Fertilisers: UK to reward green farming practices as costs surge

- Published

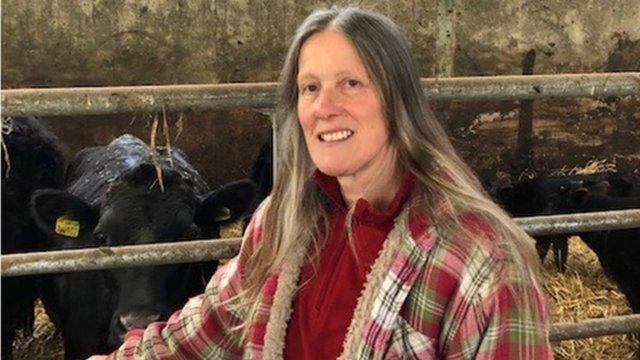

Farmers use fertilisers to grow crops but have been facing rising costs in recent months

The UK government will pay farmers in England to use greener fertilisers as global economic shocks send crop-growing costs soaring.

A spike in gas prices has left British food producers facing surging costs for fertilisers, fuel and animal feed.

The industry has warned this could lead to food shortages.

To help with costs, ministers are expected to set out cash incentives on Wednesday, aimed at farmers who move away from gas-dependent fertilisers.

"The significant rise in the cost of fertiliser is a reminder that we need to reduce our dependence on manufacturing processes dependent on gas," Environment Secretary George Eustice said.

But some farmers have called for more support with the rising cost of fertilisers, which they use to grow crops such as wheat, vegetables and pulses.

Some have told the BBC they are thinking about drastically scaling down crop production and warned of a "food crisis" should the price of fertiliser continue to rise.

In a letter to Mr Eustice, MPs highlighted a report that showed fertiliser price increases of up to 140% over the past year, with the cost of a tonne rising by £350 since February.

Rising wholesale gas prices - exacerbated by the war in Ukraine and disruption of energy exports from Russia - have increased the production costs of manufactured fertilisers for farmers.

Natural gas is a key component in the production of manufactured fertilisers.

Synthetic vs natural fertilisers

Fertilisers are materials that can be added to soil or plants to provide nutrients and promote growth

Natural fertilisers are organic products that have been extracted from living things, such as animal manure

Synthetic fertilisers made up of chemicals and are usually manufactured from petrol or natural gas

Payments for using greener manures and other more environmentally friendly farming practices will form part of a new government scheme.

The Sustainable Farming Incentive scheme will replace existing grants for farmers and reward them for managing their land in an "environmentally sustainable way".

The government says the scheme is part of a wider package of farming measures designed to "address uncertainty" among farmers ahead of the coming growing season.

The government is expected to announce a delay of at least a year to planned changes to the use of urea fertiliser in England.

Urea fertilisers emit ammonia, a pollutant that the government says can "cause significant long-term harm to sensitive habitats".

A consultation on restricting their use and reducing ammonia pollution in the air was launched a year ago.

At the time, the National Farmers Union (NFU) called for an "industry-regulated approach" to what it described as a "vital product to grow the nation's food", whereas the government had pushed for a ban on the product.

However, the BBC understands the government will push for restrictions on ammonia emissions instead of a complete ban on the fertiliser.

The government is also expected to put out new legal guidance aimed at lowering pollution from spreading slurry, a natural fertiliser made from manure and water.

Grants will also be offered to help farmers store organic slurry and reduce their dependence on artificial fertilisers.

Farming fears

Andrew Brown, a farmer in Rutland, Leicestershire, grows about 400 acres of arable crops, such as wheat, barley, beans and linseed.

He said the increased costs of fertiliser and fuel had put "about £100 a tonne on my production of wheat".

"I produce about 1,000 tonnes of wheat, so that's put £100,000 on my cost of production, and I'm quite a small farm," he said.

Mr Brown said he was now going to "take half my farm out of production to put it in an environmental scheme". He said lost production in the UK would probably have to be made up from imports from abroad, where environmental standards can be lower.

But he feared there was not enough green manure to replace mineral fertilisers and that using a "muck spreader" would destroy his crops.

Andrew Brown said rising costs have forced him to scale down his farming operation

John Charles-Jones, who is an arable farmer in Nottinghamshire, said the winter wheat and spring beans he produces rely on fertiliser for a maximum yield.

He said "thankfully" he has enough in stock to last him this year, but price rises mean "the big problem will come next year".

He added: "If there isn't a food crisis yet, absolutely there will be." With price rises happening globally, "import[ing] our food from elsewhere" would not fix the problem, he said.

He said farmers were having to make decisions about whether to save some fertiliser for next year and produce less this year, and even whether to plant some crops at all.

"Once you've planted your crop you're committed to using it - if the price you then get for your grain is lower you could easily find a situation where you are out of pocket."

John Charles-Jones said there "absolutely there will be" a food crisis if fertiliser prices continue to rise

He said, "in theory", it would be "wonderful" to use organic fertilisers instead, but he was worried there was not enough. His farm was not set up to have livestock and these were changes that "you can't just have at the snap of a finger", he said.

Speaking to LBC radio on Monday, NFU President Minette Batters said: "If farmers and growers decide to grow less we will have shortages… farmers can't keep producing food well below the cost of production.

"Russia is the largest exporter of nitrogen fertiliser - no one yet knows who will fill that gap."

Related topics

- Published22 March 2022

- Published10 March 2022

- Published18 February 2022