What is lobbying? A brief guide

- Published

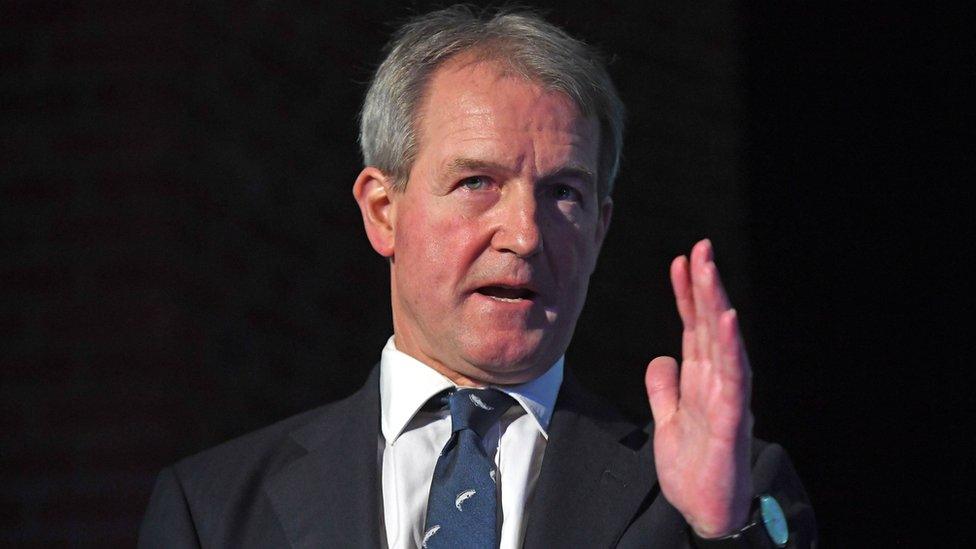

Tory MP Owen Paterson resigned his seat after being embroiled in a row around lobbying

Westminster has been bursting with rebellions, U-turns and resignations this week after the Tory MP Owen Paterson was found to have broken parliamentary rules on lobbying. But what does the term mean?

What is lobbying?

Lobbying is when individuals, businesses, trade unions, groups or charities try to get a government to change its policies. "Political persuasion" might be a better term.

How does it happen?

Lobbyists make their case to ministers, MPs or officials. They can write, email, text, phone, video call or turn up in person in Parliament to do it, although the latter hasn't happened much over the past two years due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Does lobbying work?

Not always. Changing politicians' minds can take a long time. That's why organisations and firms often hire professional lobbyists to make arguments on their behalf. Some of these are former politicians themselves and "know the game" - that is, who's who and where to find them.

But it's important to re-emphasise that individual citizens - unpaid - can also lobby politicians about issues that are important to them. Anyone can be a lobbyist, in other words.

So is the system fair?

Supporters say professional lobbying is a vital and valid part of democracy - that it stimulates debate and keeps politicians in touch with the latest developments in areas like science and business.

But critics argue that the current system is open to corruption and that wealthy interests - the ones who can afford professionals to make their case - have an unfair advantage.

What are the rules?

Ministers and top civil servants are effectively banned from lobbying their former colleagues for two years after leaving government. Lobbyists also have to join a register, which was set up by David Cameron as prime minister.

But Mr Cameron, who left Downing Street in 2016, became the centre of a row about lobbying earlier in 2021 over his work for Greensill Captial.

In Mr Paterson's case, he was found to have broken the rules by approaching and meeting officials at the Food Standards Agency and ministers at the Department for International Development a number of times over issues involving two firms he was a consultant for.

The Commons Standards Committee also said he used his parliamentary office and stationery for his consultancy work and failed to declare his interests in some meetings.

The commissioner decided that the contact with officials and ministers were "serious breaches" of the rules.

Is anything changing?

Following the disclosures about Mr Cameron's work, the government set up a review of lobbying, led by lawyer Chris Boardman.

He said some of the accusations that the government's processes for managing lobbying were "insufficiently transparent", had "loopholes" and allowed "a privileged to few have a disproportionate level of access to decision makers in government" were "justified".

But he said Mr Cameron did not break any of the rules.

After the incident involving Mr Paterson, the focus from the government was not on his lobbying but in the need for an overhaul of the system policing MPs' conduct instead - giving members more chances to appeal findings against them.

Initially, Downing Street backed an amendment to shake-up the watchdog and blocked Mr Paterson's suspension too.

But within 24 hours, and after a furious backlash from opposition MPs, No 10 U-turned, and now government is appealing to other parties to hold cross-party talks about any chances.

These would not be retrospectively applied to Mr Paterson's case though, and soon after the announcement, the MP resigned his seat.

Why is it called lobbying?

It started long ago when members of the public turned up in Parliament's lobby areas to let MPs know what needed to change.

It's harder to get into that part of the building than it used to be because of tougher security, so meetings are just as likely to take place elsewhere, such as over dinner, in MPs' constituencies or via the phone.