UK can be China-US peacemaker, says ex-minister Oliver Letwin

- Published

Sir Oliver Letwin was a leading member of a government that foresaw a "golden era" of relations with China, with the UK as its "best partner in the West".

Things have changed quite a bit since the then-chancellor George Osborne made this announcement in October 2015.

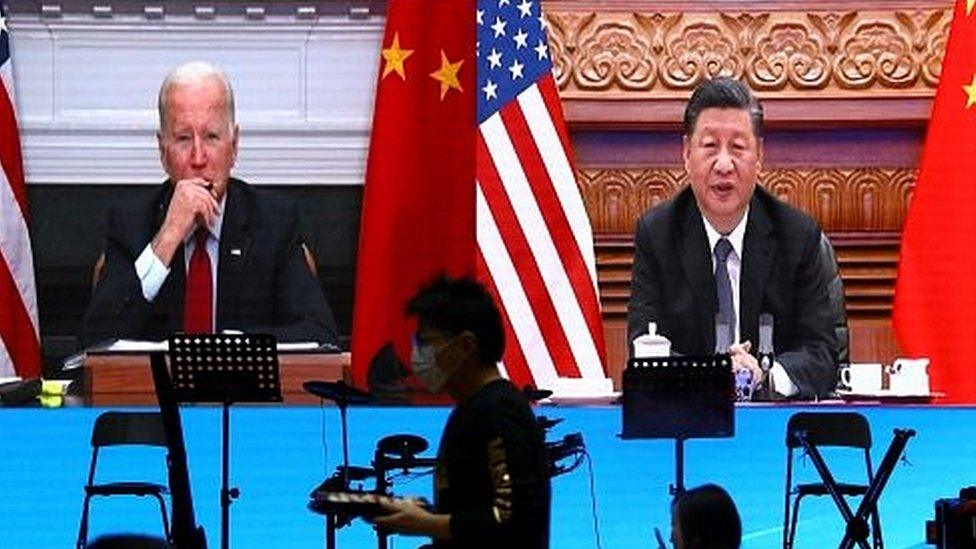

China and the United States, often seen as the UK's firmest international ally, find themselves at loggerheads, loudly and seemingly daily, over issues as wide-ranging as Taiwan's future, human rights, trade and the balance of power in the South China Sea.

Partly as a result of this, Sir Oliver, the former Cabinet Office minister, has spent a lot of time thinking about the the UK's place, and future role, in the world.

"We are very definitely in the third rank," says Sir Oliver, who campaigned against Brexit and was one of 21 Tory MPs to be expelled from the party for opposing Boris Johnson's plans.

"We're not the US or China. We're not India. We're not the EU."

But Sir Oliver - who has since returned to the Conservative fold but is no longer an MP - envisages the UK government working with the EU, Canada, Australia and New Zealand "to exert, collectively, some influence" over the US - the more accessible of the world's two superpowers - "constantly attempting to make sure that the rhetoric is reduced to a calmer level".

It has been anything but calm recently.

Joe Biden's government has angered Xi Jinping's by announcing a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics over human rights issues, with China promising "resolute counter-measures".

The US, UK and Australia have infuriated China by agreeing a security pact it views as an attempt to counter its influence in the hotly contested South China Sea.

Add to this a disagreement over whether Taiwan should be independent of China, and the US accusing China of genocide against the Uighur population in the province of Xinjiang and undermining democracy in Hong Kong, and there is no doubt the situation is volatile.

"I'm not wildly optimistic," says Sir Oliver, a visiting professor at King's College London, as he contemplates relations between the US and China. "On the current trajectory, we are heading pretty remorselessly into a cold war between America and China."

In his book China vs America: A Warning, he goes further, insisting China and the US must adopt a more friendly form of rivalry to avert a "hot war".

They can start, he argues, by talking seriously about problems such as climate change and disease, which they, like all of humanity, share a common interest in preventing.

Sir Oliver Letwin says China feels it deserves more respect from the West

But long-established institutions, such as the United Nations and International Monetary Fund, are inadequate, according to Sir Oliver. Reforming them would take "ages", so China and the West have to engage more immediately.

"I'm not claiming that that's certain to happen," says Sir Oliver, "but it just seems to be a sensible thing to try, because I can't think of anything else that's at all likely to build up the basis of trust between the West and China."

Many analysts in Washington argue that authoritarian China wants to destroy liberal democracy through its economic influence - such as the Belt and Road Initiative building infrastructure between Asia and Europe - and an increasingly aggressive military.

But Sir Oliver says the West often misunderstands China, whose primary aim is to restore what it regards as its rightful position as a world power following the "aberration" of the last 250 years, during which it has been largely subdued by the West.

"They expect to be treated with respect... and they don't expect institutions to kowtow to the United States."

The West should work to end "the maintenance of China's periphery", says Sir Oliver, in an effort to manage the "conflicting ambition" between China and US - that is, between gaining and retaining power.

Sir Oliver says the G20, external - a forum representing 20 leading economies, including China - shows promise, but the US must make a "very, very big adjustment" to no longer being the world's sole superpower.

China's activities in Hong Kong have raised concerns

Due to censorship, the former MP's views will not be as readily available in China as in the West, but what advice does he offer its diplomats?

"It's extraordinarily important the Chinese recognise what a big adaptation this is for the United States and recognise how profound that difficulty is on the other side," he says.

But many foreign policy thinkers would argue that the best - indeed, only - way to deal with China is not to show any weakness. Might not Sir Oliver's stance be taken by some as naive, placing too much onus on the West to change, without asking China to do the same?

Currently other Western nations are "just sort of adhering to whatever Washington says, and being increasingly hawkish. So at the moment we are not performing the role [of influencing policy] at all," says Sir Oliver.

"You could imagine the UK having a settled diplomatic strategy of surrounding the US with friendly allies who were counselling involvement and engagement in these joint endeavours to solve the big problems the world faces."

Earlier this year the US State Department accused Mr Xi's government of genocide, external against the Uighur people, including the use of internment camps, forced labour and sterilisation.

The UK government has announced it, like the US, will impose a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Games. over this and other abuses.

Several British MPs, including former Conservative leader Sir Iain Duncan Smith, have been placed under sanctions by Beijing after criticising the human rights record of Mr Xi's government.

They argue the UK government must go further in its condemnation and actions.

Sir Iain said recently that it "now needs to stop messing around", adding: "The genocide taking place in Xinjiang has got to dominate our relationship with China."

The crackdown on democratic campaigners in Hong Kong, a former British colony, is seen by Sir Iain and others as a harbinger of the type of influence China might try to exert in other countries.

But while he recognises that the West must continue to speak out over such behaviour, this does not deter Sir Oliver from arguing that dialogue is essential.

"We want to provide a continuing beacon of light on human rights everywhere," he says. "But that shouldn't stop us from wanting to do business with them in the interest of humanity as a whole."