Covid: The inside story of the government's battle against the virus

- Published

At the beginning of March 2020, I asked a senior member of the government: "Do you feel worried?" They replied: "Personally? No." But just weeks later, Downing Street was scrambling to manage the biggest crisis since World War Two.

Since then, monumental decisions have had to be taken. And there have been many accusations of failings - the desperate shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), Covid ripping through unprepared care homes, hundreds of billions borrowed and spent to keep the economy going, to name a few.

I have asked 20 of the most senior politicians, officials and former officials, who either witnessed or were involved in the big decisions, to pick five pivotal moments from the past 12 months.

What they say tells us so much about what really happened, what our leaders were thinking, and, strikingly, how little they knew. The contributors are not being named, so they could speak freely.

The virus on our doorstep

On 31 January, it was reported that coronavirus had arrived in the UK, as two people were admitted to hospital. Meanwhile, more than 80 Britons evacuated from China were quarantined at a facility in the north-west of England. But for the government, Brexit had sucked up all the political energy - it was the day the country officially left the EU.

The prime minister and his team were exhausted but elated. It felt like Boris Johnson had "just really started to take flight", one member of the team tells me.

Ministers and officials had already been meeting to discuss the virus in China - but it felt thousands of miles away. There was a "lack of concern and energy," one source tells me. "The general view was it is just hysteria. It was just like a flu."

The prime minister was even heard to say: "The best thing would be to ignore it." And he repeatedly warned, several sources tell me, that an overreaction could do more harm than good.

A small group in Downing Street had started daily meetings, after, according to one of those who attended, "it became clear that there was no proper, 'Emergency break-the-glass' plan."

But for many of those I've spoken to, the game-changer was at the end of February, when the virus took hold in northern Italy - it was closer to home, and England's chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, had, one minister told me, warned that if it got out of China, it would become global, and be on its way to the UK.

"The biggest moment for me was when I saw those pictures of northern Italy," one senior minister says. "I thought that will be us if we don't move."

Reports of the chaos there catapulted the virus, one senior minister says, "from not on the radar, to people on the floor of hospitals in Lombardy." They say that was the moment "we knew that it was inevitable".

Ministers and officials became locked in arguments over how to respond. The prime minister and many cabinet ministers were reluctant to consider anything as draconian as a lockdown. To many people, the very idea would have seemed fanciful.

Even stopping shaking hands seemed a step too far for the prime minister.

Before the first major coronavirus briefing on 3 March, he had, I am told, been prepared by aides to say, if asked by journalists, people should stop shaking hands with each other - as per government scientific advice.

But he said the exact opposite. "I've shaken hands with everybody," he said, about visiting a hospital with Covid patients.

And it was not just a slip, one of those present at the briefing says. It demonstrated "the whole conflict for him - and his lack of understanding of the severity of what was coming".

A Downing Street spokesperson told the BBC: "The prime minister was very clear at the time he was taking a number of precautionary steps, including frequently washing his hands. Once the social distancing advice changed, the prime minister's approach changed."

By this point, Mr Johnson was attending emergency committee Cobra meetings with officials and leaders from Holyrood, Belfast and Cardiff - although he had missed the first few.

But one senior politician who attended at the same time says: "The early meetings with the prime minister were dreadful." And inside Downing Street, senior staff's concerns about the government's ability to cope grew.

There were huge logistical considerations about equipment, facilities and how fast the disease might move in the UK, and questions about how effective the actions taken in China to suppress the virus would be here. It was not well understood, for example, that people without symptoms could still pass it on, nor that Britons returning from half-term holidays in northern Europe were bringing the virus back home in large numbers.

"There was a genuine argument in government, which everyone has subsequently denied," one senior figure tells me, about whether there should be a hard lockdown or a plan to protect only the most vulnerable, and even encourage what was described to me at that time as "some degree of herd immunity".

There was even talk of "chicken pox parties", where healthy people might be encouraged to gather to spread the disease. And while that was not considered a policy proposal, real consideration was given to whether suppressing Covid entirely could be counter productive.

On 3 March, when the prime minister set out the government's plan, the focus was on detecting early cases and preventing the spread.

But on 12 March, with journalists crammed into the state dining room at No 10, he told the public that the country was facing its worst health crisis in a generation. Anyone with symptoms was told to stay at home for a week.

Advisers seemed confident it was not yet time to close schools or stop large crowds gathering. And the government's scientists felt they had time to slow everything down - the peak was not expected for another 10-14 weeks.

That same week, though, nervousness was rising among others in government that the virus was outpacing everyone's expectations, and the plans in place to smooth out the outbreak would not work.

One source tells me it felt like the "government machine was breaking in our hands", things were "imploding", and within 48 hours the approach outlined on the 12th would feel out of date.

There has been no shortage of controversy over whether the government was too slow to close the doors on 23 March - but many of the conversations I have had, pinpoint the moment it became urgent in No 10.

On 13 March, the government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) committee concluded the virus was spreading faster than thought.

But it was Downing Street "modellers in the building", according to one current official, who pored again over the numbers, and realised the timetable that had only just been announced was likely to result in disaster.

The next morning, a small group of key staff got together. Simple graphs were drawn on a whiteboard and the prime minister was confronted with the stark prediction that the plan he had just announced would result in the NHS collapsing under the sheer number of cases.

Several of those present tell me that was the moment Mr Johnson realised the urgency - that the official assumptions about the speed of the spread of this new disease had been wrong.

To prevent the NHS "falling over", he was warned, the government would have to impose measures as infections rose. And while they could be relaxed as cases fell, this pattern might recur across "multiple waves for 18 months".

Several sources recall vividly the "snake like graph" they were shown that day.

Then, one official says, everything started to move at "lightning speed". And behind closed doors - before the terrifying projections of Imperial College became public, a couple of days later - plans were accelerated.

On 16 March, the public were told to stop all unnecessary social contact and to work at home if possible.

New cabinet committees were formed. And the machine moved into a different phase, with the prime minister and the "quad" - Matt Hancock, Michael Gove, Dominic Raab and Rishi Sunak - the new decision-making form. It was, I am told, "high tension - [with] a lot of testosterone in the room".

For many inside government, the pace of change that week was staggering - but others remain frustrated the government machine, in their view, had failed to move quickly enough.

There was tension between those who wanted to ensure systems were as ready as they could be first, and others who argued vociferously that moving fast against the virus was more important than anything else.

But those I spoke to now agree on one thing - how much they did not know about the disease.

"You can kick yourself about the things that you wish you knew," one minister says, "but we just didn't have anything in place."

Another cabinet minister says: "It's easy to say we should have locked down longer, gone harder, but there are more complex debates about where the national interests really lie."

And it was all so strange.

One minister who made some of the public announcements when lockdown came says: "I remember when I wrote it into the script, I just couldn't believe that I was saying this."

And one official, struck by how huge it all felt, says he googled: "Did they shut the schools during the War?"

Another, meanwhile, admits, "We were more blind than we told the public," and suggests that is still the case one year on.

Boris Johnson out of action

On 18 March, we reported that a small number of members of staff in No 10 had fallen ill. One insider says: "People were dropping like flies."

The prime minister, however, was acting as though he was impervious to the risk. He had developed a habit of banging his own chest, telling staff he was "strong as a bull". Soon, though, this chest-banging turned into "extreme coughing fits". Tests, in short supply everywhere, were requested for him from 25 March. And two days later, he tested positive.

He switched to the chancellor's bigger suite of offices so that he could keep working, screened off from the rest of the building. Insiders recall how much he hated this and, in a second spell of isolation in the autumn, chairs had to be placed across the door "like a puppy gate", so he could still communicate with the tiny number of staff allowed into the same part of the building.

Then, at the end of March, the prime minister became increasingly ill - each video call he made to reassure the public required more takes.

On 6 April, he agreed to go to St Thomas' Hospital and, struggling for breath on a phone call, I have been told, confirmed he wanted Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab to stand in for him.

Initially, Downing Street tried to give the impression that all was well. Journalists were even told that Mr Johnson was working on his red boxes. That message has been put down to a mix up, and we now know this was far from the truth.

The moment of genuine crisis came when he was moved into intensive care. No-one knew if the prime minister would make it through the night - or what the plan was if he did not.

By this point, with so many in No 10 and in government already sick, there were, I have been told, about "half a dozen people running things".

Fears that he might need to be intubated were shared by a tiny group inside Number 10. They discussed the possibility that ministers would have to gather in the cabinet room, with the doors closed, until they chose a successor - but there was no fixed protocol, and no conclusion was reached. The Tory Party, I have been told, even started to consider how to transfer the leadership without a contest, fearing that such a competition could be seen as "venal" after the prime minister's death.

Then cabinet ministers were summoned urgently for a conference call. "All of a sudden we were asked to join this call - not knowing if he was alive," one tells me. Then No 10 prepared to make the news public.

The Downing Street voice on the other end of the phone cracked with fear as I was asked to get to the Foreign Office as soon possible with a camera to talk to Mr Raab, who was being sent out to try to reassure the country. We reported the news that Mr Johnson was in intensive care from the back of a taxi.

A former official tells me: "We thought we really could lose him - we had to plan for a full transition." That night was "long and shocking", one source says.

The Barnard Castle misadventure

By the end of May, the number of coronavirus cases was falling, the prime minister was back at work full time, and the public had surprised the government by overwhelmingly sticking to the rules.

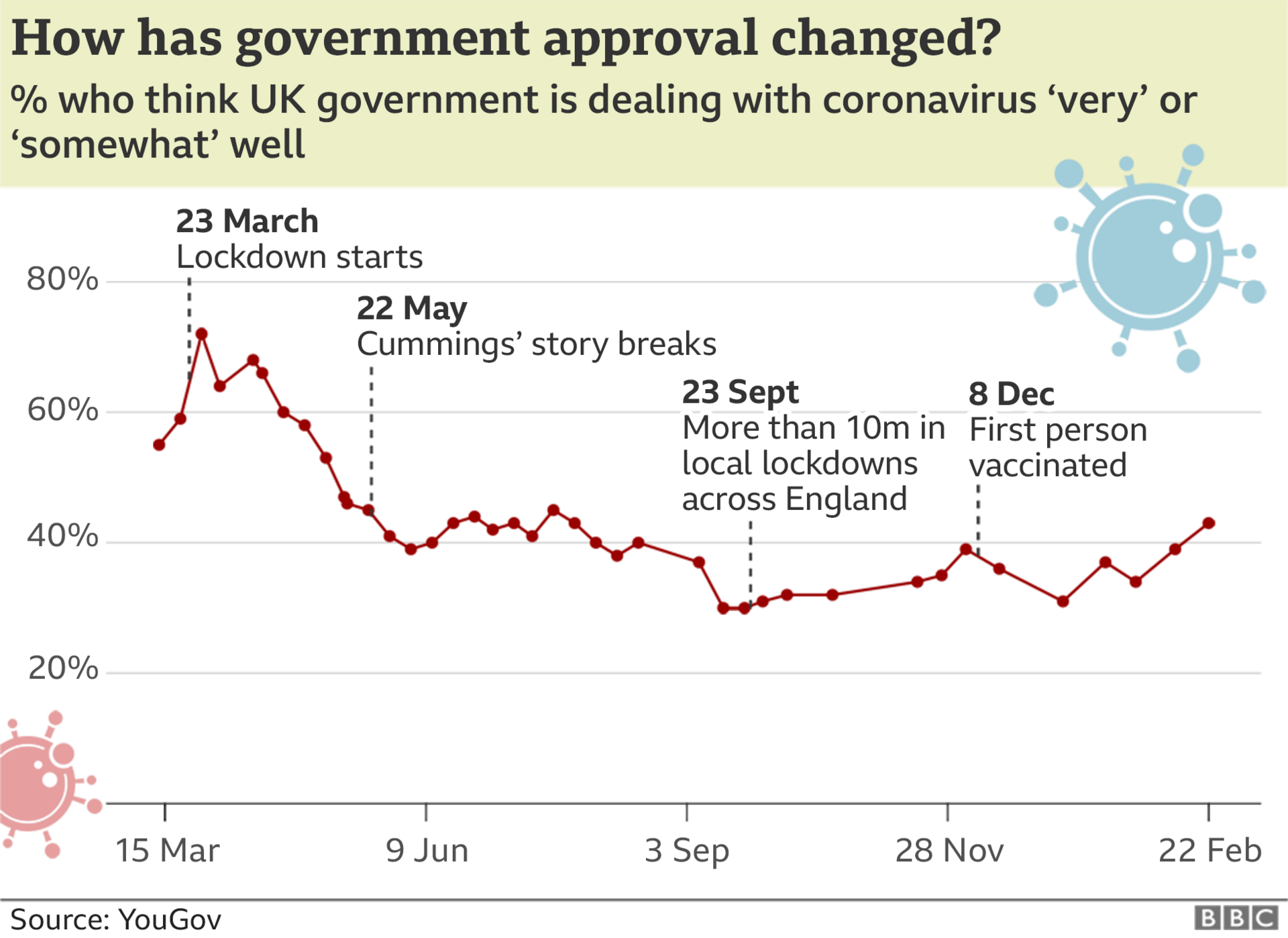

Furthermore, despite some embarrassing and prominent lockdown breaches - in April, for example, Scotland's chief medical officer, Catherine Calderwood, had to quit over her visits to her holiday home - there had been what one senior minister describes as "tremendous goodwill".

But then came the Mirror and the Guardian's scoop - in March, the prime minister's chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, had travelled hundreds of miles to County Durham, after his wife fell ill with Covid. He, too, succumbed to the virus and his stay on his family's farm to recover, before returning to London, had been kept secret - apart from among a tiny number of Downing Street staff.

And Mr Cummings was determined not to quit. After considering sacking him, the prime minister stuck by him - but first, there was what has been described to me as tense "mediation between a couple deciding whether to divorce".

Before making that decision, he had summoned Mr Cummings to go through his version of events. Together, they planned for him to give this version publicly - despite others' protestations. The result was the surreal press conference in the Downing Street rose garden.

Many of those I have talked to describe this episode as a terrible turning-point.

"Even for us, this is mad," a member of the Downing Street team tells me.

Senior ministers say: "The handling was a fiasco". "It was ridiculous", and, at a time of national emergency, "broke the political consensus".

Perhaps, after two months of lockdown, the public was ready to be angry with someone.

MPs' inboxes were swamped with irate emails - mine too. "The early pandemic washed away all the bitterness of Brexit," one senior minister tells me. "That all came flooding back, all that bile, all that pent up frustration."

Some ministers tweeted their support for Mr Cummings. One of those who refused says: "He should have resigned straight away. You lead by example. I was busy chopping logs with my chainsaw to get the frustration out."

Some polling suggests the Barnard Castle episode really did dent the public's trust in the government. "It gave people who wanted to break the rules an excuse," one source says.

But inside government, there was a belief that an extraordinary period of unity had already started to fade, and the public had started to tire of the rules once the government had moved towards its plans to lift them.

There is no question, though, the whole misadventure made the politics of the pandemic more scratchy and less consensual.

Mr Cummings was not the only one to be caught up. In June, Northern Ireland's Deputy First Minister, Michelle O'Neill, provoked anger by attending a huge Republican funeral.

But it was after Barnard Castle that it felt like the mood in the country had changed.

"People wanted to portray the PM as a clown," one minister tells me, "or not up to the level of events."

Summer optimism, missed September

Britain in the summer did not feel like a country still gripped by a pandemic.

"There was loads of over optimistic messaging," one politician says.

For example, the time when a Labour MP asked for advice at the end of June for his constituency, which was home to a popular beach and he was worried about huge numbers heading for the sea. "Show some guts," the prime minister told him.

In July, a grinning chancellor delivered plates of Japanese curry to unsuspecting customers at a London restaurant, to promote his "eat out to help out" scheme. Then the prime minister started to encourage people back to the office.

But behind closed doors, there were significant doubts about the wisdom of this new mood. "We knew there was going to be a second wave," one cabinet minister tells me, "and there was a row about whether people should work from home or not - it was totally ridiculous."

The summer optimism and opening was "the biggest mistake - a rush of blood to the head", another senior figure says. "The PM has to carry the can".

The prime minister believed that another lockdown would be a disaster and wanted to avoid it at all costs - but for many of those involved in making the decisions, his hostility to tightening the rules again was frustrating, dangerous and political.

"The policy objective in the summer and the autumn was - do the minimum possible," one tells me.

But by the end of August, with Britons packing beaches, the warnings of what might come were already flickering in Number 10.

Some days, sources suggest, the prime minister would express concern about the virus coming back. Others, he would be in "let-it-rip mode". And senior officials expressed deep concern about what seemed to be changes of heart on a daily basis.

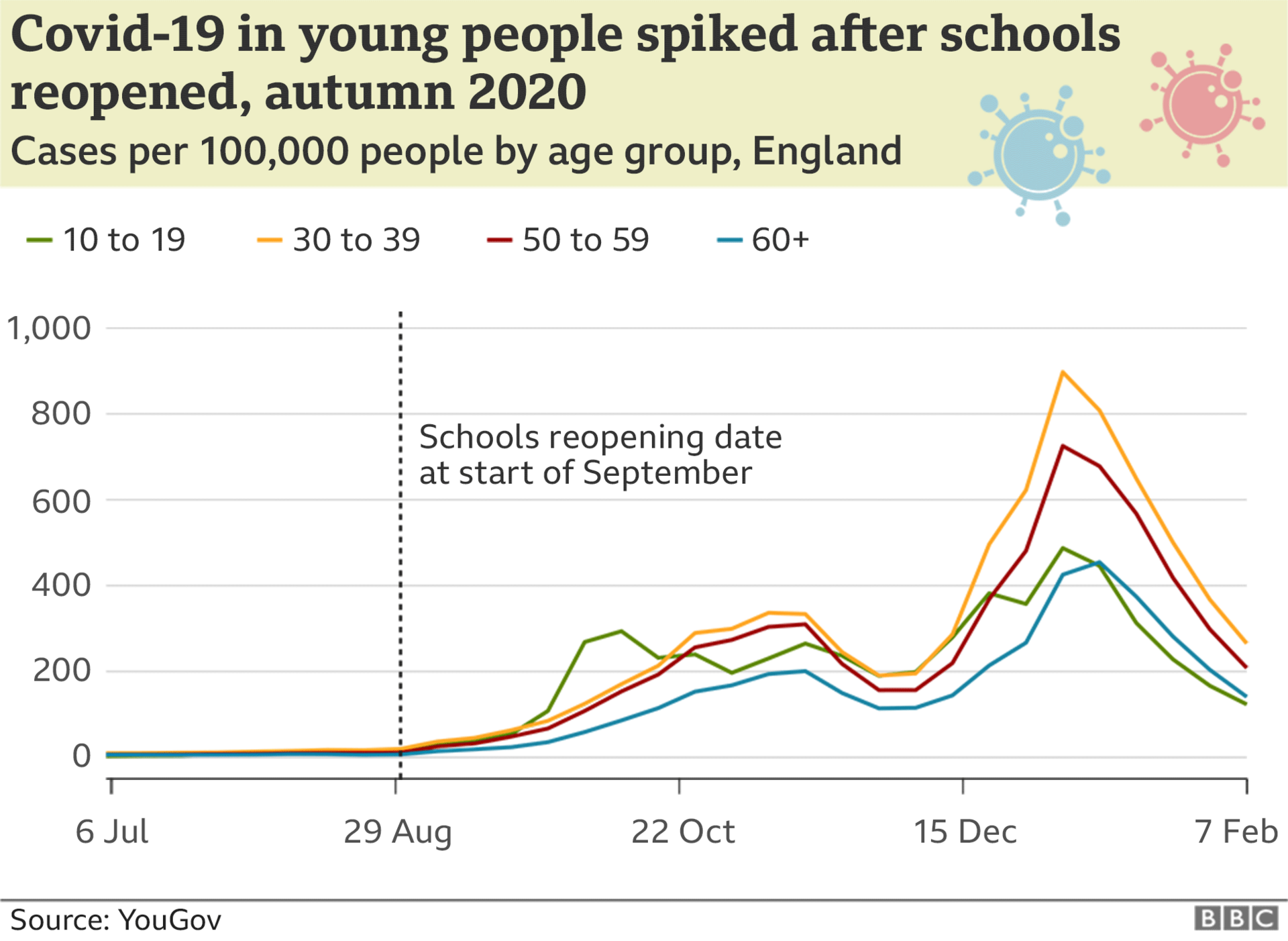

The disease would not be contained by indecision, and by the start of September, with schools and universities having returned, "you could clearly see a steady increase," a senior figure says.

The testing system had not been able to keep pace with demand, and too few people were willing to, or could afford, to self-isolate if they tested positive. "The idea that you could liberalise in the summer was based on the idea that you could whackamole with test and trace," the source says. "But if you didn't whack the right moles then it doesn't work."

By the middle of September, "the data was already screaming out", one insider says. On the 17th, I was told by one source: "If you do nothing now, by the end of October you will get something worse than the first wave."

The possibility of a short "circuit breaker" lockdown was already being discussed in Downing Street that week. Prof Whitty, the UK's chief scientific adviser Sir Patrick Vallance, and Mr Cummings and others were arguing hard for action to be taken - but the prime minister was unpersuaded.

Others wanted to push again - one current official recalls a "concerted effort" - and on Sunday 20th, the No 10 team gathered a range of scientists. But the prime minister remained reluctant.

Another current official describes his attitude as, "if there is a way not to act, why do it?".

Over the next 36 hours, I have been told, a small group inside Downing Street repeatedly tried to change Mr Johnson's mind - but by then, he was operating in a very different atmosphere.

"A swampiness had risen because of ideological pressure on this government at every turn to do less - and to do it more slowly," a senior figure says. And it is understood Mr Johnson had privately assured groups of MPs there would be no more restrictions.

The Treasury was pointing out the damage any further restrictions would do to the economy, many of the traditional Tory-backing newspapers were hungry for restrictions to be relaxed, the party was restless, and I remember cabinet ministers who had hardly any cases of the virus in their constituencies at that point, suggesting they saw no evidence for further action.

So when Mr Johnson made changes to the coronavirus restrictions on 22 September, they were tweaks, rather than a real tightening up. I remember talking to Tory backbenchers that day who felt they had won.

The importance of the missed September moment is cited by many senior figures - and some now concede it was a mistake.

"We strained at the leash to get things going," one cabinet minister admits. "I was aggressively for that - but I have learned that it is better to go slow."

Another senior minister, one of those who pushed for more radical action at the time, now says: "We should have locked down more severely, earlier in the autumn - the whole point was, the earlier you act the more you buy yourself time for a strategy that can get out."

You can still hear the frustration in the voices of those who lost the argument.

"The PM was saying the Tory Party won't swallow it," one tells me. "Everyone else felt, we know we are going to have to do a lockdown."

And there is no question that the tier system that was introduced over the autumn, which portioned England into different levels of restrictions, was soon tied up in confusion and regional spats.

"It was completely unintelligible to any normal human being," one senior official says. "It was too slow, and too Byzantine, and that resulted in more cases."

Another says now: "We ended up tying ourselves into ever tighter knots," as the system became more and more particular to each part of the country.

It is impossible to know what would have happened if the brakes had been slammed on in September - but some ministers pin the terrible scale of the second wave, at least in part, on the apparent reluctance to act.

The circuit-breaker that was imposed later in Wales did not make the problem go away, however. Case numbers weren't the only concern - the economy had been shuttered, and shattered. Political demands had changed.

In defence of Mr Johnson, one senior minister says: "He's not to blame if he was trying to reflect the aspiration for the country back in the summer". Another tells me the plans, and the billions spent on "test-and-trace and tiering meant it was reasonable to do the unlock".

They reject the idea that a circuit breaker was the obvious option - "There wasn't a slam dunk recommendation."

Regarding the potential introduction of national restrictions in September, Downing Street referred us back to comments made by the prime minister to parliament in early November.

"No-one wants to impose measures unless absolutely essential," Mr Johnson told the Commons. "So it made sense to focus initially on the areas where the disease was surging and not to shut businesses, pubs and restaurants in parts of the country where incidence was low."

But while there is no question mistakes were made in the first phase of the pandemic, when so much about the virus was a mystery, those involved in the decisions are already less forgiving of their own mistakes the second time around.

The big vaccine gamble

"A miracle," is how one minister describes the vaccine gamble to me. A government so often lambasted by critics for busting convention did it again - but this time, so far, with a stunning outcome.

Vaccines had been discussed in January, as the government machine began to contemplate, slowly, what might be ahead. Early on the chancellor, holding the cheque book, indicated a willingness to spend at speed, without asking for guarantees.

No 10 decided to "chuck everything at it", at a meeting in April. With Sir Patrick's crucial experience and deputy chief medical officer for England Prof Jonathan Van-Tam's emphasis on the practicalities of delivering the vaccine, politicians were persuaded to take what was then a huge risk.

There was an early decision to "pay high, pay early, and ensure it works," one senior official tells me.

And it seems their decision was informed by everything that had gone wrong with trying to secure PPE - the collapse of the NHS's normal procurement process, which is controlled by the Department of Health.

The UK decided early not to participate in the EU's joint plan to buy vaccines. While publicly this decision may have been politically controversial, behind closed doors it was "easy" and "straightforward", ministers and officials say. "No-one wanted any of the Brexit baggage anywhere near it." And, more importantly, the EU had made it clear any participating country would be unable to make its own deals with manufacturers the EU had an agreement with - or control its own supply.

The vaccines team had warned ministers at the start of May that nothing was certain - and developing a vaccine as quickly as the prime minister, who "wanted it yesterday", required would be an uphill struggle. But, as one minister says, it was "the one thing we would wish that we had done in a year's time".

Another, a senior minister, says: "The PM strategically saw immediately that the combination of testing, drugs and vaccine was the way out." And when it came to vaccines, the UK was ready to take an expensive gamble.

The Treasury was spending speculatively in ways it had not since the War - and vaccine spending has already reached nearly £13.5bn. "Imagine if it hadn't come off and we had spent all of that taxpayers' money," one senior official says to me.

There was intense secrecy, throughout, with the various vaccines given secret code names to ensure commercial confidentiality. All were named after submarines - the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine "Ambush", I can now reveal, and the Oxford-AstraZeneca "Triumph".

After 12 months of grappling with endless calculations about balancing risks to life, wider health and how the country makes a living, decision-makers are exhausted. They have to accept it is perfectly possible to be wrong, one senior minister tells me. And those who made the decisions are all too aware mistakes they made in these past 12 months may have had such a terrible cost.