Coronavirus: Why have there been so many U-turns?

- Published

Let's start with an obvious point: governing in an unprecedented global pandemic is not simple.

When coronavirus hit many of the government's plans went out the window. Ministers were forced to react quickly to events many of us could never have imagined a year ago when Boris Johnson became prime minister.

But it's also pretty obvious that the government has changed its mind a lot in the last few months.

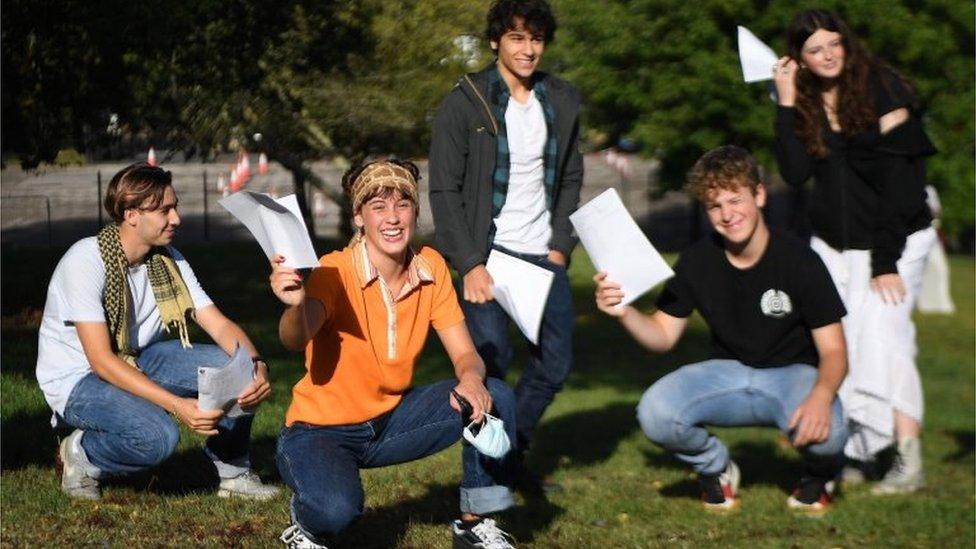

In the last fortnight, over A Level/GCSE results and face coverings in schools, the position has changed significantly in a matter of hours.

That's led to real concern among some Tory MPs that some ministers just don't have a grip at the moment.

On Tuesday, as it became clear the government was going to change its position on face coverings, I was on the phone to one senior Tory backbencher who wondered in despair: "What the hell is going on?"

Behind the scenes, it wasn't clear at all.

I've been told Education Secretary Gavin Williamson briefed some people in the education sector on Tuesday afternoon that England was set to follow a model very similar to Scotland, who had just announced face coverings would be compulsory in communal spaces in high schools.

But after that emerged, a number of Conservative MPs made their opposition clear. Ministers ultimately settled on a policy focused on coronavirus hotspots, with discretion for head teachers elsewhere.

But there is growing disquiet in the Conservative Party that the government is on the back foot and that policies keep "evolving".

Conservative MP Huw Merrirman told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "I'm sick and tired, and I think many people in the public are sick and tired, the science just changes."

He added: "There comes a point in time where policy-makers have to get a grip on policy, decide what it is, be firm with it, be certain, give reassurance and say 'this is the way we're going to act'."

Mr Williamson said he was "incredibly sorry for the distress" caused to pupils after having to make a U-turn in how A-levels and GCSEs are graded

Some fear the government is reacting to pressure, rather than shaping the response.

Another senior Tory backbencher told me this morning: "It's becoming the currency of this government that we take a position then change it. That undermines confidence."

He added: "We are a government devoid of the confidence to make a difficult argument."

Conservative MPs are expecting a fractious atmosphere when they return to Parliament next week.

The list of examples of the government changing its mind very publicly in recent weeks is long.

To name a few: the NHS health surcharge, the NHS bereavement scheme, the rollout of the "critical" track and trace app, getting all primary pupils back in school before the summer, free school meals during the summer, the results algorithm, face coverings in schools.

There have been big changes in policy when it came to quarantine on arrival in the UK which frustrated MPs too.

Mr Swinney survived a vote of no confidence after exam results chaos in Scotland

This hasn't been unique to Westminster. There have been some really public and discomfiting U-turns elsewhere in the UK too.

Scotland's Education Secretary John Swinney faced calls to resign for initially defending the Scottish government's exam results algorithm - which he eventually junked (one of the criticisms at Westminster is that the UK government didn't learn from the mistakes in Scotland).

Wales and Northern Ireland also had standardisation models they abandoned under pressure too.

Although Scotland led the way when it came to announcing face coverings in schools - just last week Mr Swinney was saying they weren't necessary. It was a U-turn in Scotland as well as England.

The communication of that decision in England was a bit more, well, messy. On Monday, the education secretary and deputy chief medical officer Jenny Harries were playing down the need for face coverings. Just over 24 hours later, the government was announcing its policy change.

Public sympathy?

But how much does it matter?

At Westminster, we report these U-turns as big stories. They cause embarrassment and generate a lot of conversation in political circles.

But some believe that owning up to a mistake and trying to put it right is the best policy.

When Mr Swinney survived a confidence vote in the Scottish Parliament over results, he told MSPs: "These are unprecedented times and, as we have said throughout this pandemic, we will not get everything right first time."

There is some evidence suggesting the public have some sympathy for that approach.

YouGov polls indicate more people viewed U-turns as a good thing (49%) - rather than a bad one (23%) - during the pandemic. Even before the coronavirus crisis, though, YouGov's polling suggests more people saw policy changes as good than bad.

Chris Curtis, political research manager at YouGov, said: "In most cases U-turns by the government don't end up moving the polls.

"If anything, YouGov data shows that people seem to see them as a positive sign that the government are willing to listen and change their mind if people complain or situations change."

The fear some Conservatives have, however, is that a number of U-turns in a short space of time show a problem; not the government is willing to listen, but that it isn't in control.

The government was forced into a U-turn on free school meal vouchers following a campaign by the footballer Marcus Rashford

Some make concessions for changing evidence - and politicians having to react to it. Ministers are given papers from their scientific advisors and they show understanding of the virus developing.

But it's clear that many of these decisions have been political. When Marcus Rashford called for free meal vouchers to be extended to the summer holidays - as many in Westminster were predicting a change of policy - the government initially dug its heels in.

They then changed their mind after Tory MPs registered their disquiet.

Likewise, it was ministers who failed to persuade enough parents and teachers that schools were safe before summer.

Many of these issues may well be forgotten by the time of the next UK election, scheduled for 2024.

But the danger for the government is that the public loses faith that ministers are in control - and loses faith in their decisions.

- Published16 June 2020

- Published26 August 2020

- Published17 August 2020