Which prime minister didn’t enjoy life at No 10?

- Published

This weekend marks the 300th anniversary of the role of prime minister.

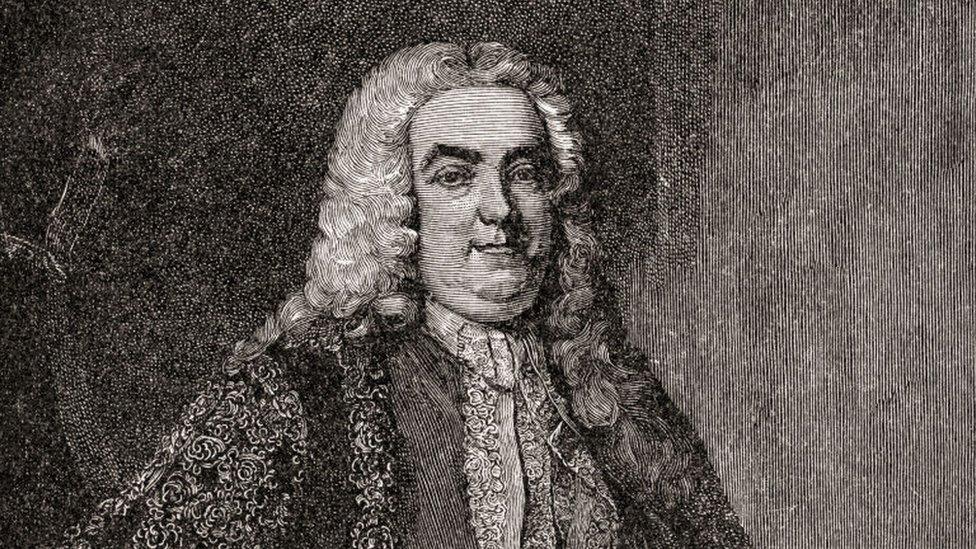

On 3 April 1721, Sir Robert Walpole became Britain's first PM, and since then a cast of 54 occupants have tried to change the course of the country, though only a small number have succeeded.

Most prime ministers leave office in unhappy circumstances, having been thrown out by the electorate, pushed out by their parties or succumbing to ill health.

"I don't think I did enjoy the job," Tony Blair told us. "Because the responsibility is so huge.

"Every day you're making decisions and every day you're under massive scrutiny as is your family. The paradox is that you start at your most popular and least capable and you end at your least popular and most capable."

Few might have suspected that a prime minister who, in his decade in office, exuded such an appetite for power, harboured such regrets.

Mr Blair's predecessor, Sir John Major, who struggled to hold his government together as his party's long period of rule came to an unruly end in 1997, recalls how his premiership became intolerable as his small majority vanished.

"If you have a very small or no majority it is crippling of your time. You have to attend very late night votes, which prime ministers with a large majority don't have to do.

"You don't have to worry about sections of your party who are opposed to a particular policy because they're a minority, they're going to be outvoted. You treat them decently and listen to them, but you don't have to worry that they're going to upset the apple cart completely and defeat the government."

Sir John found some solace in his weekly audiences with the Queen. "They are utterly private. So it is an opportunity for both parties to speak in total frankness to one another. And in politics, except with people who are extraordinarily close, it is very difficult to do that. So it's a great outlet when prime minister and Monarch can meet."

What of the current incumbent? Boris Johnson strikes a characteristically ebullient note. "Number 10 has brilliantly evolved over hundreds of years into what is a big department of state now," he says.

Boris Johnson returned to Number 10 after his victory in the December 2019 general election

"And what you've got is a 18th century townhouse, which is rather beautiful. This is an incredible institution that has evolved over time into this extraordinary centre of a G7 economy."

It is obvious that the prime minister revels in the history of the building and, despite being in office during the worst pandemic in over a century, which almost took his own life, he relishes the job.

While Mr Johnson claims that he's supported by a "big department of state" in Number 10, many prime ministers feel they lacked institutional might, especially compared with the Treasury.

David Cameron told us: "Everyone thinks Number 10 is all powerful because it is the office of the prime minister. But of course Number 10 is very small - underpowered - compared to these massive departments of state.

"I remember joking after a few months that you spend far too much time trying to find what the government's actually doing and quite a lot of time trying to stop it."

Mr Cameron was criticised for "chillaxing" in the job, enjoying the trappings of Chequers, the prime minister's official residence in the Chilterns.

Lack of time and the relentlessness of the Downing Street diary afforded him little time off.

"I would often pop up [to the flat] and make a sandwich for lunch. Because you do need a bit of time to be able to be on your own and just think and just breathe. Just a few moments of peace at lunchtime and making a cheese sandwich. These were really valuable moments," he says.

Tony Blair has said "I don't think I did enjoy the job" of PM

For many incumbents of Number 10, survival in office was not just political - it was a matter of life or death.

While Spencer Perceval remains the only prime minister to be assassinated - in 1812 - others have been the targets of numerous attempts - notoriously Margaret Thatcher in 1984 and John Major in 1991, both targets of the IRA.

Others have left exhausted and ill, notably Anthony Eden and Harold Macmillan.

David Lloyd George nearly died of Spanish Flu in September 1918 only a few weeks before the end of the First World War. The seriousness of the condition was concealed from the public for fear that it might harm morale.

A century later, a stunned public was all too aware of the gravity of Boris Johnson's illness, when he was admitted to intensive care suffering with Covid-19.

Was Mr Johnson aware of the echoes with Lloyd George's near death experience during the last major pandemic? "Did he? I had forgotten that. I didn't get the Spanish flu. If you want to know, I'm feeling absolutely tremendous."

As a keen student of history and biographer of Winston Churchill, which of the prime minister's predecessors would he most like to meet and find common cause? Would it be Churchill himself, the choice of David Cameron? Might it be Sir Robert Walpole, the man who established the office and held it for longer than any other?

The PM's reply was surprising.

"I think Gladstone. I'd love to meet Gladstone," he says.

The Prime Minister at 300, presented by Sir Anthony Seldon and produced by Peter Snowdon, is on BBC Radio 4 on Friday at 11am and at the same time on Friday 9 and 16 April. It is also available on BBC Sounds.