How UK Greens are learning from overseas allies

- Published

Scottish Greens co-leader Lorna Slater is among those to have sought advice from foreign allies

As the environment takes a greater role in shaping our politics, green parties are getting used to sharing power worldwide. What have Greens in the UK learned from them?

Fifty years ago, the seeds of green party politics were planted in the pages of an obscure environmental magazine.

Writing in the Ecologist, a group of scientists and activists launched a movement they hoped would be "emulated in other countries, thereby giving rise to an international movement".

In time, their aspiration came to pass as political parties rallied to environmental causes globally.

One of the first was founded in the UK and became the Green Party, which split into three separate branches, with one covering England and Wales, another Scotland, and a third Northern Ireland.

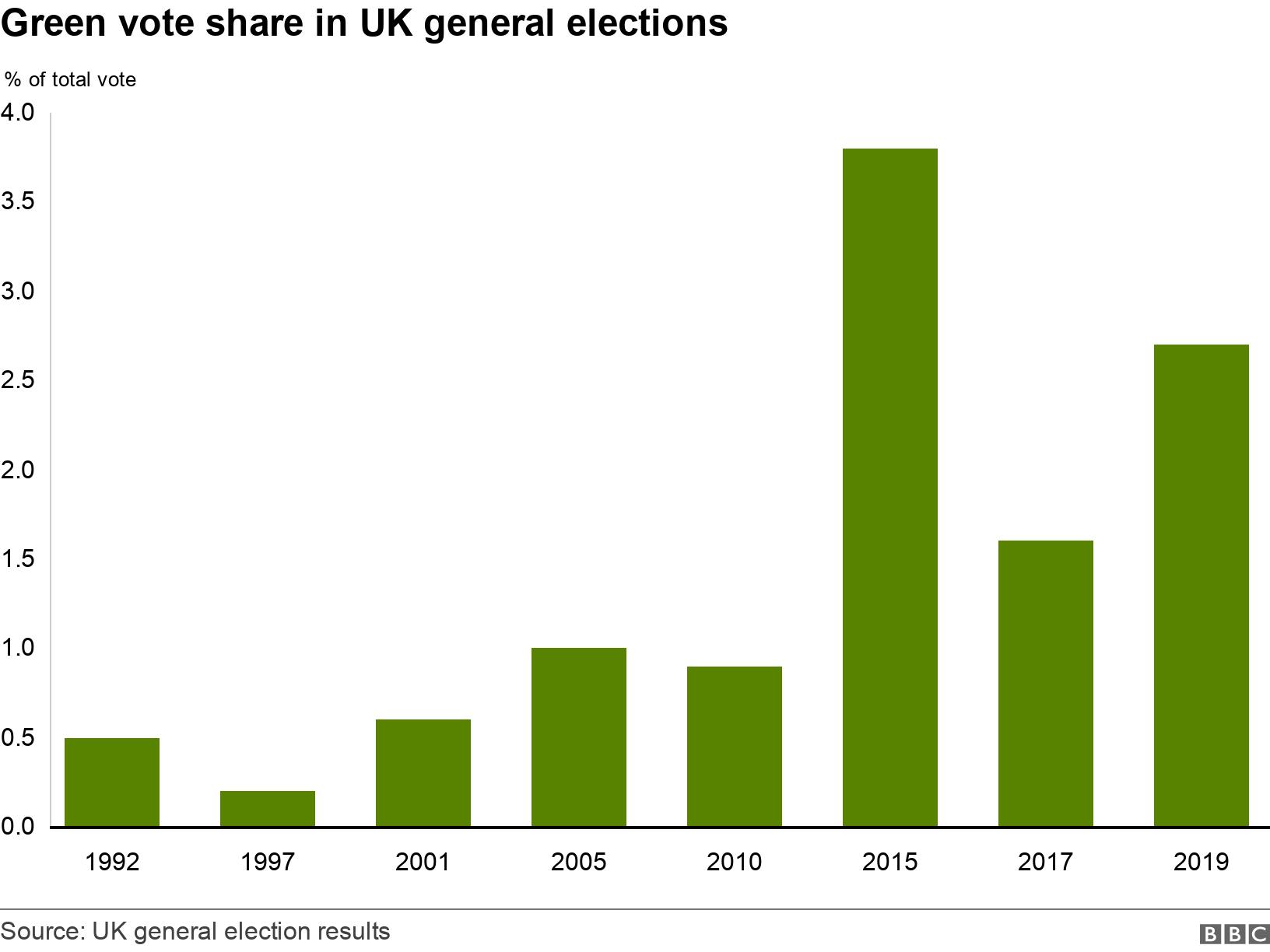

While their support has always been modest compared to the bigger parties, the Greens have been buoyed by recent successes and those of their foreign counterparts.

I wrote about the the growing momentum of green parties in Europe following the German federal election last year.

The German Greens won 14.8% of the vote nationwide and struck a deal to share power, as their sister parties had done before in other countries, from Finland to Austria.

Their British allies have not reached such heights since 1989, when the Green Party UK won 14.5% of the vote in European Parliament elections.

As they watch their allies govern from afar, the Greens in the UK have been embracing the internationalist spirit of their origins.

In meetings and calls with overseas partners, intelligence has been shared, and electoral strategy has been compared. As the Greens look ahead to the next general election in the UK, what have they learned, and will it help them achieve the big breakthrough they have longed craved?

Obvious parallels

To find allies in government, the Green Party of England and Wales does not have to look further than Scotland.

The Scottish Greens have been sharing power with the SNP since 2021, following elections to the devolved Scottish Parliament.

As both parties support Scottish independence from the UK, they partnered up to make a majority in the parliament and negotiated a co-operation deal.

It was uncharted territory for the Greens, who had never been in government anywhere in the UK.

As they hammered out their deal with the SNP, the co-leaders of the Scottish Greens - Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater - turned to New Zealand for guidance.

The Scottish Greens entered government with the SNP as part of a co-operation agreement

The Greens in New Zealand have been in government with the Labour Party since 2017. Following the last election in 2020, the Greens retained ministerial roles under a limited power-sharing arrangement with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern's Labour, which won a landslide victory.

To Ms Slater, the parallels between Scotland and New Zealand were obvious.

"I had the New Zealand Green leaders on my phone. I just messaged them," she said.

Video meetings were set up on Microsoft Teams and "we had some conversations where they gave us some advice", Ms Slater said.

"Then they gave us their copy of their co-operation agreement, so we could start seeing whether that was the right model. We talked about some of the challenges they had, the challenges of moving from being an opposition party to a party of government."

First-past-the-poster girl

Elsewhere in the UK, the Green Party of England and Wales has been wrestling with a different set of challenges. Like the Scottish Greens, the party has taken cues from their opposite numbers in New Zealand.

The election of Chloe Swarbrick particularly piqued their interest. In a stunning coup for the New Zealand Greens, the 27-year-old fashion designer won the coveted seat of Auckland Central in 2020.

Her election to New Zealand's Parliament at the age of 23 and subsequent "OK boomer" jibe had already burnished her political profile.

Watch how Chloe Swarbrick shuts down heckler

This time though, she won a seat under first-past-the-post voting, something only one Green MP had managed before in New Zealand, which has a mixed electoral system.

In first-past-the-post voting, which is used for UK general elections, the candidate who receives the most votes wins. It's straightforward enough, but smaller parties have long complained of wasted votes and unfair representation.

If Greens were pessimistic about this voting system, Ms Swarbrick's victory may have confounded their expectations. Was it more than just a one-off, though? The co-leader of the Green Party of England and Wales seemed to think so.

With a young electorate, Auckland Central is demographically similar to Bristol West in south-west England, where Carla Denyer hopes to become her party's second MP, joining Caroline Lucas, the Green MP for Brighton.

Ms Lucas has won the Brighton Pavilion constituency at every general election since 2010, increasing her majority each time, although the Lib Dems have not stood against them since 2017 as part of a pact.

The Greens have historically done best in urban areas with younger populations, such as Brighton, where their left-wing and eco-friendly policies have resonated with voters.

Shortly after New Zealand's election in 2020, Ms Denyer and her colleagues had a Zoom call with some of Ms Swarbrick's team.

"It was reassuring to hear they'd been doing similar things," Ms Denyer said, citing her party's visibility within communities as one example.

Her message to voters is: the Greens can win under first-past-the-post in the UK - and recent election results in Australia demonstrate how.

Comparing notes

Of the four Australian Green MPs elected in May's federal elections, three were in the traditionally conservative state of Queensland.

A few decades ago, Australians "would have found that deeply astonishing and puzzling", said Natalie Bennett, a former leader of the Green Party of England and Wales.

Now a peer in the House of Lords, she was born and raised in Australia before moving to the UK, where she entered Green Party politics.

The Australian Greens made gains in Queensland in May's federal elections

In a country that has suffered years of catastrophic wildfires, climate change was the defining issue of those elections in Australia.

"What's also happening is a different way of doing politics," Baroness Bennett said.

On an international level, those politics reflect the core values enshrined in the charter of the Global Greens, external, a network of political parties. United by democracy, social justice and sustainability, the network connects parties through working groups, outreach and conferences.

"So we have lots of opportunities for comparing notes on electoral strategy and also on policies, where we can learn from each other's successes," Ms Denyer said. "That's an important part of the green movement."

Learning from each other is central to the green ethos, as Baroness Bennett explained. On the week of our interview, she had a meeting with the French Greens ahead of parliamentary elections in their country.

The head of elections for the Green Party of England and Wales has not been short of appointments either.

"If anything we are giving advice to others on local elections," said Chris Williams. "We've had approaches in the past from Norway, Sweden and Greece."

Green ambition

Still, the UK's three green parties have only ever managed to get one MP elected between them at Westminster.

To win more seats at the next general election in the UK, the Greens need to strike the right balance between discipline of messaging and authenticity, Mr Williams said.

Even then, the left-wing Greens are aware of their limitations in the UK's two-party dominated system.

On climate change, the Conservative government and Labour have embraced the policy of curbing carbon emissions to net zero, making them more appealing to green-minded voters.

As competition for these voters grows, the Greens are taking a more targeted approach, with policies such as a universal basic income and rent controls.

The Green Party is "more focused than we ever have been in shifting the resources that we do have" into key constituencies, Mr Williams said.

"If it goes well, it's not inconceivable that the Greens could be in a hung parliament situation."

A hung parliament would mean no party had won a majority of seats. If Labour were to win the most seats, but fall short of a majority, they may need the support of the Greens to form a government.

At least, that's the scenario Greens are hoping for.

Adrian Ramsay and Carla Denyer have been leading the Green Party of England and Wales since 2021

Should the party be in a position to influence the formation of the next UK government, would electoral reform be its top demand?

Yes definitely, Ms Denyer said, "that would be one of the things I would want to change".

Even without that, the Greens believe they can follow in the footsteps of their international allies, as their movement envisioned at its genesis.

"Greens have shown that in several countries around the world and that's what we intend to do at the next general election," Ms Denyer said.

Related topics

- Published22 October 2021

- Published6 May 2022

- Published15 October 2021