Ministers to get power to block release of serious offenders

- Published

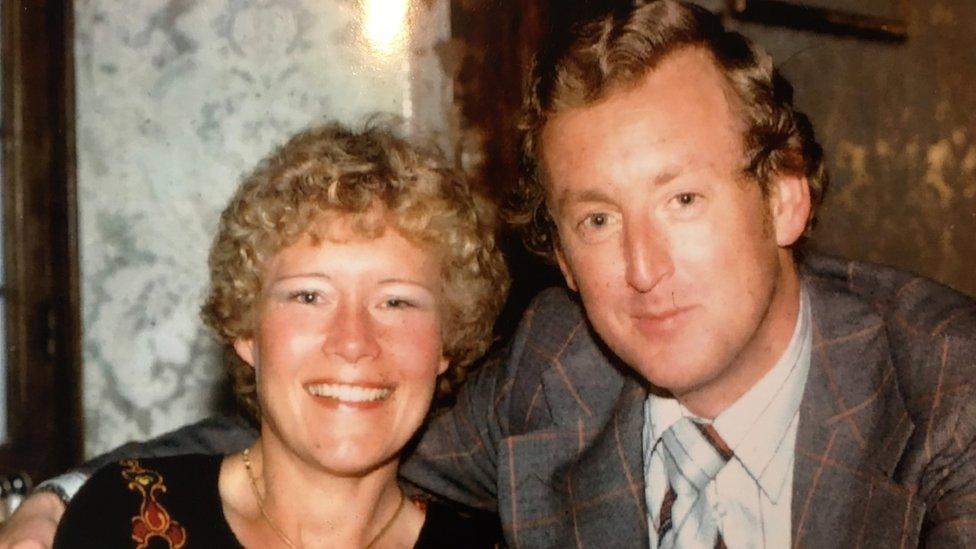

Concern over the release of John Worboys led to a review of Parole Board system

Ministers will get powers to block the release of serious offenders, as part of changes to the Parole Board announced by the justice secretary.

Dominic Raab said recent decisions by the board had eroded public confidence.

The minister also said he wanted to see more people with law enforcement experience involved in the process.

And he said he would be asking the Parole Board to reconsider a decision to release Tracey Connelly, the mother of Baby P.

The 246 members of the Parole Board of England and Wales make risk assessments and decisions on whether prisoners can be safely released or moved to an open jail.

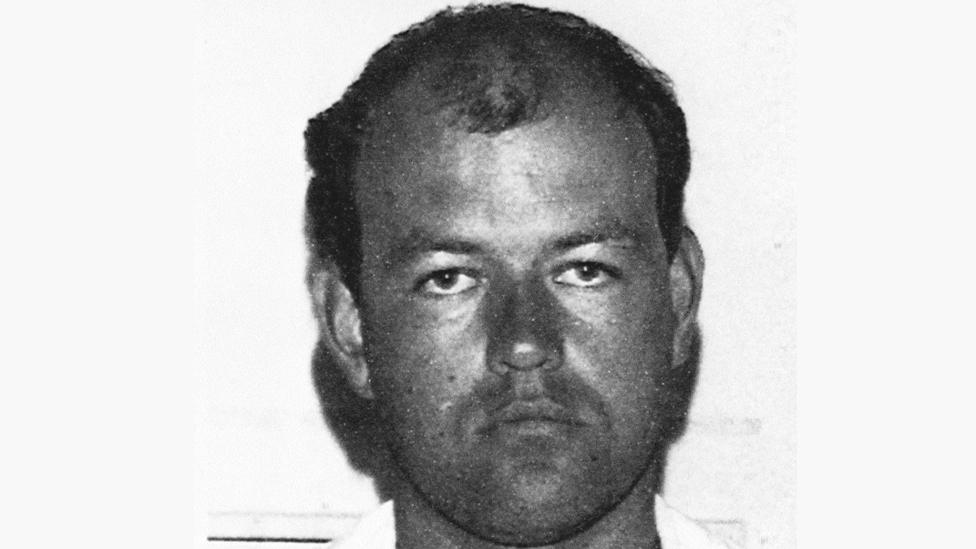

A review into the board was launched by the government after the release of the so-called black-cab rapist John Worboys prompted a public outcry.

The decision to release Worboys - who had been convicted of 19 offences against 12 women - was later quashed in court leading to the resignation of the Parole Board chair.

Citing the Worboys case among others, Mr Raab said the case for reforming the board was "clear and made out".

Speaking in Parliament, he said: "In recent years a number of decisions to release prisoners has led to disquiet and regrettably an erosion of public confidence."

Under the proposed changes the Parole Board would be able to refer cases to the justice secretary if they could not "confidently conclude" that the tests for releasing an offender had been met.

The justice secretary would also have the power to refuse release of serious offenders such as those convicted of murder, rape, terrorism and causing the death of a child.

'Quite a legal shift'

These proposals come as Dominic Raab says he will try to challenge a Parole Board ruling that Tracey Connelly, responsible for the death of her own child, is safe to be released.

And that story gets to the heart of the tension in the system.

The Parole Board is basically a court - a judicial process independent of politics but with a clear duty to keep the public safe.

Dominic Raab said the public expect ministers to protect them and so he's pitched his package as proportionate reforms to meet that end.

Creating a new power in which ministers can veto the release of some offenders convicted of murder, rape, terrorism or causing the death of a child is quite a legal shift.

Over the decades Parliament has taken that power away from them in a constitutional move to keep politics out of justice.

It's possible the package could conflict with human rights laws.

Mr Raab acknowledges that - and says that his separate plans to rewrite the Human Rights Act will make his reforms water tight.

Mr Raab said it was "striking" only 5% of Parole Board members came from a law enforcement background, and that the government wanted to recruit more people with such experience.

Victims will also be given greater participation in the process, with a requirement on the Parole Board to take into account submissions made by victims.

Labour's shadow justice secretary Steve Reed said he broadly welcomed the changes, adding that too many victims felt their views were "not taken sufficiently into account either in parole decisions or in sentencing".

However he questioned whether ministers could be trusted to make the right decisions on parole, noting that the justice secretary had approved the decision to move sex offender Paul Robson to an open prison.

Mr Robson escaped from North Sea Camp, but was later caught and sentenced to eight months for absconding.

- Published20 October 2020

- Published24 November 2021

- Published31 March 2021