Coronavirus vote: Why it feels like a government without a majority

- Published

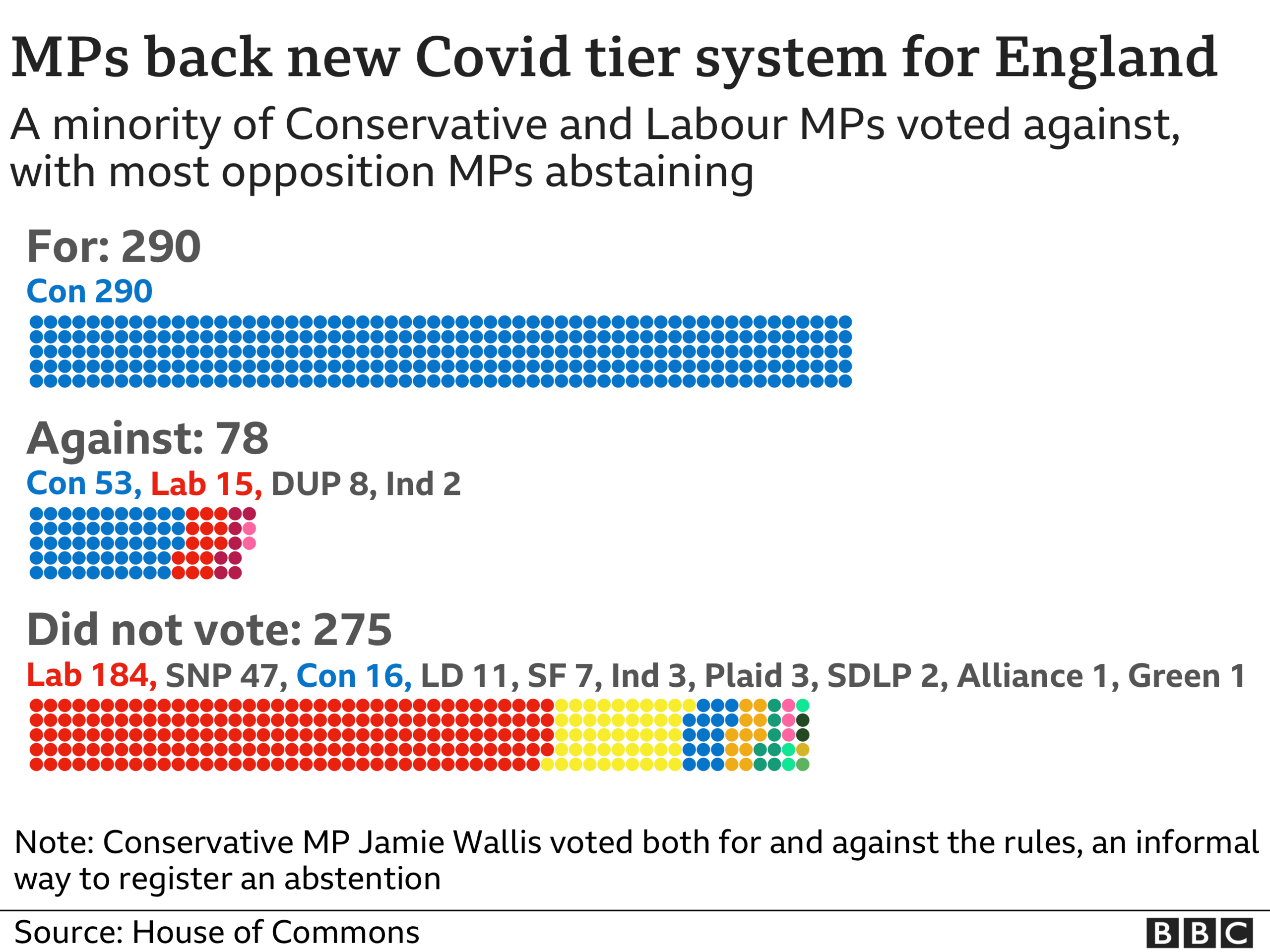

Boris Johnson faced a rebellion from 55 of his own MPs on Tuesday

Why does this feel like a government without a majority?

It's not even a year since Boris Johnson was carried to a thumping victory on the back of months of agonising parliamentary fiasco over Brexit and up against Jeremy Corbyn.

The majority was never in that much doubt, but the scale of the victory was something the Tories had only really dreamt of.

And it should, theoretically, have given Boris Johnson the kind of comfortable cushion in the Commons that no prime minister had had since the days of Tony Blair.

It seemed in Tory circles, for a while at least, that he was ruler of all that he surveyed.

That has hardly gone according to plan.

Despite the prime minister making appeals in person to MPs tonight, although Downing Street had moved over the last few days to meet some of their unhappy MPs demands by publishing documents, and promising more votes in the near future, 55 Tory MPs banded together to give the Boris Johnson his biggest Parliamentary kicking yet - even though he was said to be glowering at them as they tramped through the 'no' lobby (those who voted in person tonight at least).

With more abstaining, the message from the backbenches to the government's front row was clear - right now, Downing Street should not feel able to rely completely on their support.

Remember, the vote did actually pass.

The most important impact of the vote is, of course, in the real world, where from just after midnight, England will be carved up into three different tiers to try to manage coronavirus.

But this is a notable political moment too.

If the opposition parties had also voted against the government, the prime minister's plan - and his central mission right now in government - would have been sunk.

He'd have been defeated, the proposals kaput.

Why then does this feel like a government that is far less stable than the numbers would imply?

'Protest vote'

First off, and most straightforwardly, many MPs who didn't back the government tonight were doing what they feel they are sent to Westminster to do - to stand up for their specific areas, rather than just blindly back their tribe.

In particular, this meant MPs from areas where Covid infections are low, but regional restrictions are to be tight, protested by voting no - a practical, rather than a philosophical objection perhaps.

Second, there has been unease for many weeks in Tory circles about the government's overall approach to the restrictions - anxiety that the economic concerns aren't being given enough weight, and that patients who don't have Covid are losing out simply too much.

On both of those fronts, of course, the coronavirus crisis is unprecedented as an administrative nightmare for every government around the world.

It hasn't happened before, so no one can be sure of the right thing to do.

Beyond that duet of reasons, however, there are other political factors at play.

Watch the moment it was revealed that MPs approved the new tiered system

Let's start with - and bear with me - Brexit.

Covid and Brexit are not directly linked. But no issue on the political planet is an island.

The government is in the final throes (honest) of the Brexit negotiation process, just as ministers are moving England to a new set of tiers.

Just as backbench hackles begin to rise about any concessions the prime minster may be prepared to make, along comes a vote where anxiety can be expressed - an opportune moment, perhaps, to remind Downing Street that those MPs who developed rebelling into an art form will not be willing to suck up any old deal.

One cabinet minister suggested there was "a lot of nervousness around the Brexit messaging about a possible deal [and] Covid is a good outlet", saying there was a "remarkable" similarity between the cast list of Covid sceptics and Eurosceptics.

Another suggested the objectors were the same old "awkward squad", who enjoy causing trouble.

There may, or may not, be a deal with the EU that Parliament has to approve in the next couple of weeks (at breakneck speed if things carry on at this rate with the negotiations) and it is likely at least some of those who voted against the government tonight were motivated, in part, to give No 10 a reminder they can't be taken for granted.

The objections went beyond that group, however, including some prominent former Remainers and ministers, and even some of the new 2019 intake, who ought not to carry the Brexit scars.

'Strong signal'

The second political concern some MPs were trying to express was a frustration at the government's overall competence and direction.

No one in Westminster, Edinburgh, Cardiff or Belfast could claim that handling coronavirus is easy.

But one of the rebels - even a Boris Johnson fan - told me the vote was a "strong signal that we cannot carry on like this", adding: "The government must stop these lurches and engage MPs more about all aspects."

Another senior Tory, a former minister, said "the mood is toxic", suggesting relations between the backbenches and Downing Street are getting worse, not better - even though this is one of the first big set pieces since the departure of Dominic Cummings that was meant to herald a "reset".

They added: "The tom toms are beating. We said we would take back control, but it feels like the government has lost control."

There are even questions on the inside about what it's trying to achieve, with one member of the government telling me tonight: "The basic problem is that there is not a governing philosophy for this government other than Brexit.

"Without that to hold the party together, and coming into its 10th year in office, the parliamentary party is inevitably restless and grumpy."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson: "This is not a return to normality"

Worrying, perhaps, for ministers tonight too, while the PM was involved in significant lobbying of wannabe rebels to try to keep the defeat to a minimum, his Tory opponents were not trying to gather support as aggressively as they might have done.

I'm told by sources involved they did not work as hard as they could have done to ratchet up their numbers.

Rather than inflicting a heavier defeat, they wanted to make it clear that more of their colleagues would rebel next time if the policy doesn't change.

'More stable?'

One defeat, of course, does not doom a policy, and it certainly doesn't end the hopes of a party.

One of the easiest things you hear uttered in politics is "we can't go on like this", and then somehow, it almost always does.

And a cabinet minister predicted today that after the worst of Covid, with vaccines on the way and the conclusion of the Brexit process (before you scream, of course there will be issues between the UK and the EU for ever, but this bit will soon be done at least), the government would be able to get on with passing laws that Tory MPs and voters wanted.

Their hope then is the 2019 majority will yet lead to a politics that is more stable, perhaps more boring (shock!), and certainly much more comfortable for the prime minister.

Politics has, however, in the last few years developed a reliable habit of surprise.