Can Priti Patel's asylum plan work?

- Published

Many people smugglers send asylum seekers across the Channel in dangerously small boats

There is a warning from history for Home Secretary Priti Patel - and it comes from what happened to the Labour Party when it too faced what it was describing as a crisis in the asylum system.

Back in 2003, Tony Blair - the then Labour Prime Minister - was under such sustained pressure over asylum seekers entering the country that he made a PR-savvy pledge to halve the number entering Britain before the year was out.

He hit the target, external - but that year also poisoned the public mood against the government.

No matter what the government did or said, many people concluded ministers had no control of immigration.

All these years on, Home Secretary Priti Patel is telling us that the system is still broken because the numbers are unsustainable.

What are the asylum numbers?

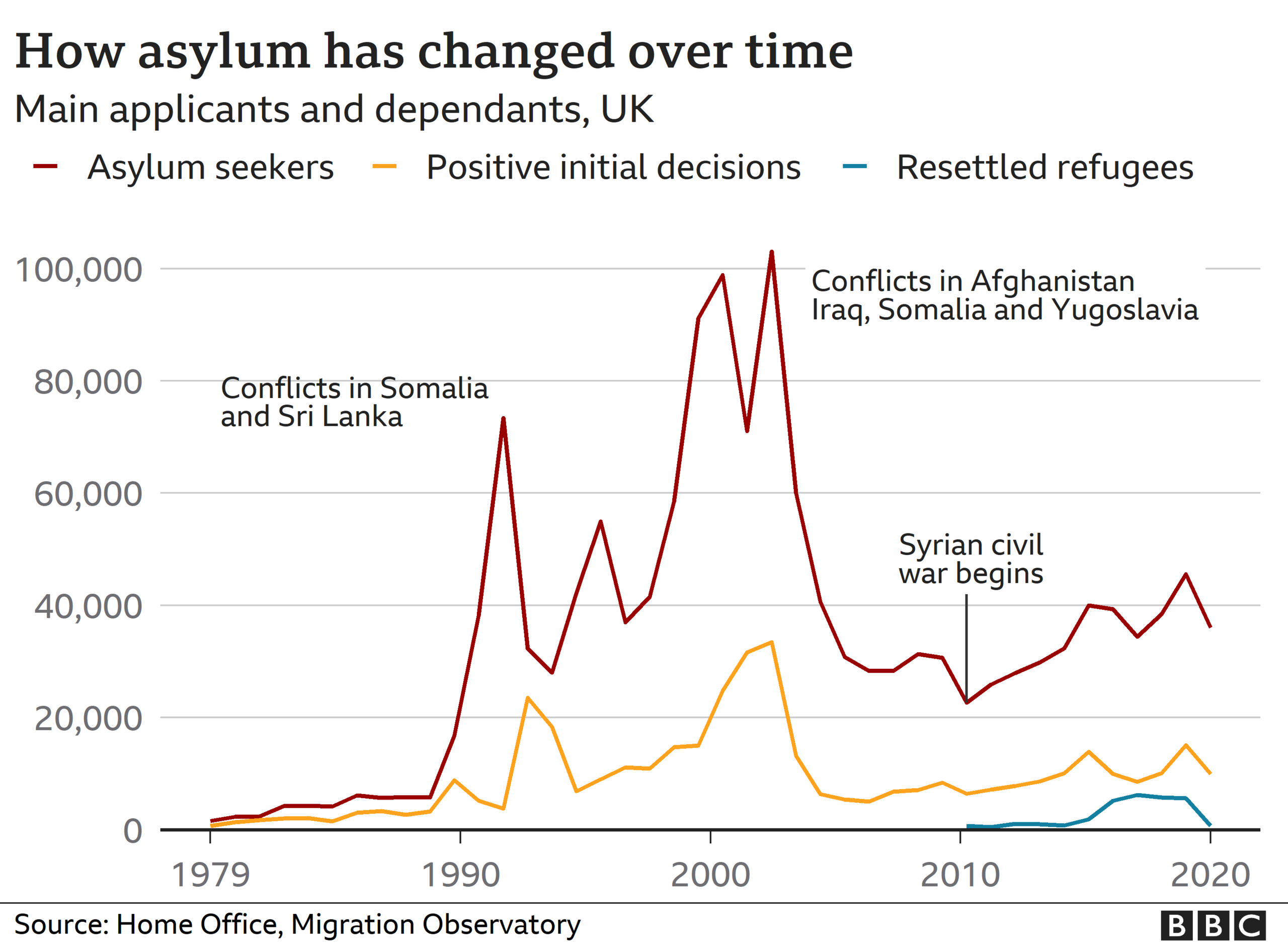

In the context of 20 years of immigration crises, the total number of asylum seekers arriving in the UK is actually very low.

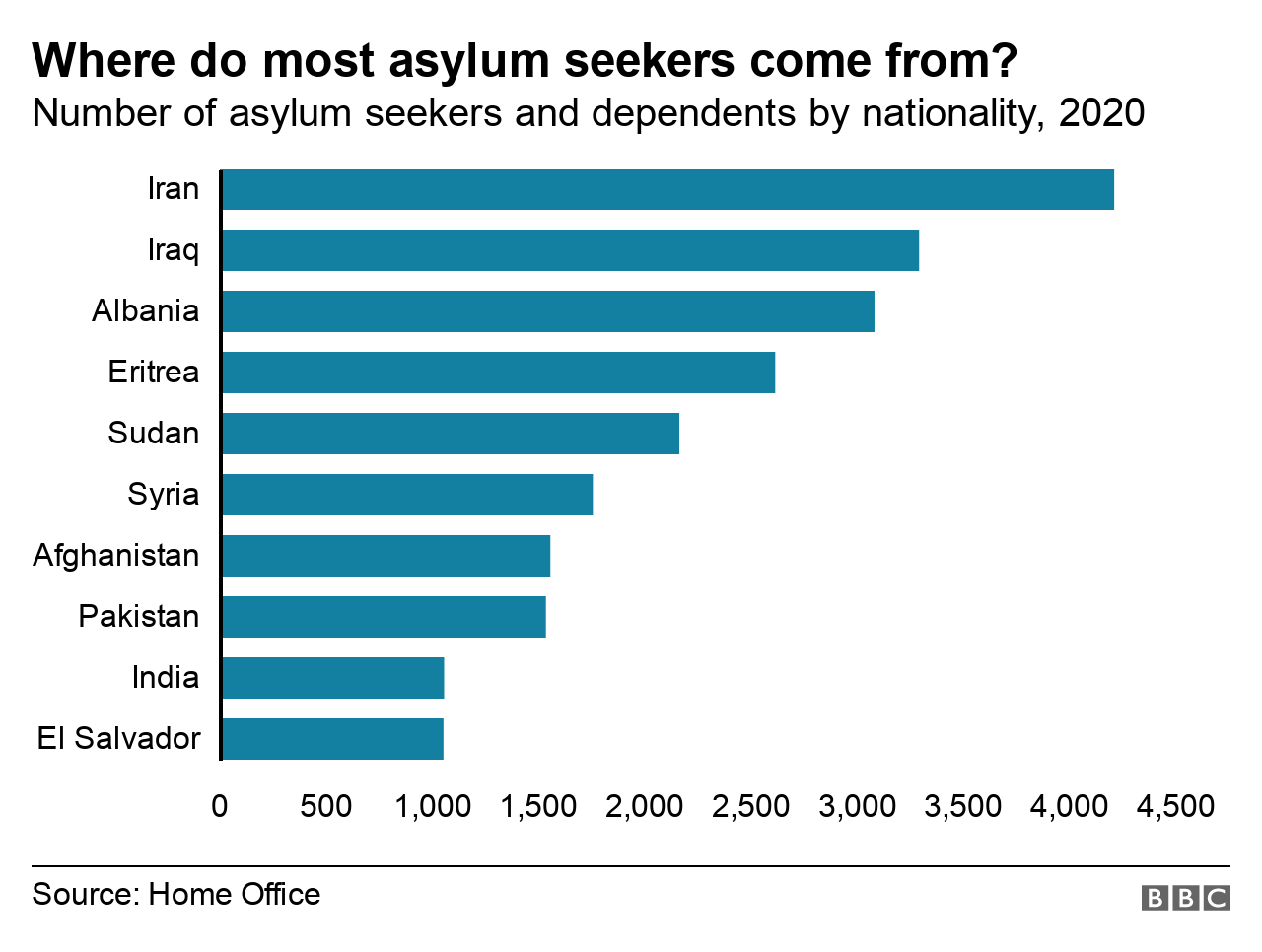

Last year, almost 30,000 people sought asylum here - and more than 8,000 of them crossed the English Channel in small boats, with the help of people smugglers.

That's a third of the all-time record set in 2002 when the issue gripped the nation. And the UK's figures are nowhere near Germany's, which admitted more than one million in just a year during the Syria crisis.

To put all of this into context, earlier this week there were 183 cross-Channel migrants into Kent on one day. To reach the levels seen in the UK at the start of the century, dinghies would have to bring 300 a day, every day, for a year.

While the numbers of applicants have indeed recently begun to rise again, so has the backlog of unresolved cases.

In 2010, almost 12,000 asylum seekers were waiting to hear if they could stay in the UK. Just before the pandemic hit, that number had reached almost 44,000.

Cases are taking longer to resolve and that, in turn, makes the system more expensive, as the Home Office has to house and feed people who are not allowed to work while they wait for a decision on their futures.

And so these statistics lead critics to say that the real problem remains fundamental mismanagement of asylum over decades.

Can Priti Patel's plan make a difference?

Home Secretary Priti Patel says the new rules are based on the principle of fairness

Let's take the core proposal to treat some asylum seekers differently to break the power of criminal gangs.

Anyone coming via proposed new official routes, such as the recent Syrian resettlement scheme taking people from camps, would be fast-tracked into a new and permanent life in the UK.

Just putting to one side the fact that we don't know what these officials routes are, anyone who doesn't use them may be relying on people smugglers.

The UK will restrict that group of people's rights to live a normal life and try to send them back to other safe countries they have passed through along the way.

Those it can't eject will never get permanent residence and will face repeated attempts to remove them in the years that follow.

The aim is to undercut the awful criminal economy of smugglers who profit from misery as they pack people onto boats.

Is that legally workable?

Many legal experts predict the plan would breach the international law that the UK helped devise - that states we should treat all asylum seekers equally and fairly.

But officials think that's not quite the point and there is room to create sanctions to break the link with criminal gangs.

Under Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, external, countries can't penalise refugees for illegally entering a nation, providing they come "directly" to its shores, or have a good explanation for how they have turned up via some more complicated route.

But while an asylum seeker is not obliged to seek sanctuary in the first safe country they reach, nor do they have an unfettered right to shop around.

The Home Office seems confident that provides the legal room for it to take steps against asylum seekers who have paid smugglers, in the hope that it will deter others from doing the same.

Are there other questions with the plan?

Just supposing all of this becomes law, there is an elephant trumpeting away in the Home Office's shiny glass atrium: where is the UK actually going to send anyone whom it wants to get rid of?

The number of people being removed from the UK - be they failed asylum seekers or, separately, foreign national criminals, has been falling over a decade.

And the UK has not been able to send a single failed asylum seeker to its immediate neighbours since the end of Brexit, when it left the EU-wide system governing such transfers.

There is no new legal agreement in place - and there is no way that the UK can force France, Italy, Greece or wherever else to receive people without permission.

The Home Office hopes to strike new deals - but until it does so there is the possibility, say some experts, that the plans will just make matters worse.

If attempts to discourage people from using smugglers fail, people will still be turning up, but now without the right to settle permanently and put down roots.

Denied benefits or the right to work under the planned restrictions, they could end up destitute.

And if they can't be sent anywhere else, they may remain on the streets, in limbo.

Just like Tony Blair's government, the challenge for this Home Secretary is to have enough time to prove that the system she says is broken is on its way to being mended.

- Published13 December 2023

- Published24 March 2021