Civil service shake-up: Rewiring the government machine or blowing a fuse?

- Published

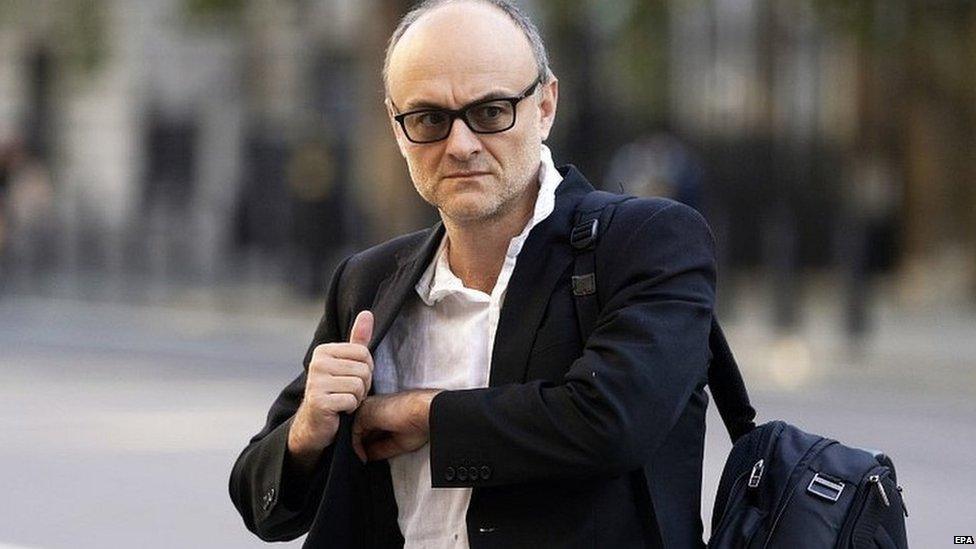

The PM's right-hand man has said the civil service lacks key skills

On a mild Tuesday in early September, after 13 months working at the most famous address in British politics, Dominic Cummings left Downing Street.

The prime minister's chief adviser moved his office into 70 Whitehall, a short walk from his old base in Number 10.

The moment passed without the political hysteria that so often follows Mr Cummings, but the motivations behind it go to the heart of what Boris Johnson's government wants to achieve.

"What you need is a Number 10 where you push a button or pull a lever and things actually happen," says Dr Jon Davis, from King's College London.

"There's nothing more frustrating for a prime minister than the idea that you have the power but nothing actually happens."

By moving Mr Cummings, as well as the Number 10 Policy Unit, Boris Johnson hopes to exert more influence across Whitehall's numerous government departments.

He hopes the new, open plan office space - dubbed the Starship Enterprise - will encourage collaboration and bright ideas, a far cry from the cramped, rabbit-warren corridors of Downing Street.

While the sci-fi nickname might be futuristic, the idea is not.

'Too small'

In 1964, soon-to-be prime minister Harold Wilson told the BBC Radio programme Whitehall and Beyond, "I think that Number 10 is far too small. I think the right thing is to build up the cabinet secretariat to its proper strength."

His answer was to create the Policy Unit, which Johnson and Cummings now hope to reinvigorate.

Harold Wilson was the first post-war prime minister to lament No 10's lack of muscle

Jon Davis says the advisers being hired to make that reinvigoration a reality also hark back to previous government plans: "You look to the 1970s and Edward Heath and you look at the central policy review staff, brought in to think the unthinkable, very similar to the misfits and weirdos that Dominic Cummings wrote about in his infamous blog."

Ministers have also made clear in recent months that a civil service shake-up is on the cards.

In a speech in July, Michael Gove said the UK had, for many decades. "neglected to ensure that senior members of the civil service have all the basic skills required to serve government and our citizens well".

Former civil servant Nadine Smith, who now runs the UK branch of the research company the Centre for Public Impact, thinks Mr Gove's plans hold "real promise".

She believes there's an acceptance that the coronavirus crisis has uncovered issues in the sometimes fragmented way the civil service functions.

"Certainly most civil servants do want to see a Whitehall that is really fit for our times, has the expertise, is connected and co-ordinated and most people understand the need for a strong centre of government at this time too," she says.

"I do think however that more thought perhaps needs to go into how Whitehall can ensure that it doesn't hold on to all the expertise, so that expertise is shared across the rest of government."

Leaving London

That sharing of expertise ties neatly into the government's promise to "level up" non-metropolitan areas of the country. In his speech, Michael Gove questioned why "so many of those charged with developing our tax and welfare policies [are] still based in London".

That's indicative of the second part of the Johnson plan.

At the same time as making Number 10 more influential, he wants to move some parts of government away from the capital, into the regions that gave him a large majority in December's election.

The civil service is too London-centric but experts say relocating officials on its own will not make much difference

Nadine Smith says some regions of the UK are feeling neglected by Westminster-centric politics, but warns against a simple solution.

"I personally don't believe that moving civil servants out of London, on its own as a measure, will be enough to solve the problem of the gap that exists between communities, public sector, local government and central government.

"Moving civil servants into parts of the country must be seen as a welcome move from government, rather than it being seen, which is potentially a danger, as Whitehall moving in to the rest of the country."

'Popping the bubble'

Campaigning to decentralise establishment power has worked across the Atlantic for Donald Trump.

In the 2016 presidential election, he promised to take on government bureaucracy, or as he put it - "drain the swamp".

Donald Trump came to power promising the "drain the swamp" in Washington DC

"Part of this plan of draining the swamp is to get the federal departments out of Washington DC," says Sarah Elliott, chair of Republicans Overseas UK, "to pop that bubble, that Washington DC bubble, and spread out the bureaucracy as well, at the same time shrinking the bureaucracies to make them more nimble and more able to respond to the needs of the American people".

So does she see any parallels between President Trump's "drain the swamp" rhetoric and Boris Johnson's plans to reorganise Whitehall and the civil service?

"Absolutely, I think it's pretty common now around Western democracies.

"They both were elected by working class, non-metropolitan elite voters, so they both have a responsibility to respond to the needs of people who primarily don't live in the South East and London or around a major metropolitan area in the US. So their ways of relating to their electorate will be similar."

Public services

So could similar plans to change the workings of the UK's political institutions be popular here?

"The broad feeling that most people have is that they want things like public services to improve, but they don't really mind how that's done," says Deltapoll's Joe Twyman.

"And so they would say 'yes I want civil service reform', but in a lot of cases what they're saying is, 'I want reform, I want things to improve, I want changes to take place'" but "they're not really so interested in the precise nuances of what that reform is".

While the intricacies of civil service reform may not excite the public at large, several high profile departures have made headlines this year.

They included the stepping down of Sir Mark Sedwill, the now-former head of the civil service.

He's been replaced by the less experienced Simon Case and unsurprisingly, those comings and goings have caused some unease in the ranks.

One former permanent secretary says while the government may have diagnosed a problem, it's still not clear whether they know what the solution is.

"There are no details on what the projects are," they say. "How is this reform going to work?"