Reflections on the Pandemic Parliament

- Published

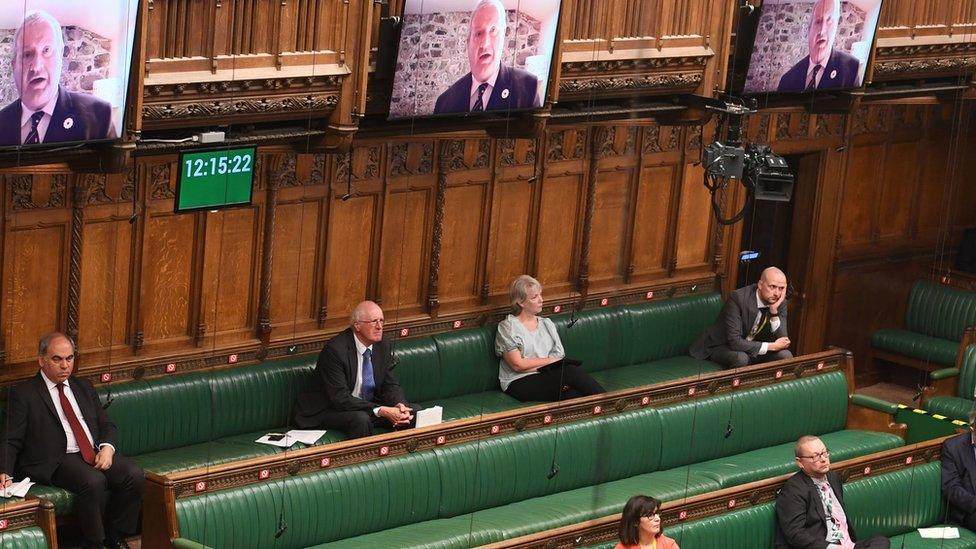

Parliament is in recess, with MPs and peers due to return to Westminster in the first week of September.

The Commons and Lords have both seen a tumultuous few months since they returned after the general election last December.

But what have been the defining trends from the 2020 Pandemic Parliament?

Rebel, rebel

It's a legacy of the battles over Brexit and before that, Iraq, and the strains on both the major parties, that backbench awkward squaddies and ad hoc alliances across the parties have become a habit in the Commons.

And the election in December of the first substantial single-party majority since Tony Blair's third win, in 2005, has not put an end to it.

During the Coalition years, and then when David Cameron enjoyed a micro-majority, and still more after Theresa May lost it, different factions - Brexiteers, Remainers, and assorted other alignments - have learned how to put governments under pressure and regularly win the day.

Virtual working during the pandemic is yet to sate an appetite for rebellion in the Commons.

Take the first, unsuccessful, Tory rebellion over the UK incorporating technology from the Chinese company Huawei into its 5G network, back in January.

This allowed me to make a nostalgic return to the wonderful CommonsVotes app, which had proved an indispensable tool in covering the Brexit battles before the election.

The key amendment, proposed by former Conservative leader Sir Iain Duncan Smith, was supported by an eclectic cross-section of dissidents.

The group ranged from old Maastrichtistas like IDS himself and European Research groupies, including the new Chair Mark Francois, to One Nation types like the former "de facto deputy prime minister" Damian Green, to select committee chairs like Sir Bob Neill, William Wragg and Tom Tugendhat.

There were veteran Thatcherites, Cameroon holdovers, plus hardened heavyweights like David Davis and the chair of the 1922 Committee, Sir Graham Brady.

There were even a couple of new intake MPs in James Davies and Anthony Mangnall (who may well find themselves spending long hours pondering particularly tedious statutory instruments, if the whips take their revenge).

The week before, there might have been a minor rebellion over HS2, but it was headed off, and in any case, could have been dismissed as constituency-driven. So misalliance, or new alignment?

This felt dangerous - it was senior MPs directly questioning the government - and the PM's - judgement over something pretty central to governing, an issue of national security.

And, a few months later, they got their way - when the government announced kit from Huawei is to be banned from the UK's 5G network.

The lesson will be learnt and applied to other discontents, of which there are now a number.

Which brings me to…

The delights of trade deals

The whole point of Brexit was to free the UK to enrich itself with new trade deals across the globe.

But free, or freer trade is a two-edged sword; some parts of the economy win, as new markets are opened up for, say, steel and ceramics, while consumers could get access to cheaper products, but others can be opened up to tougher competition.

This is a particular issue for farmers, who fear being undercut by foreign producers who're not required to meet the UK's animal welfare and environmental standards.

The government promised in its election manifesto, that this would not happen - but the devil will be in the detail of new trade treaties as they are negotiated, which means scrutiny in Parliament will be critical.

The Trade Bill before Parliament at the moment is mostly about rolling forward the existing relationships the UK had as a member of the EU (which include such guarantees), but the government whipped against attempts to write the guarantees into the Bill itself.

And they also defeated attempts to require the Lords and Commons to approve the negotiating mandate for trade talks in advance, which would have given a preliminary airing to such concerns.

Little traction

Ministers will have a far freer hand than they would have had under the previous version of the Bill, where Theresa May had made considerable concessions to her rebels; these have now been wound back.

All this leaves MPs and peers with startlingly little traction over what could be very significant treaties, especially compared to legislators in other parliaments.

In the authoritative verdict of the House of Commons Library, the government now "has no obligation to inform or consult Parliament".

Parliament, the Library added, has "no formal role, structures or procedures" for scrutinising treaties, it does not have to debate them or approve them, and has only a "limited and as yet unused power" to delay ratification, in addition to passing legislation where required.

So it will be for any MPs with concerns to use devices such as Parliamentary Questions, debates and select committee inquiries.

And this is where the existence of those hardened bands of parliamentary guerrillas comes in...

Select committee titans

Jeremy Hunt is one of a clutch of former ministers now sitting on the backbenches.

The chairs of Parliament's select committees will be increasingly important players in all this.

The influx of ex-ministers, including some very senior ones, into the top jobs on the Committee Corridor has boosted the committee system's already increasing clout.

There had been concern that they would treat committee chairs as a convenient resting place before returning to office, and would therefore be cautious about holding current ministerial feet to the fire.

Cross-party working

But the likes of former Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt, former Treasury Minister Mel Stride and former Business Secretary Greg Clark have proved ready to give current ministers a tough time in their scrutiny of the handling of the pandemic, and on other issues too.

It is also noticeable that the committees have been generating amendments to legislation - like the new clause to the Agriculture Bill on equivalent standards for imported food signed by members of the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee, including its Conservative Chair, Neil Parish.

It's not a big leap from the kind of cross-party working seen in committee rooms to the same people cooperating on the same issues in the Commons Chamber.

- Published14 July 2020

- Published19 January 2018

- Published26 January 2024