A-levels: How did Gavin Williamson survive exams U-turn?

- Published

The career aspirations of many teenagers were delivered a blow last week when 40% of A level results in England were downgraded from teachers' assessments.

So why are the career prospects of Gavin Williamson - the education secretary who presided over what even some usually supportive newspapers have described as a "farce" or a "humiliation" - not in tatters?

It's not just some students, teachers and parents who are scratching their heads over this question - but some Conservative MPs too.

One of them said to me: "Any minister who makes children cry is not in a good place."

Another pointed out that he had plenty of time to prepare for how students should be assessed - exams were cancelled five months ago, on 18 March.

Yet Downing Street maintains the prime minister has full confidence in Gavin Williamson.

Why?

One reason is that he has a "human shield," in the form of England's exam regulator, Ofqual.

Right questions, wrong answers?

The case for the Williamson defence is, essentially, that he was asking the right questions of the regulator but was getting the wrong answers.

It should be said that it was the education secretary himself who decided in March that he did not want to see "grade inflation" as a result of teachers' assessments - and that this year's results would have to be "moderated" or "standardised".

Mr Williamson claims that the principle of "moderation" was widely accepted - and that in more normal times there would always be pupils who failed to meet teachers' expectations in real exams.

The Department for Education argues that there was also widespread consultation over the criteria Ofqual would deploy when standardising the grades.

So the only issue was how that standardisation would be conducted rather than any debate over whether it was right in principle.

Alarm bells

Alarm bells about the effects of standardisation were loudly rung by the cross-party education committee - under the chairmanship of Conservative MP Rob Halfon - on 11 July.

Committee members called for more transparency over the algorithm Ofqual was using to standardise grades - and demanded that it be published immediately to allow for proper scrutiny.

The algorithm was not made public until last Thursday.

The committee also warned, external that Ofqual's model "does not appear to include any mechanism to identify whether groups such as black and minority ethnic (BAME), free-school-meal-eligible pupils, children looked after, and pupils with special educational needs have been systematically disadvantaged by calculated grades".

Gavin Williamson's allies say he took these concerns seriously.

Students in Mr Williamson's constituency stage a protest

Schools minister Nick Gibb and education department officials met the senior figures at Ofqual on 16 July and pressed for clarification on how the algorithm would impact pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds and from ethnic minority communities.

Officials maintain that the correct questions were asked and that they received assurances that those from disadvantaged backgrounds would not be adversely affected.

One insider said that the education secretary can probe Ofqual on its methods but can't, of course, design an algorithm himself.

But Mr Williamson was aware that the algorithm's use was likely to throw up "hard cases" and "outliers" - rather than masses of students - who would not get the grades they deserved.

So the education secretary focussed on improving the appeals system and, ultimately, ensuring that it was free to use, officials say.

Ofqual have yet to respond to inquiries about the meeting.

An appealing system?

In its July report, the education committee said: 'We are extremely concerned that pupils will require evidence of bias or discrimination to raise a complaint about their grades.

"It is unrealistic and unfair to put the onus on pupils to have, or to be able to gather, evidence of bias or discrimination. Such a system also favours more affluent pupils and families with resources and knowledge of the system."

There has been widespread concern about the fairness of the "calculated" results

Education department insiders maintain that Mr Williamson - who went to a comprehensive school - was determined to inject fairness in to the system and create a robust (one of his favourite words) safety net to catch anyone caught out by the system.

Indeed, there was still wrangling going on between Ofqual and the department as recently as last weekend over further changes to the process.

Ofqual guidance on how to appeal was removed from its website around eight hours after it first appeared.

And they say that it became apparent only in the past few days that the appeals system, however "robust", could not deal with the potential scale of the problem.

Class conflict

Last Tuesday, the Scottish government had to perform a U-turn under pressure.

An analysis by Ofqual's Scottish equivalent - the SQA - showed that pupils from deprived backgrounds were subjected to higher rates of downgrading than those who were better-off.

Scottish education secretary John Swinney insisted that the SQA standardisation model was fair - but that he was now moving to teacher assessments because of the "anguish" some pupils had experienced.

Gavin Williamson's allies say that he sought assurances from Ofqual that the problems the Scottish system had highlighted would not affect England - and, once again, he received assurances that this was the case.

Only when the results came out on Thursday did the outcome begin to look rather too familiar.

Initially, it was assumed there were rather a lot of "outliers" and only subsequently was it established that the algorithm itself was flawed.

Over the weekend, there was an internal debate at the DfE over whether the algorithm could be improved, or whether teachers' assessments would have to be accepted after all.

Neither solution was ideal.

What seems to have swung it is that fixing the algorithm would have led to a delay to this week's GCSE's results.

This was not something Downing Street wanted to see.

I'm told that by the time the education secretary and the prime minister spoke - by phone - on Monday morning, they were, metaphorically at least, "in the same place".

It would have to be teacher assessments as the least worst option, and the announcement would be made later that day.

The case for the prosecution

What is frustrating some Conservative MPs is not the U-turn itself, but the time it took to put into action.

Some privately accuse the education secretary of not being robust enough in interrogating Ofqual earlier in the process.

Some wonder why offers from the Royal Statistical Society to help with the modelling in April weren't accepted.

But what is agitating most of the education secretary's internal critics is that it took nearly a week for the U-turn in Scotland to be repeated in England.

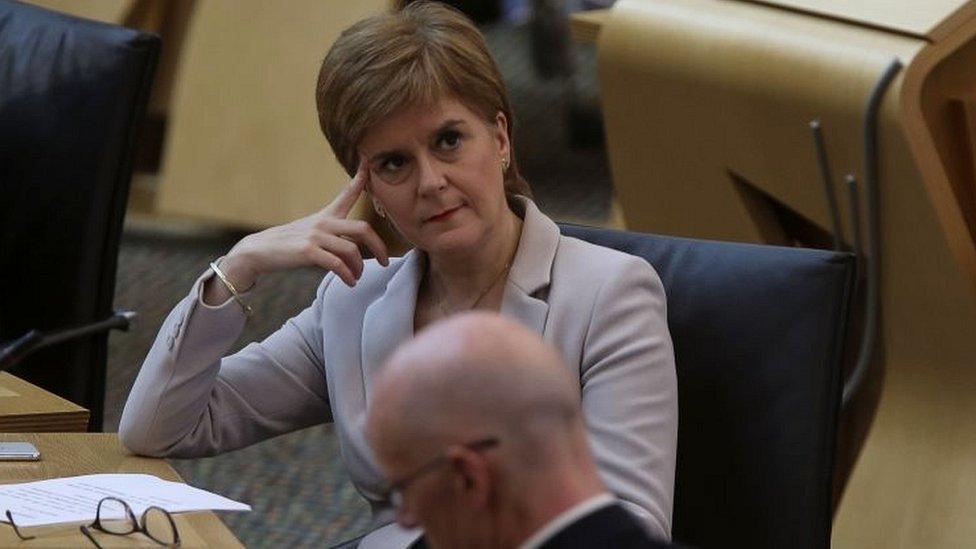

John Swinney survived a no confidence vote in the Scottish Parliament

They feel Gavin Williamson dug himself in to a hole by denouncing so strongly the actions of the Scottish government, highlighting the "unfairness" of taking teachers' predictions solely as the basis for results.

This was, arguably, a failure of the education secretary's political antennae.

Even if the Ofqual algorithm did not discriminate against the most disadvantaged, it should have been possible, critics maintain, to anticipate that the protests and parades of disappointed students in Scotland would be repeated in England, given that a similar scale of downgrading was to take place.

The perception that a government committed to "levelling up" the nation was downgrading bright students from underperforming schools was toxic.

And some MPs are questioning why, in the Times, external, as recently as Saturday Gavin Williamson was praising what was "a fair and robust system for the overwhelming majority of students".

And declaring there would be "no U-turn, no change".

And on Sunday, when internal debates over accepting teachers' assessments and abandoning the option of fixing the algorithm were very active - why was he apparently defending "the calculated grade overseen by Ofqual", in the Express newspaper, external.

A former minister with a background in education told me that because the education secretary had nailed his colours so firmly to a teetering mast, it was "inevitable" that he would have to go.

But it seems nothing is inevitable in politics.

Boris Johnson himself is not seen as devoid of blame by some of his own MPs.

Last Thursday, the prime minister was also defending the "robust" system of assessment in England.

The PM said last Thursday results were 'robust, good, dependable'

As one MP put it, "the captain of the ship was too hands off".

Indeed - for some - that captain changed direction as though he were on the bridge of an oil tanker, when what was required was the swift launching of the lifeboats.

How safe is Williamson's job?

One former Conservative minister said he fully expects Gavin Williamson to be moved in any autumn reshuffle - that he has been given a reprieve by Downing Street, not exoneration.

He has to sort out the messy challenge of getting newly upgraded students in to universities then the tricky task of getting pupils in England back to school next month.

The partial return prior to the summer wasn't exactly smooth.

So if Mr Williamson's performance in those areas falls short, then his current job is not safe in the long term.

But there are other reasons why he hasn't received a ministerial P45.

This is not an administration which does resignations.

Boris Johnson is loyal to those who are loyal and useful to him.

The clamour amongst Conservative backbenchers for his adviser Dominic Cummings to go over his lockdown trip to Durham subsided as Downing St dug in its heels.

The controversy over the Richard Desmond planning decision has not cost housing secretary Robert Jenrick his job.

And Gavin Williamson has been helpful to Boris Johnson behind the scenes - as he was to Theresa May until he was sacked, and got behind Mr Johnson's leadership bid.

A former chief whip, his reputation as a minister may have suffered but not his abilities as a fixer.

No 10 may want to retain him inside the tent.

But he also has some cover in the current controversy.

He U-turned - but so too did the SNP administration in Edinburgh, the Labour-led administration in Cardiff and the power-sharing DUP/Sinn Fein executive in Belfast.

As is important in times of personal crisis, he is not alone.

The question is whether the exams saga has predominantly dented Mr Williamson's credibility - or that of the entire government.

With a majority of eighty and probably four years until the next election, that's not a question to which Boris Johnson needs an immediate answer.