Why the PM's devolution 'disaster' comments matter

- Published

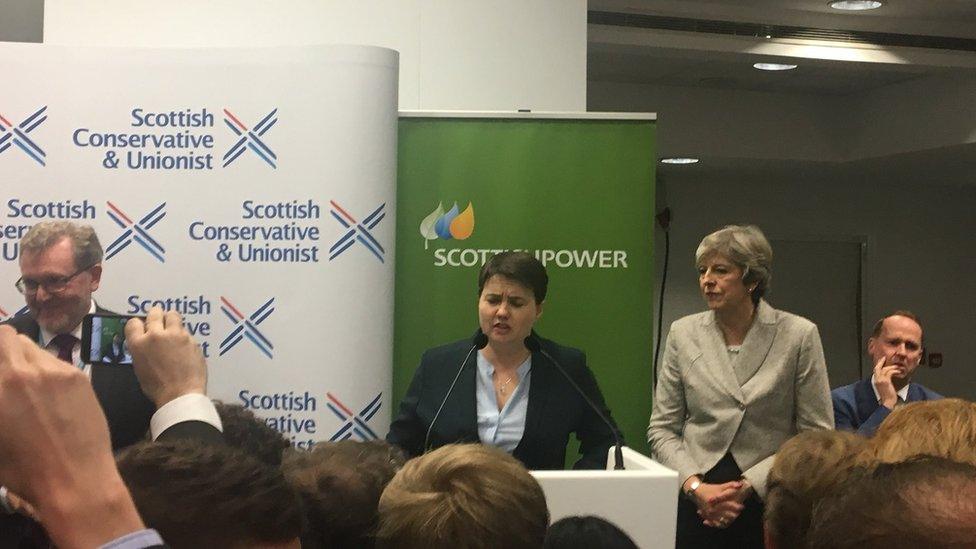

Mrs May and Ms Davidson spoke to a gathering of Scottish Conservatives at the party's conference in 2017

Sunday 1 October 2017 in Manchester.

Prime Minister Theresa May stands beside Scottish Tory leader Ruth Davidson at a fringe meeting at the Conservative conference.

Moments later, Mrs May held Ms Davidson's hand aloft and, in a rare display of euphoria, shouted into a microphone: "Together we saved the union".

Things have changed since then.

In 2017, the Scottish Tories had just had their best general election result in years.

Mrs May and Ms Davidson were close - and on the same page when it came to tactics over independence.

Ms Davidson was invited to cabinet meetings to talk about the issue.

Fast forward to now and the relationship between Scottish and UK Tories is strained.

In recent months, the Scottish Tories have been trying to distance themselves from Boris Johnson - and the new Scottish Tory leader Douglas Ross has launched some thinly-veiled attacks on senior Tories in London, accusing them of defeatism and disinterest when it comes to the union.

Many, he has warned, want a UK government focussed on England.

Mr Ross has cast doubt on whether the PM is an asset to his party in Scotland.

Douglas Ross pictured with Boris Johnson in 2019

That relationship will not have been helped by the prime minister telling MPs privately that devolution had been a disaster.

No 10 has insisted he is a fan of devolution - he was London mayor, of course - but not when it's "used by separatists and nationalists to break up the UK".

But Mr Ross was forced to come out and say the PM doesn't believe devolution is a problem and to urge against "distractions".

There are many in Whitehall who find devolution tricky.

There are more still who believe Nicola Sturgeon has communicated well during the pandemic - and that's increased support for independence.

There are some in Tory circles who remain sceptical about devolution and think it has given nationalism a platform.

But very few in the public eye would argue against the Scottish Parliament.

Nicola Sturgeon has responded to the comments by Boris Johnson

And the timing of this row is far from ideal for Conservatives in Scotland.

In six months, there will be another crucial Holyrood election.

The SNP look set for a landslide win - based on a number of polls - and will use that victory to demand another independence referendum.

As we've reported before, the UK government strategy is to argue Scotland is served well by having two governments, talking up more of what the UK government does, particularly through the Treasury - in essence, that devolution works.

But the SNP Scottish government have argued for months that the UK government wants to interfere in devolved issues - they call the Internal Market Bill a "power grab" which will undermine devolution, for example.

And now, for the next few months, they are likely to point to Mr Johnson's words as an example that Whitehall doesn't like devolved governments having power.

Independence supporters will also point to 2014 - where Holyrood was promised extensive powers if Scotland rejected independence.

It has had more powers since, but Mr Johnson also said last night that he didn't see the case for further devolution, just at a time when some are saying exactly that could help stop the rise in support for independence.

'It certainly doesn't help'

So, this creates an awkward debate for Scottish Tories which they'd rather not be having.

As one told me this morning: "It certainly doesn't help".

But it also shows just how bitterly divided unionists are.

Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats are absolutely furious with Mr Johnson's comments and have been the most outspoken critics today.

The Lib Dem MP Alistair Carmichael, who was Scottish Secretary in the coalition years at the time of the 2014 referendum, told me for BBC Radio 4's World at One: "Boris Johnson is now, I think, probably the greatest threat to the continuation of the United Kingdom - much bigger than Nicola Sturgeon or Alex Salmond could ever hope to be."

He added: "Let's not pretend this is anything other than a bad moment for those of us who want to remain part of a United Kingdom".

This matters because if there is another independence referendum, it's almost impossible, as things stand, to see Labour and Lib Dem politicians working with Conservative unionists like they did in 2014.

The unionist case is split between those who think the answer is more powers and those who don't.

The SNP has its troubles too.

There are divisions in the party and it's record in government is coming under scrutiny ahead of May's vote. More on that soon.

But it is riding high in the polls and the Conservatives - and other unionists - desperately need to claw back some ground.

Unforced errors do not help - especially from the prime minister.