Liverpool: How one city took on the Covid-19 crisis

- Published

When the prime minister addressed the nation on Thursday following the announcement of England's latest tier restrictions, he reserved much praise for one city in particular.

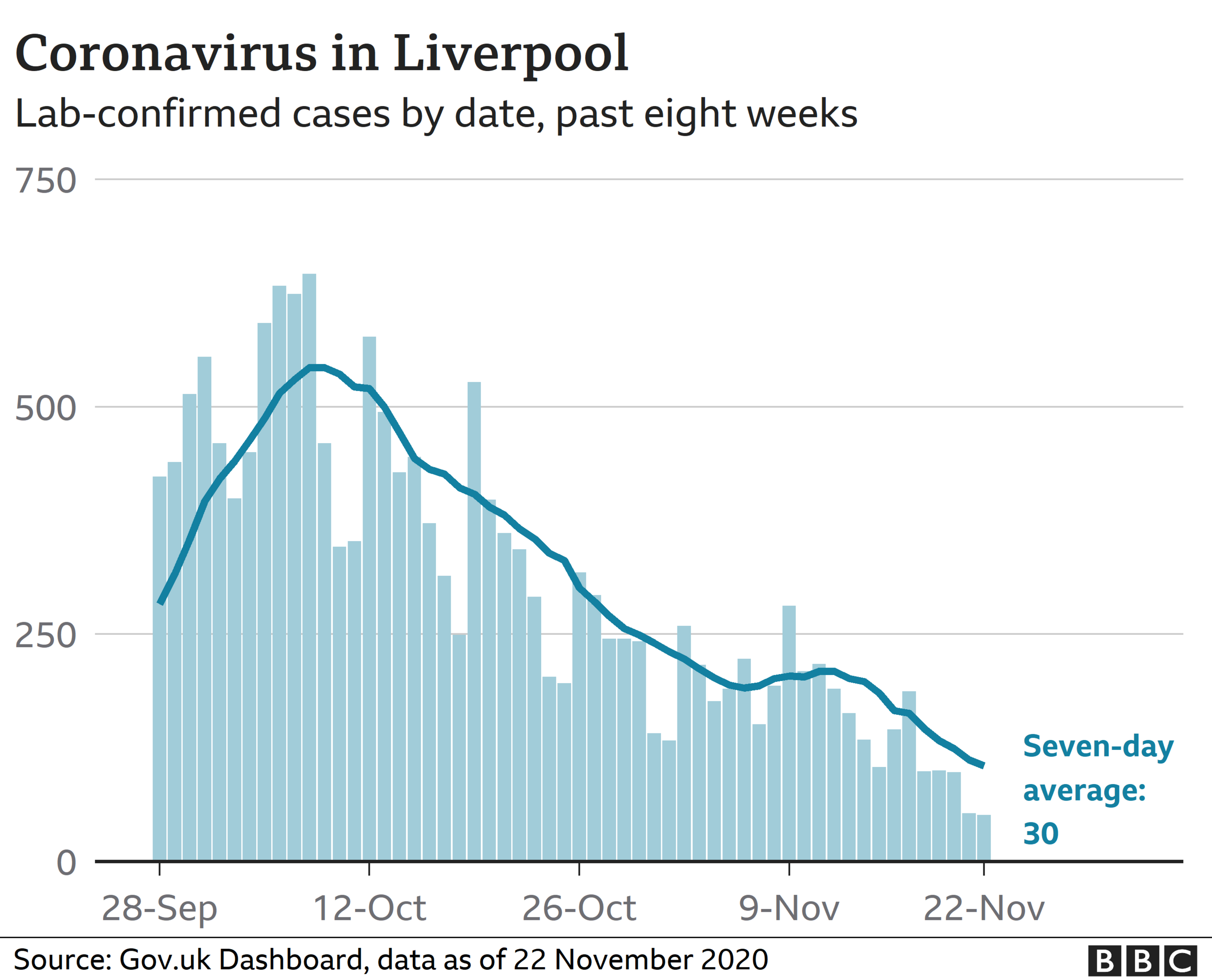

Despite recording the third highest coronavirus spike in Europe just six weeks ago, Liverpool's restrictions have been downgraded.

Boris Johnson described it as "a success story which we want other parts of the country to replicate", so how exactly did they do it?

On a clear night in late July, Liverpool lifted the Premier League trophy, the club's first top flight success in 30 years. The spring wave of Covid-19 cases was largely over and life was beginning to get back on track. But local health experts were concerned.

"I think it's fair to say that we were always worried in Liverpool," says Louise Kenny, executive pro-vice chancellor at the University of Liverpool's health and life sciences department.

"I think those of us who were well-sighted on the amount of community transmission were always worried that we would have a bad second wave because we never got down to the exceptionally low levels that were seen elsewhere in the country."

Liverpool's Jordan Henderson lifts the Premier League trophy

As schools reopened, pubs got busier and the prime minister encouraged workers back to the office, cases in Liverpool started to rise once more.

Before long, a slow trickle became a rapid spike, with 635 cases per 100,000 recorded in the city region on 12 October. Despite some very public warnings, Joe Anderson says he wasn't able to speak directly to the government until shortly before that peak.

Downing Street had been formulating a three-tier system and he was invited to join a video call with Mr Johnson's senior adviser Lord Lister and Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick.

Financial effects

During long, sometimes tense, meetings over three consecutive days, the three men and officials on either side thrashed out the details of a plan.

They all agreed that Liverpool should enter the highest tier, but arguments focused on a financial relief package.

On the third evening, an agreement had been all but reached. But with the finer points still to be signed off and Liverpool's MPs not yet officially in the loop, details of the negotiations leaked.

Liverpool Mayor Joe Anderson grabbed the mass testing pilot opportunity "with both hands"

"We found out from the news," says one Liverpool MP.

"The government didn't talk to local MPs at all, it was pretty disgraceful."

Like most of the UK, Liverpool was still reeling from the financial effects of the spring lockdown and some worried that further restrictions would only make the situation worse.

Intensive care

At the Micah Liverpool food bank, executive director Paul O'Brien says he and other volunteers noticed a change.

"You can see it sort of physically when people walk up to the food bank. I think once you've been doing these things for a couple of years, myself and the volunteers are able to say 'oh, they're coming to the food bank'.

"Then all of a sudden those people who you think are just walking past are coming in and you think 'oh, they're using the food bank as well'.

"These are people who've only just come out of work or not long come out of work, have used up all their savings and now they've been forced into a position where they've had to use a food bank."

Mr Anderson says he called for physical resources and the Army in a meeting with No 10

Several business owners phoned Mr Anderson in tears over the measures, but the mayor was determined that lives should come first.

That position became all too close to home when on 16 October, just two days after Liverpool officially entered tier three, the mayor's brother, Bill, passed away.

"Bill was in the intensive care unit in the Royal Liverpool Hospital," says Mr Anderson.

"He was taken in at 2 o'clock in the afternoon. At quarter to 10 that evening he lost the battle.

"I'm absolutely clear that if lockdown would have happened in September, then Bill I believe would be alive today, but so would many other thousands of people."

'Free rein'

For some time, the government had been considering piloting a system of mass testing. During that initial wrangling with Lord Lister, Mr Anderson sniffed an opportunity.

"I said to Ed Lister, it's not just about money, we need some physical resources, so what about using the armed forces to help us manage and do some of things around testing and his jaw dropped a little bit."

Several days later, Health Secretary Matt Hancock, who knew Mr Anderson from his days as Theresa May's culture secretary, called up the mayor of Liverpool to ask if he'd be interested in hosting the pilot.

The conversation didn't last long.

"I grabbed it with both hands," says the mayor, "because I knew it was going to help us."

Liverpool has a long history of public health interventions, including a period of mass testing for TB in 1959. That local expertise was soon drawn upon.

"We were offered the chance to work with the Department of Health and Social Care," says the University of Liverpool's Louise Kenny, "and our military colleagues who very kindly came to the city to provide logistics and support for the rollout."

Liverpudlians queue for a covid flow test

"But we've had a pretty free rein really in the ongoing design of how best to use that capacity for serial testing and what the university brings is the ability to analyse this pilot and provide that data to inform next steps, both locally and hopefully nationally," she adds.

'Not a lapdog'

Since mass testing began in early November, research has shown that take-up in the city's most deprived areas has been low and Paul O'Brien says many of the people he meets at the food bank have concerns about both testing and vaccines.

"Exactly what's happened with the testing seems to have happened with the vaccine and I do think it will be something that people get behind eventually, but we just need more information.

"There's so much, sort of, ambiguity about where it's going to be rolled out, when it's going to be rolled out, who are the target groups it's going to be rolled out to.

"There's just so many unanswered questions aren't there?"

Since mass testing began in Liverpool, the number of cases there has fallen rapidly.

After Thursday's announcement that Liverpool will be downgraded to tier two, Joe Anderson has pointed to the wider city's efforts.

Some in government have heaped praise on Liverpool's leaders, suggesting that the key factor was the speed with which they agreed to the original tier three restrictions in October, in contrast they say with areas like Greater Manchester.

But that's not a comparison that sits favourably with the mayor.

"I think it's outrageous to be frank. We're not a poodle, we're not a lapdog. I resent and reject any claims of compliance.

"I wish they would say it to my face, because I've got a pair of boxing gloves downstairs, I'd smack them right in the gob."

Listen to Jack's report from Liverpool on BBC Radio 4's Westminster Hour at 22:00 GMT on Sunday

- Published26 November 2020

- Published23 November 2020