What are whips and are MPs scared of them?

- Published

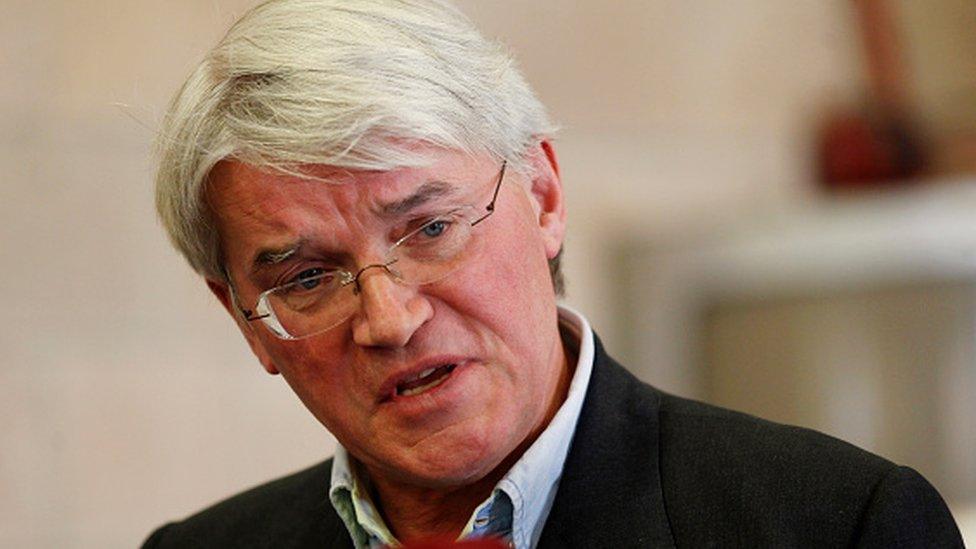

Francis Urquhart was depicted as a fearsome chief whip in the BBC's House of Cards series

The whips love their sinister reputation.

In fact, their job is a very basic one; they must ensure MPs vote in the way the party leadership wants, and (in the case of the government whips) see that the government gets its business through Parliament.

It doesn't have to be pretty, it just has to get done.

But it's easy to see why Machiavellian Francis Urquhart in the BBC TV series House of Cards could be viewed as a role model, rather than a villain.

Whipping is "a deed without a name" involving "the dark arts", and its practitioners deploy fiendish subtlety and precisely targeted intimidation like a combination of Sigmund Freud and Don Corleone.

What's a whip?

A whip is an MP who, as part of a team, is responsible for other MPs attending Parliament and voting along party lines

There are whips in the Commons and the Lords

Whips traditionally don't speak in debates or ask questions

In his recent memoirs, former Conservative chief whip Andrew Mitchell puts it like this: "A whip is not moral or immoral, but amoral.

"If the government decides to proceed with the Slaughter of the First-Borns Bill, it is the whips' job to secure the necessary votes by explaining that there are too many first-borns around, fettering the chances of the second and third-born children… 'it will go down particularly well in your constituency, have you not studied your own population statistics?'."

It's not a huge step from that kind of persuasion to more heavy-handed tactics.

Tory MP Andrew Mitchell describes whips as "amoral" in his memoirs

The former foreign secretary Jack Straw describes in his memoirs how, when he looked likely to defy the Labour Party line as a young MP in the 1980s, the legendary Labour whip Walter Harrison's attempt to dissuade him involved administering a painful twist to his genitals.

And as I write, hundreds of Westminster journalists will be digging into William Wragg's extraordinary allegations.

There is a more benign side to whipping, though. It's a kind of HR function, which involves helping MPs deal with all kinds of personal crises, from looming bankruptcy to divorce, or mental health issues, and very little of that seeps out into public view.

But the point here is that core whipping is supposed to be invisible. Government business is supposed to go through smoothly and efficiently, with the behind-the-scenes efforts which make it happen never exposed to the light. If strong-arm tactics become the story, they've failed.

When, during the Blair years, the Labour MP Paul Marsden objected to a dressing down from the then Chief Whip, Hillary Armstrong, he recorded the exchange and went public by giving a verbatim account to the Mail on Sunday.

No 10 was forced to put out a statement saying that dissenting backbenchers would be allowed to speak out on the Iraq war. At the time, it was an extraordinary thing to do, but these days MPs are more likely to go public if they think they're being mistreated.

Growing dissent

Of course, the Commons generation of 2019 have not had a normal start to parliamentary life.

For most of their time in parliament, they've been whipped by WhatsApp, so their relationship with their whip has been much more superficial. Now, at a dangerous political moment, that is starting to matter.

If the whips can't head off or suppress dissent, or stop eruptions by the likes of William Wragg and David Davis, it becomes harder to deliver the vote.

MPs should report intimidation tactics to the police, says William Wragg

There's talk that Tory dissidents are looking for an opportunity to register their discontent with a vote against the government.

The whips scan through the agenda for the week ahead looking for pitfalls - and they will be scrutinising very carefully right now.

- Published19 January 2022

- Published19 January 2022

- Published20 January 2022