What's the political mood following by-election dramas?

- Published

Watch: Moments that made this by-election historic

This is an important mood-making week for our biggest political parties.

Encounters with the electorate always mould the mojo of our political leaders.

For when you are in the popularity business, the verdict of voters, however geographically piecemeal, can't be ignored.

But there can be other catalysts that prompt a smile or a frown, and both the Scottish National Party and Northern Ireland's Democratic Unionist Party each face one of those moments in the coming days too.

But let's take a look first at the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats.

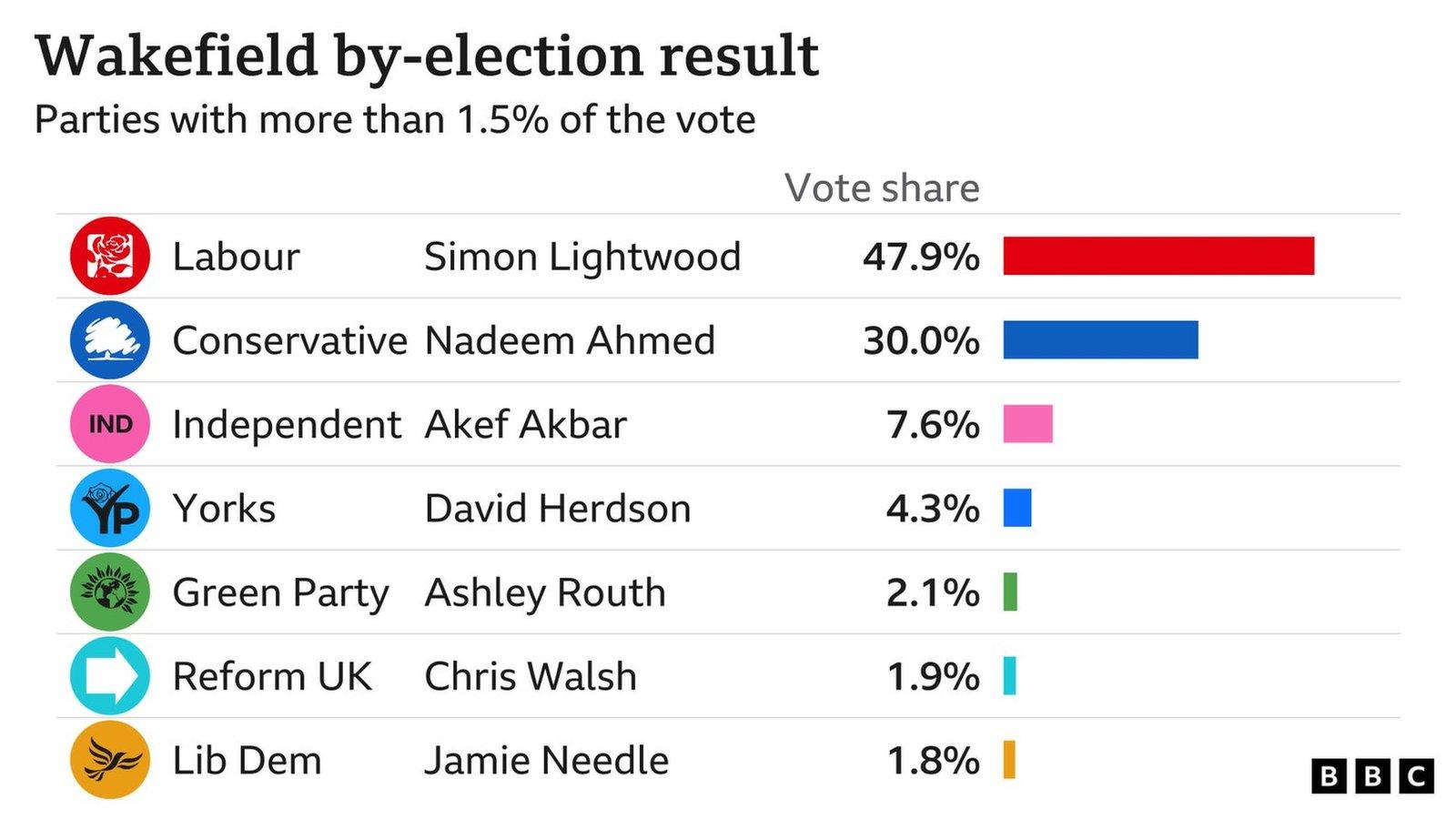

The result in Wakefield in West Yorkshire was less surprising but more important than the one in Devon.

Why? Because if Labour are to win a general election they need to take seats, and lots of them, from the Conservatives.

The party is pleased that, were the margin of Labour's victory there to be repeated at a general election (a big if, as they acknowledge, as by-elections are not about electing a government), they would have won a majority.

They take issue with the election guru Sir John Curtice's analysis.

Professor Sir John, of Strathclyde University, said the result implied there was still a question mark about the electorate's enthusiasm for Labour, as opposed to distaste for the Conservatives, given the decline in the Conservative vote was more than twice as big as the rise in the Labour vote.

Senior figures point out that plenty assumed when Sir Keir Starmer became Labour leader that such was the electoral mountain the party faced, he would never himself make it to Downing Street, but instead make it possible for his successor to do so.

"The mantra in the office is we have to be Kinnock and Blair," says one source, a reference to Lord Kinnock's rebuilding of the party and Sir Tony's delivery of an election victory.

They believe such a victory is now seen as doable.

Another source recently described the Starmer project thus far as "climbing out of the grave" dug for them by former leader Jeremy Corbyn.

Parts one and two of the plan were detoxifying their brand, as they saw it, and portraying the government as inept.

They feel they have done both these things.

The third stage, which plenty of figures including influential ones in the shadow cabinet are getting impatient to see, is the case for why people should vote Labour.

The investigation by Durham Constabulary into alleged Covid law breaking by Sir Keir and his deputy Angela Rayner has hamstrung that and it won't begin in earnest until - if - they are cleared.

Planning is under way for the party conference in the autumn; after last year's focus on internal Labour machinations, this year's will be about their pitch to the country.

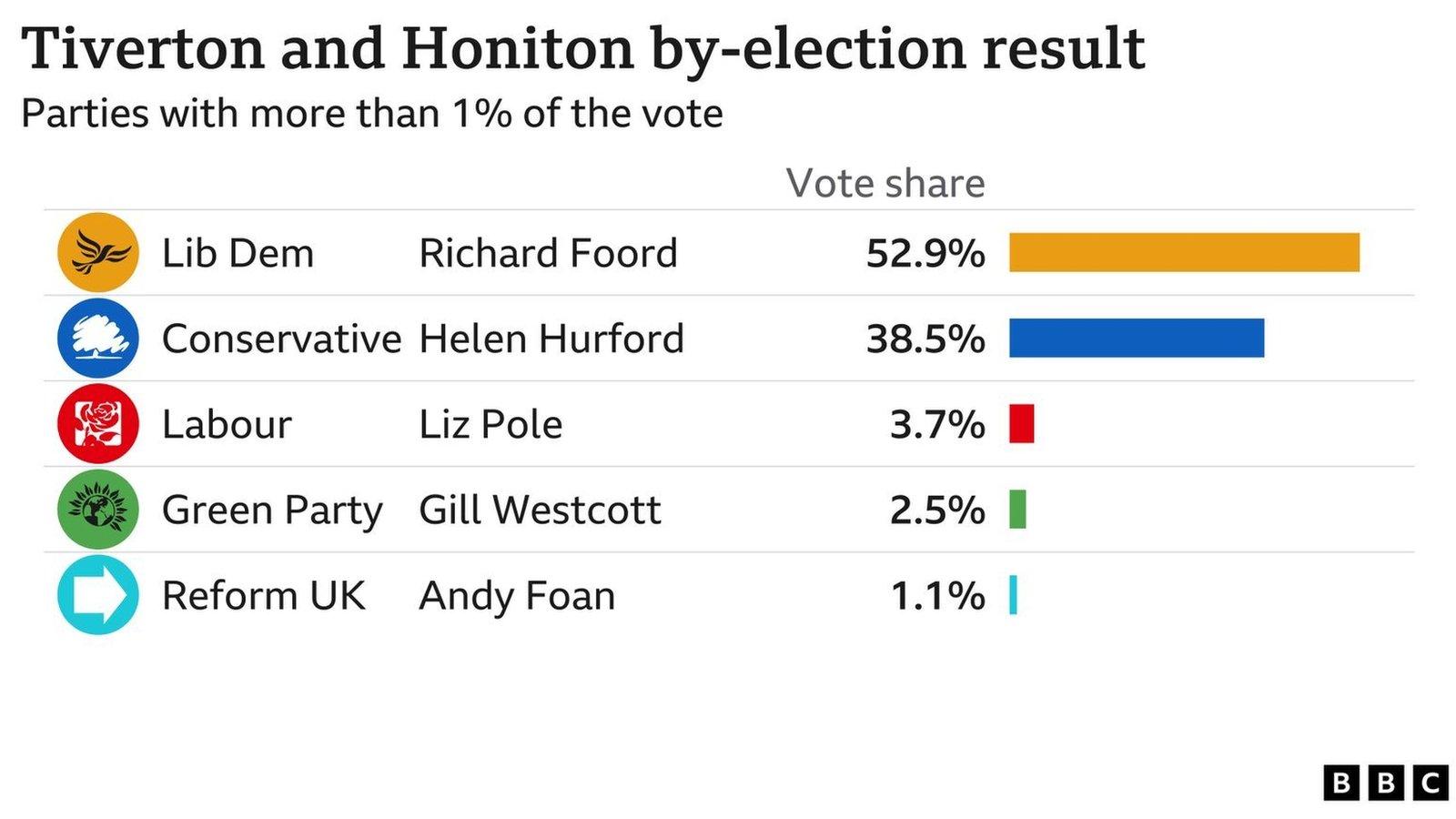

What, then, of the Liberal Democrats?

They, in the words of one, are "super chipper" this weekend.

Little wonder; a third whopping win against the Conservatives in a by-election a year.

Conservatives have been known to privately describe Lib Dems as the 'yellow peril', a backhanded compliment to their by-election savvy, energy and ruthlessness.

The coalition years doused their brand in a political poison for many.

The antidote of time appears to have washed much of that away.

They are still parliamentary tiddlers - 14 MPs out of 650, just 2% of the Commons.

Lib Dem leader Ed Davey joined his newest MP Richard Foorde to celebrate his win

But they could play an outsized role in the politics of the next few years, injecting fear into the Conservative psyche about their potential capacity to wipe out swathes of Tory MPs.

One thing the Lib Dems are irritated by is the grumbles of Conservatives, most notably the Health Secretary Sajid Javid this weekend, about talk of a deal between the Lib Dems and Labour to work together to eject Tory MPs.

As Sir John Curtice has said, there appears to be a growing willingness of voters to vote for whichever party locally is best able to beat the Conservatives.

Both Labour and the Lib Dems insist there is no deal, there is no pact, it's parties focusing on where they can win.

Lib Dem sources also point out they couldn't possibly have won and won so big in three previously rock solid Conservative seats without luring former Tory voters to them, including, especially in Tiverton and Honiton, plenty who voted Leave.

Next: the Conservatives.

It's 30 years since a party lost two by elections on the same day. The last time it happened, it was the Conservatives again who were on the receiving end of two chunks of the electorate's ire. On 7 November 1991, they lost Kincardine and Deeside to the Liberal Democrats and Langbaurgh in North Yorkshire to Labour.

And what happened at the general election six months later?

The Conservatives won them both back. The idea that by-elections can be a psephological quirk — and they can be — and exaggerate a party's popularity or otherwise, is what Tories cling to this weekend.

Boris Johnson told the BBC a "psychological transformation" in his character is "not going to happen"

But plenty of Boris Johnson's internal critics think the electorate's judgement on the prime minister's character is set and little can change that. His supporters hope his previous bounce-back-ability has at least one more boing in it.

Finally, then, to the DUP and the SNP. Northern Ireland's Democratic Unionists are refusing to go into devolved government at Stormont. They say they won't go back into power sharing until the part of the Brexit deal called the Northern Ireland Protocol is radically altered, removing that sense from many unionists that it was unpicking the stitches that hold the UK together, the overarching fear of their political creed.

On Monday, the proposed change in the law that could ditch chunks of the Protocol will be debated in the Commons.

Some are outraged at what they see as the government intentionally breaking international law.

Ministers insist it won't do that.

What we shouldn't expect is rapid movement from the DUP. They feel they've been repeatedly let down by Boris Johnson and they have a mandate to ensure they get the Protocol sorted, as they see it, before returning to Stormont.

Debating the Protocol Bill won't be enough to resolve that impasse.

And so to the Scottish National Party. The first thing which always bears repeating is how, 15 years into government at Holyrood, they continue to be the colossus of Scottish politics; everyone else a shrimp in comparison.

It doesn't insulate them from problems; their Westminster leader Ian Blackford has faced calls to resign over his party's handling of a sexual harassment complaint.

Ian Blackford apologises to victim and says Patrick Grady should "reflect" on behaviour

Not only has it raised questions about Mr Blackford's judgement in the eyes of his critics, but proven there is at least one mole within his ranks who has recorded and leaked what was meant to be a private meeting.

On Tuesday, party leader and Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon will set out how she plans to "unlock the door to another independence referendum", as one figure put it to me.

Exactly how they do that, with Boris Johnson refusing to countenance one, will be interesting.

It'll be a big moment at the core of the SNP's very reason for being - and so itself a mood-maker for them and Scottish politics more broadly.

- Published24 June 2022

- Published24 June 2022