Lobbying row: Why ministers have two mobile phones

- Published

The lobbying controversy that has enveloped Westminster is a complex and fast-developing story but there is one strand running right through the centre of it - the smartphone.

WhatsApp and text messages have replaced face-to-face meetings and letters as the favourite method of communication for politicians.

The casual, and sometimes untraceable, nature of these communications can make it harder for the Civil Service to ensure everyone - ministers, officials, businesses and lobbyists - plays by the rules.

It wasn't that long ago that everything was typed out in triplicate, and phone calls were routed through Whitehall switchboards, with officials listening in and taking notes.

Tony Blair didn't get a mobile phone until he left Downing Street in 2007. Now politicians, like the rest of us, can't live without them.

Following a series of revelations about ministers' use of texts and messaging apps, Labour has warned that the UK is heading towards "government by WhatsApp".

Is that right?

It's a catchy slogan, but it might be a bit dated, as the prime minister and other leading politicians are reportedly migrating to Signal,, external a rival messaging app.

Users can set encrypted messages to automatically delete after short periods of time, even as short as five seconds.

They can also stop screenshots being taken of exchanges if they are using an Android phone.

Messages sent and received on Facebook-owned WhatsApp - which has been around since 2009 - are also encrypted, but screenshots can be taken and shared.

'I wasn't told how to use it'

Ministers are issued with work mobile phones when they get a job in government. Until a few years ago, they were given Blackberries, but now the iPhone seems to be the favoured brand.

The idea is to ensure that professional and personal calls, texts and emails are kept separate from their personal communications.

"I was given a phone as soon as I started," one former Conservative minister tells the BBC, "but I wasn't sat down and issued with any advice on how to use it."

A government source says: "Clearly ministers may have informal conversations from time-to-time, whether that is in person, via digital communications or remotely, and if they find themselves discussing official business then significant content from such discussions should be passed back to officials."

In official guidance, external, designed for private emails but applying to all electronic communications, ministers are told to work out whether they include details on "substantive discussions" or "decisions" made on government business.

If they do, they should then forward them to civil servants.

Are texts really meetings?

The ministerial code,, external laying out general rules of behaviour, says that a private secretary or another official should be present for "all discussions relating to government", to ensure transparency.

If that's impossible - such as when ministers chat to business leaders at social events - they have to report back to civil servants as soon as possible.

It's widely accepted that phone messaging should be reported in the same way if it's about important official business.

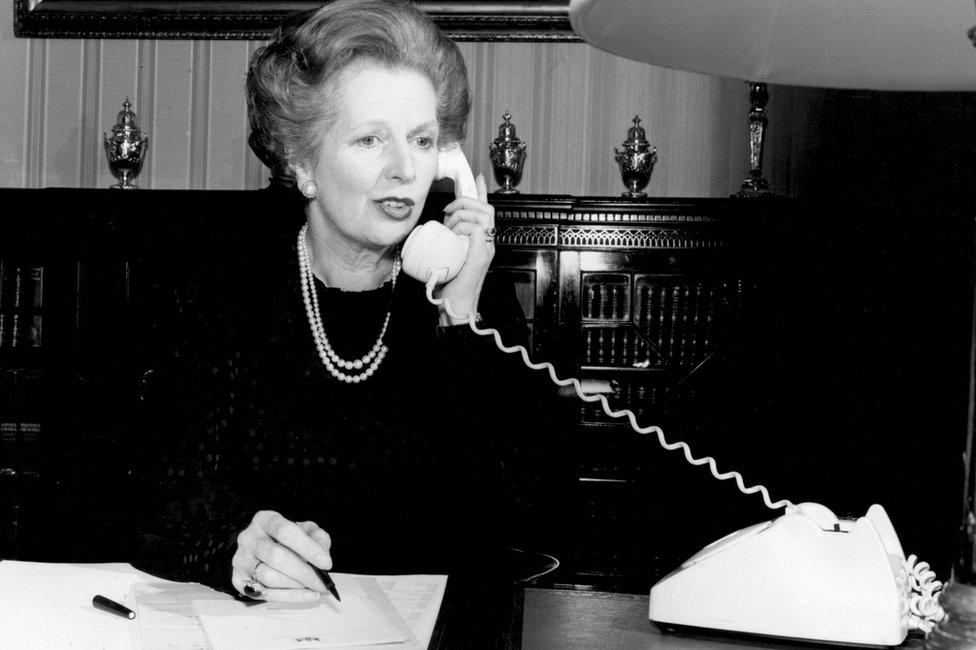

Communication was very different in Margaret Thatcher's day

But the Institute for Government (IfG) think tank wants a tightening of the rules, so that all messages sent and received on official phones - about whatever topic - are logged, with the names of those taking part published quarterly. This already happens for meetings ministers attend.

"There needs to a public record that something's happened," IfG associate director Tim Durrant says. "Texting's essentially a conversation, like a meeting."

'It's a free country'

A source who used to work in Whitehall in a senior role says it was "normal" for ministers to have text exchanges with business leaders - and then let civil servants know about them.

"There's nothing wrong with the leaders of this country talking to captains of industry," they add. "It's a part of how government functions. We live in a free country.

"What really annoys me is that there's an assumption of wrongdoing of some sort here. It's wrong to say government is run by text message. It's a form of communication that everyone uses for personal and official matters."

Culture minister Caroline Dinenage told Times Radio ministers did not hand out their mobile numbers "willy-nilly" and there were "very clear rules" about handing contacts to civil servants.

But Labour argues that the government's use of messaging fosters "cronyism", that those with ministers' phone numbers have an unfair advantage over those who do not.

'You need a phone'

An ex-minister tells the BBC they kept personal and official messages completely separate when they were in office.

"You have to rely on people using their common sense," they add.

"Some ministers actually hand the work mobile across to be carried by a special adviser or a member of their team, so they're not too close to it and don't use it in an inappropriate way.

"You've also got to be careful as to whom you give your number out to."

Some in government have suggested the prime minister should be less willing to share his personal contact details, the BBC understands, but officials have denied that he was told to change his number.

But Mr Johnson says he will keep his phone, arguing: "I need to be in touch with people... You need one these days."

And there would inevitably be resistance to any rule change among some in Whitehall.

One former special adviser asks: "What are ministers supposed to do? Put in a 30-page submission for every transaction they carry out, even in the midst of a pandemic?"