What is going on with the partygate probe?

- Published

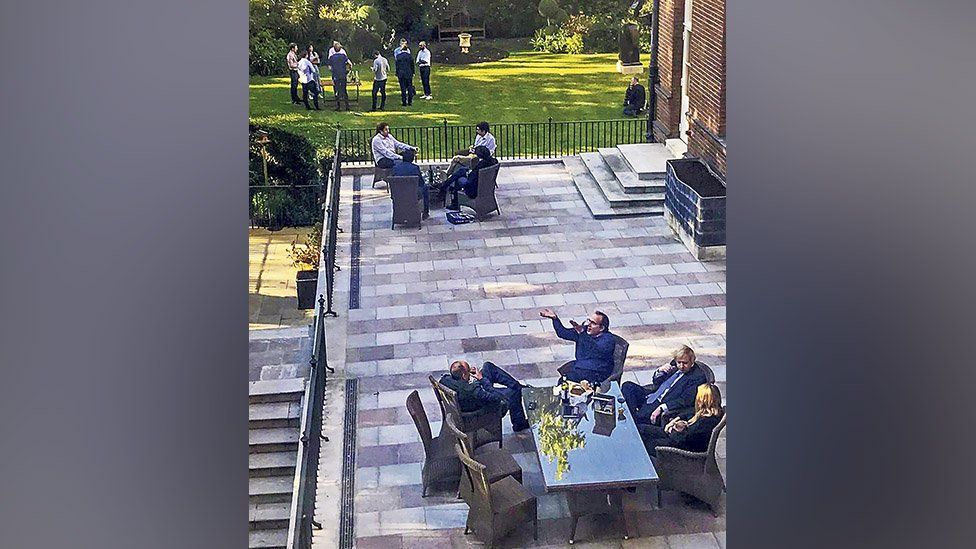

Before the war in Ukraine, lockdown parties in Downing Street had dominated the news. But while that's no longer the case, much is still going on behind the scenes.

We've been speaking to some of those being investigated, as well as some of the Tory MPs who may ultimately decide the fate of Boris Johnson, to understand what's happening, and predict what might happen next.

Partygate may have fallen away from the main headlines, but the Metropolitan Police's activities have been continuing under the radar.

Downing Street sources have confirmed more than 80 questionnaires have been received by aides, officials and politicians, asking about the events.

We have spoken to some of those who attended at least one of the 12 parties being investigated by the police. So far, no-one has said they have received a fixed penalty notice.

The Met has said it will reveal the number of fixed penalty notices it issues, and the nature of the rule breaches. But they haven't said when.

Naturally, some of those who attended parties have been sent questionnaires but, interestingly, some have not. This could mean the police are focusing their investigation on only "the most serious and flagrant type of breach", as then Met Police Commissioner Dame Cressida Dick indicated in January.

If that's the case, it may point to a high number of questionnaires turning into fixed penalty notices.

And it's not impossible the number of people caught in the net begins to grow. I'm told, for example, one civil servant who had been working at his desk while colleagues had been drinking was aggrieved to have received a questionnaire while his boss had not.

Whitehall sources have suggested there were fears among some staff that they might receive multiple fines if they attended more than one event under investigation, and some may face higher fines if they are deemed to have organised and not just attended an event.

So even if Mr Johnson isn't himself fined, critics say he may yet face renewed pressure to go if the scale of rule-breaking is, in the words of an ex-cabinet minister, "industrial".

It's still not clear when the Met Police will conclude their involvement. But events in Ukraine may be delaying the process.

Tory MPs

So what about Tory MPs? Before the conflict in Ukraine, the prime minister faced political danger. After a raft of allegations about rule-breaking gatherings during lockdowns, a dozen of his own MPs had publicly called for him to go, and more were considering moving against him.

He toured the parliamentary tea rooms, addressed meetings of his restless MPs, and the chatter in the Commons corridors was of little else.

What those Conservative MPs think of him is crucial. If 54 - 15% of the parliamentary party - lose confidence in him, then a vote would be held to determine whether he continues as Conservative leader, and therefore as prime minister.

But this week, a cabinet minister told me the war in Ukraine had changed everything.

Watch: What has Boris Johnson said before about alleged No 10 parties?

Before, speculation about his leadership had almost become "a self-fulfilling prophecy", he said. MPs faced with negative headlines might have been tempted to "lance the boil" and have a contest to clear the air.

But now, he said, the whole issue was barely mentioned. He believed Mr Johnson's leadership was safe. The cacophony of concern in the Commons corridors has been replaced with sombre silence.

Some MPs who hadn't called for Mr Johnson to go had been preparing to do so if he was fined by the police.

The prime minister's backers had become increasingly confident that this outcome could be avoided. He can claim No 10 is both his home and his office, blurring any lines between working and socialising.

But some now think he does not have to escape a fine to survive. Allies are arguing that "partygate" has now been put in perspective. One of them described the lockdown gatherings as "trivial" by comparison with war.

Another denounced the rhetoric and self-righteousness of some of Mr Johnson's opponents, adding: "What is 'sickening' is what Russia is doing in Ukraine, not whether the prime minister got a birthday cake on his birthday."

An MP, who wants Mr Johnson to go, said a protracted party leadership contest during a crisis was almost unthinkable, in part because there was not an obvious, single candidate - "no big beast, Hezza-type figure" - to replace him.

And, significantly, one former minister who had been on the brink of joining calls for the PM to step down, said he had now changed his mind.

"Even if he gets an FPN (a fixed penalty notice fine), those of us who were waiting for evidence of rule-breaking will certainly feel troubled, but we won't go after him." This was partly due to a feeling is that he has handled the conflict "OK".

Another was more blunt: any attempted putsch during the conflict would backfire, and the prime minister could win a leadership vote, with the pain of a contest for no obvious political gain.

And of course, with attention rightly focussed on Ukraine, even some of Mr Johnson's internal opponents concede that a recovery in the polls could disperse the political storm clouds around him.

Others believe that the underlying political climate hasn't dramatically changed.

Inside Downing Street

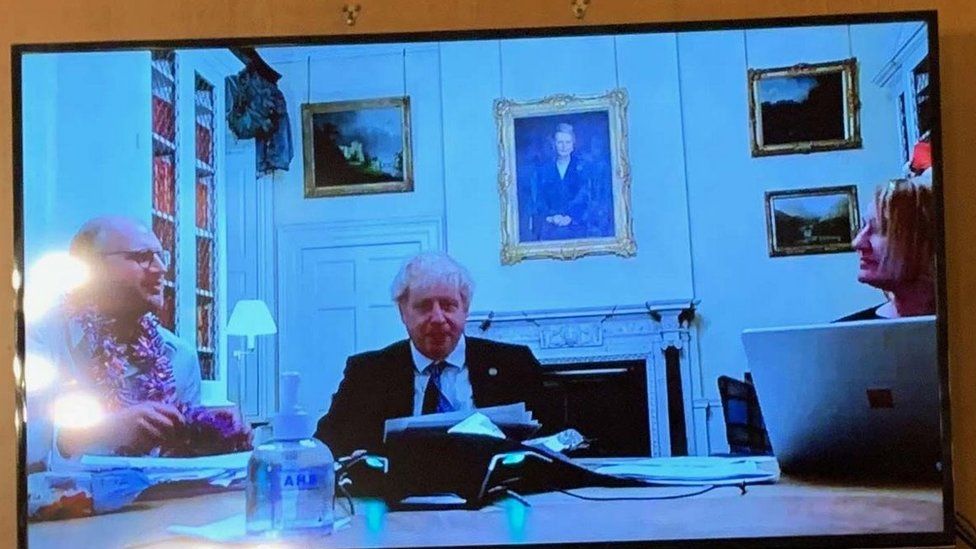

Mr Johnson's defence is that he has already begun reforming the way Downing Street is run - that some of the people who organised and attended the controversial events have moved on, or left government entirely - and there is a new chief of staff, a new communications director and new ways of working.

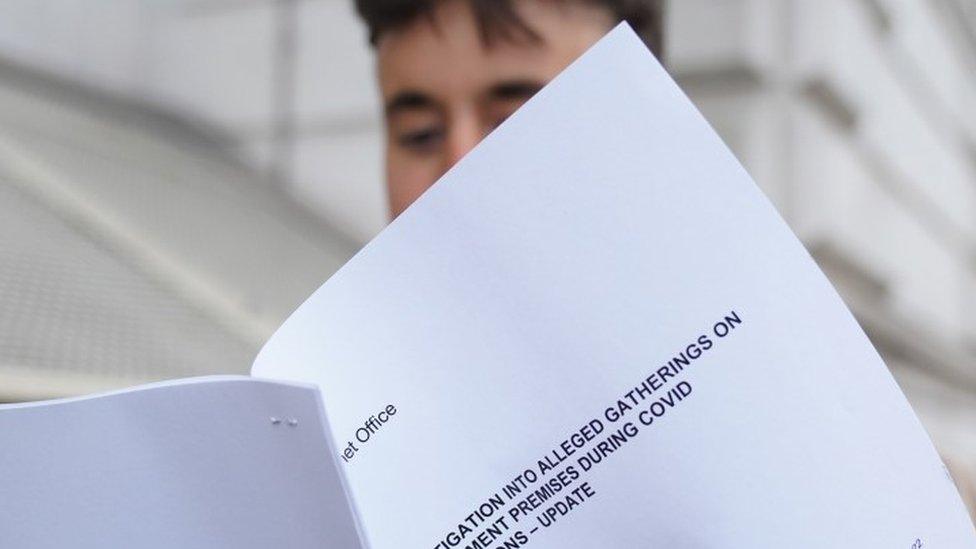

Sue Gray delivered an initial update at the end of January

But the effects of partygate may still have a long tail. I'm told there is resentment among some officials that while the prime minister and senior civil servants have paid for their own legal advice when completing the Met questionnaires, no assistance has been given to those who can't afford to do so.

Some of those who have received questionnaires have been subjected to the highest level of security clearance and genuinely do not know if a fixed penalty notice would mean they couldn't continue in their roles.

And if the prime minister escapes a fine but a whole swathe of more junior staff look like the "scapegoats", then that too could be politically difficult - playing to the opposition narrative that there is "one rule for Boris Johnson and another for everybody else".

The prime minister has returned his questionnaire - but with the focus at the heart of government now on the Ukraine crisis, some officials have asked for an extension to the seven-day window for their responses. And I'm told the Met has granted this.

It is also not clear yet if the process will be elongated if some people challenge the fixed penalty notices they receive in court.

What's next?

A former cabinet minister has come to the conclusion that "the longer the whole thing takes, potentially the higher the danger" for the prime minister.

If a fixed penalty notice were to be issued "in the next few days", it would get little traction, he told me, but it could become more toxic if and when coverage of the conflict in Ukraine dips.

"I'd say he has had a deferral rather than a reprieve," the ex-minister said. "The timescale moves beyond May and maybe even until October, December - depending on events in Ukraine. But the underlying concerns remain."

Two factors could still damage Mr Johnson's leadership, according to one Conservative rebel.

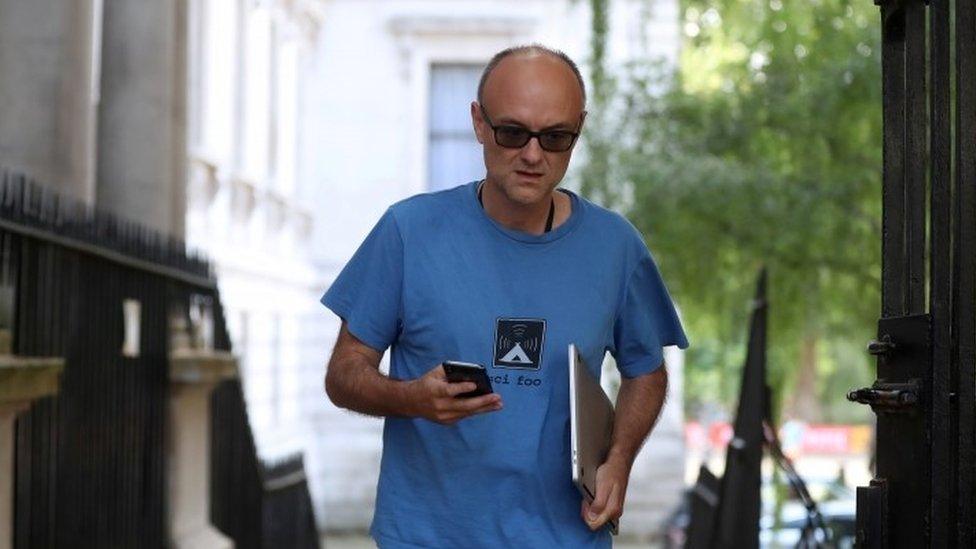

One MP says he's received more emails about Downing Street parties than Dominic Cummings's (pictured) trip to County Durham

First, public reaction. He doesn't accept the argument that because voters are focused on the suffering in Ukraine, that they have "forgiven" the prime minister for partygate - or forgotten it.

"This issue only looks trivial at Westminster. I had a deluge of emails about it in my inbox. Far more than over Dominic Cummings," he said - a reference to the PM's former adviser's infamous lockdown trip to County Durham.

So, when an unexpurgated version of the report by the senior civil servant Sue Gray is published, after the police investigation has concluded, this could provide a focus for more public anger, he argues.

But for him, the issue of whether the prime minister receives a fixed penalty notice or not is something of a red herring.

He believes that what may yet bring Mr Johnson down is not attendance at certain gatherings, but whether he has misled Parliament - and breached the ministerial code. The prime minister has been careful in his language.

In December, in the Commons, he told Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer: "I have been repeatedly assured that the rules were not broken."

'Lucky'

Now, such caveats may not wash with Mr Johnson's critics. But while the ministerial code states that "ministers who knowingly mislead Parliament will be expected to offer their resignation", that resignation would normally be tendered to none other than the prime minister - who ultimately interprets and enforces the code.

Ultimately, whether Mr Johnson remains in office will be a political, not a legal or procedural decision. And, right now, his position feels less precarious than it did.

A former cabinet colleague of Mr Johnson's said that the "talk in the [House of Commons] tea room is how lucky a politician Boris Johnson has been".

Then, after a slight pause, he added: "I remember they once said the same about David Cameron."

Related topics

- Published6 March 2022