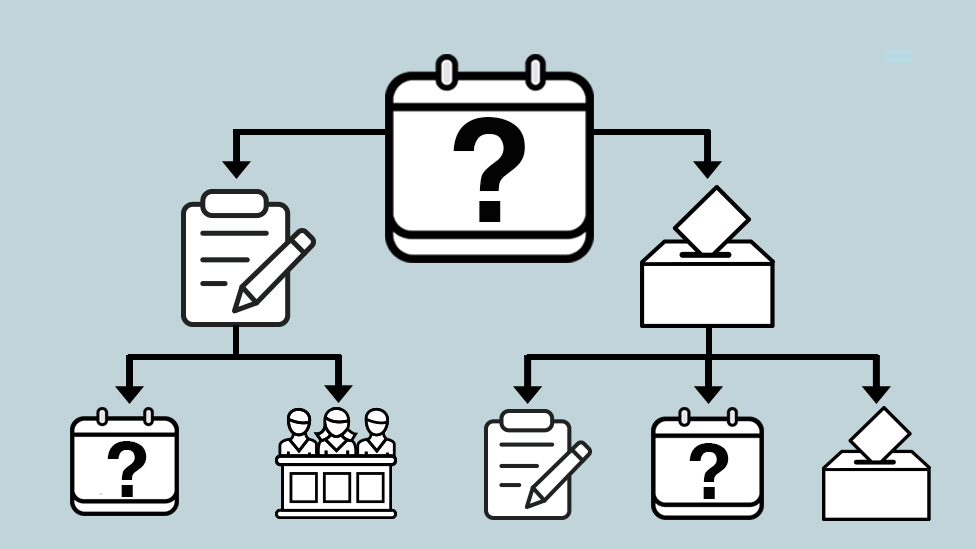

That means compromises will have to emerge in September before a deal is agreed in October - leaving both sides just enough time to ratify an agreement before the end of the year.

There have been suggestions of potential progress this week - on the role of the European Court of Justice and on the overall structure of a future agreement.

But differences between the two sides are substantial, and go to the heart of what the Brexit process is all about: how closely aligned will the UK be with the EU in the future?

For the UK sovereignty is key; for the EU the priority is to protect the integrity of its single market.

And for now, the two sides often seem to be talking past each other in public.

When asked whether the talks are closer to breakthrough or breakdown, a senior UK official involved in the negotiations said they were "potentially equally close to both".

"I can quite see how we could make a breakthrough relatively quickly if they (the EU) adjust their position."

But for Michel Barnier, the EU's chief negotiator, the boot is on the other foot.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

"By its current refusal to commit to conditions of open and fair competition and to a balanced agreement on fisheries," he said, "the UK makes a trade agreement - at this point - unlikely."

Mr Barnier insists that EU positions on difficult issues are not tactical, but are designed to protect the EU's long term interests.

But his UK counterpart, David Frost, makes exactly the same point about the UK's stance.

"We have always been clear that our principles in these areas are not simple negotiating positions," he said, "but expressions of the reality that we will be a fully independent country at the end of the transition period."

Spoiler: this is the kind of thing trade negotiators always say.

But both sides will soon have to decide when and how they wish to compromise, or whether they are willing to walk away.

The UK had hoped that more progress might have been made this month, but that was always unlikely. The EU had too many other things on its mind.

EU leaders have just emerged from a marathon five day summit focussed on an economic recovery fund for coronavirus, and on the EU's budget for the next seven years. Those things are more important to them than trade with the UK, and had to be dealt with first.

Officials from Germany, which currently holds the EU's rotating Presidency, have made it clear that they will be focussing on trade talks with the UK in September and October.

So, while negotiations will continue in August - and progress could be made in a number of areas - the most difficult issues will still be up for debate in the autumn.

The pressure of time is a big factor, because the post-Brexit transition period expires at the end of this year.

But the mood music is also important. While Boris Johnson's government sees Brexit as an opportunity, the EU still sees it as a mistake to be managed, and that has implications for these negotiations.

Normally if you do a trade deal you celebrate opening up markets, and making trade a bit freer. This proposed deal is all about the extent to which trade between the UK and the EU will be less free than it was before.

And that is more difficult to get excited about.

Michel Barnier and David Frost lead negotiations for the EU and the UK

But, despite some gloomy headlines in British newspapers this week, there is an additional factor to take into account.

Usually if trade negotiations fail, things stay as they are. In this case, though, a breakdown in talks will lead to sudden and substantial changes in the economic relationship between the UK and the EU.

There will be some changes at UK borders anyway, deal or no deal. That will be a challenge.

But on both sides of the Channel, businesses that are already struggling with the coronavirus are desperate for a degree of certainty to be delivered by their political leaders.

And that is one reason to believe that compromise can still be found, and a deal of some kind - however imperfect - can still be done.

- Published13 July 2020

- Published29 June 2020

- Published26 January 2024