World War Two: How MPs survived the bombs and kept working

- Published

Winston Churchill went to survey the wreckage

There's a famous wartime photo showing the unmistakeable figure of Winston Churchill inspecting the ruins of the House of Commons Chamber, after it was destroyed by a German bomb in May 1941.

Nothing was left of the Victorian debating chamber graced by Gladstone and Disreali - so where did MPs meet for the nine years it took to rebuild?

The answer, kept secret at the time, was that, 80 years ago this week, they moved just a few hundred yards across the Palace of Westminster, and took over the chamber of the House of Lords.

The suggestion was first made by the radical Labour MP, Jimmy Maxton.

Peers readily agreed, and King George VI had to give his permission, because, ultimately, it was his chamber.

And once it was agreed, MPs switched from the green benches of the Commons, to the red benches of the Lords, without missing a beat.

"The Lords did the right thing, they said we want you to sit as a parliament," says the current Speaker Sir Lindsay Hoyle.

His opposite number, the Lord Speaker, Lord McFall said it showed the two houses of parliament working together to keep democracy doing.

The two posed with the Speaker's Chair used during this period, which was brought back to the House of Lords to mark the anniversary.

Sir Lindsay Hoyle and Lord McFall commemorate the historic swap

The Lords Chamber is the same size as the Commons' but much more splendid, dominated by the throne at one end.

But MPs soon found they were not moving to grander quarters.

Their new home was damaged too - another bomb that had crashed through the roof and then the floor of the Lords on the night the Commons was destroyed.

It failed to explode, but the cathedral-like stained glass windows which lit the chamber were shattered and had to be boarded up, so MPs took their new seats in pervasive gloom - "pretty much pitch black," according to the Parliamentary historian Elizabeth Hallam Smith.

And that was just the start of the problems; the debating chamber was turned round, so the Speaker sat at what is now the Bar of the House, facing the Royal throne, which was discreetly curtained-off for the duration.

More seats were added - enough for about 400 of the then 615 MPs, and carpets with lines ensuring two swords-length separation between the sides of the House were laid.

The combination of reversing the chamber and the bomb damage meant the room was draughty, the acoustics were poor, and MPs struggled to hear each other.

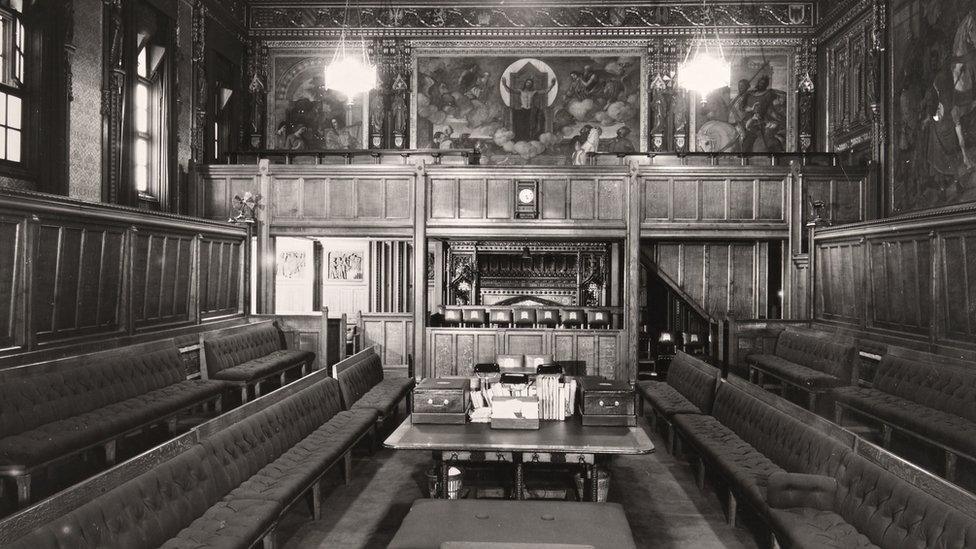

Peers moved to their temporary quarters 80 years ago this week

MPs moved to the Lords chamber

The lighting was dim and the heating seldom worked, but there was a war on, so honourable members had to make the best of it - although the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington was called in to help improve conditions.

Peers meanwhile, had moved down the corridor to a makeshift chamber set up in the Royal Robing Room - this is the ceremonial space where the Sovereign dons the crown for the State Openings of Parliament, and was quite large enough to accommodate the 45 or so peers who normally attended sittings of the Lords in this era.

Lord McFall takes some pride in their constructive approach to key legislation.

And there they mostly stayed for nine years.

Most of Churchill's greatest wartime speeches, "fight them on the beaches," "blood, toil tears and sweat," were delivered in the old Commons Chamber, but this was the venue in which the prime minister briefed MPs in secret session, and hailed the turning of the military tide.

It was this Chamber to which MPs returned after Labour's landslide at the 1945 election, and where the torrent of legislation which created the NHS and nationalised much of industry was passed.

A great deal of history was played out in the Commons temporary home - but one of the most important things was the symbolism; Parliament was not driven out of Westminster by the bombing, although the building suffered 14 major hits.

The refuge prepared for it in Stratford-upon-Avon was never used, and even though their exact location was kept under wraps, Britain's political leadership was not forced to retreat.